The human body is a truly fascinating thing. Perhaps one of the most fascinating, and often the most talked about, is your core! We hear about our cores all the time—it’s borderline impossible to take a yoga class and not hear the teacher mention it or refer to it in some way. But have you ever stopped to think…

What exactly is my core?

I’m sure a few of you just answered that with “Easy! It’s your abs, obliques, & transverse abdominis!” You’re not wrong; that’s how many of us were traditionally trained in anatomy to think about the core musculature. But that abs-obliques-transverse logic is sadly bordering on prehistoric in our modern day. Many anatomists, kinesiologists, biomechanics, and physical medicine practitioners now interpret your core as so much more!

That’s exactly the gap I intend to fill with this series of articles about your core. I plan to take what you already know about anatomy and weave it together in a more holistic approach rather than follow older reductionist models. We’ll look at chains of muscles, or core subsystems, and how they relate to core principles of human movement (breathing, centralization, coordination, power, balance, stabilization, etc.)

There will be five different articles (including this one). Each one will focus on one core subsystem, its core principle, and how you can bring that into your practice or teaching. I will center each article on two poses: Deadbug & Birddog, as these are known to reinforce almost every aspect of each core subsystem & core principle. I’ll also include many other poses/exercises/concepts to bring into your practice, which will reinforce everything.

Let me make a quick note to keep in the back of your mind: The intent behind all of this is to discuss the interconnectivity of the body. There are many models and ways to describe what a core is and what its function is—I’m not trying to disprove them, nor am I trying to say that what I present to you here is the definitive version. What we want to avoid is a reductionist view of what is and is not our core.

Limiting the involved muscles to a select few or even to a few chains of muscles denies the true interconnected flowing nature of our tissues. All of these systems interweave together every moment to help us move and function. Fair warning that throughout these articles, I will be somewhat of a hypocrite by calling attention to select groups of muscles, but know that the intent is to view how all of these play with each other – knowledge of the parts grants one a more complete understanding of the whole.

Teacher note: Pay attention to the relationships of these muscles in their groups and chains. When it comes to sequencing, this is amazing knowledge to help you target specific areas and unlock new potentials in performance* and sensation in yoga asana.

*Yes, I know yoga is not about performance, especially physically. To be clear, I’m using the term performance to refer to your individual interpretation of success that you feel in any yoga pose. For example, one’s performance and success can range from sitting more comfortably in an easy or challenging posture to sticking and feeling strong in a very difficult posture.

Here’s the outline for this article:

- Core Anatomy & Biomechanics

- Intro: Core Principles & Core Subsystems

- “Breathing & Centralization” Deep Anterior Line

- “Cross Connections & Coordination” Anterior & Posterior Oblique Slings

- “Power & Propulsion” Deep Longitudinal

- “Balance & Stabilization” Lateral Sling Subsystem

- Essential Core Poses: Deadbug & Birddog

- Pitfalls of Traditional Core

Let’s start with an introduction to your core!

Core Anatomy & Biomechanics

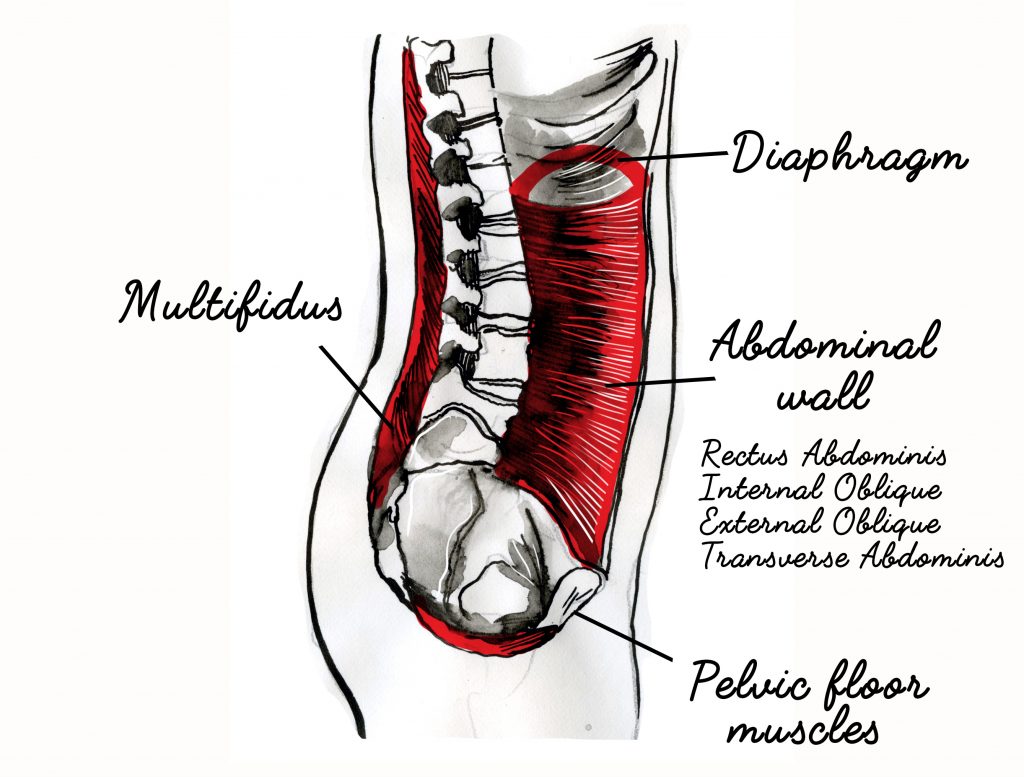

This is your core. It resembles a cylinder and is the powerhouse center of your body. I like to describe it as a room: Ceiling – Diaphragm, Floor – Pelvic Floor, Walls – Abdominal Wall (including traverse abdominis) & Multifidi.

The muscles of your Core cylinder work as a functional unit to provide stabilization to your spine.

- Stabilization of your spine is necessary for safe, purposeful movement of your extremities and head.

- These muscles automatically fire prior to purposeful movement to establish a stable base. This is known in kinesiology as a “Feed Forward Mechanism.”

The integrity of these muscles is a huge factor in the amount of stability and power they can unlock in your body. Now, image your core as a soda can. If you were to step on the can, it would be potentially strong enough to support your weight—without any dents. But if there is a dent anywhere along the can, it will collapse under even a minuscule amount of pressure!

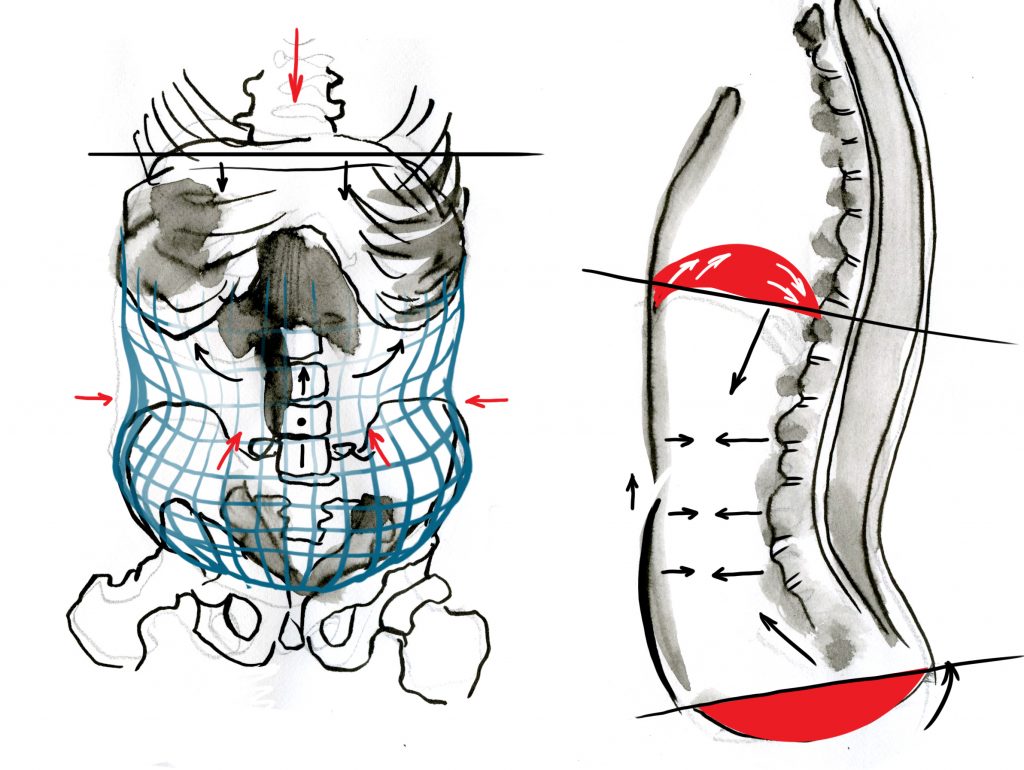

A fancy kinesiology term for your core cylinder is “Sagittal Stabilization.” This refers to the stabilization of our trunk in the sagittal plane, which is the plane that divides our body between right and left. In movement, the sagittal plane can refer to both forward active movements (running, crawling, lunging) or more fixed stationary movements like squatting and tilting of the pelvis (forward or back).

We first create sagittal stabilization when we are about three months old. Around this milestone in our development, our diaphragm starts to play a stronger role in our posture and through the cultivation of sagittal stabilization and intra-abdominal air pressure (IAP), we can begin to crawl & walk! I’ll discuss this more in the next article when we talk about breathing.

In addition to stabilizing your spine for movement, these muscles are also very intimately connected to your breathing!

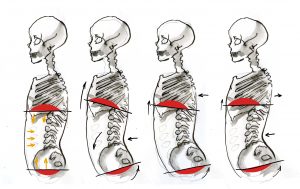

You can see in this illustration how the diaphragm and pelvic floor move together with your breath. Plus, it shows how your abdominal wall expands as you inhale and deflates as you exhale.

We call this movement of air in your abdomen IAP or Intra-abdominal Air Pressure. IAP is the integration of your breathing with the aforementioned core integrity. Remember the analogy of the soda can? IAP would be the air pressure in the can actively pressing against its walls to create integrity and keep it from buckling.

Exercise: Breathing & Establishing IAP

- Supine: Collapsed Bridge Abdominal Wall Breathing

- Prone: Sleeping Cactus “Alligator Breathing”

Barrel Breathing (360 deg breathing)

On your inhale you should feel:

- Expansion of your entire abdomen, like a ring or band, is around your belly button

- Your lower lateral (outer) ribs expand outwards

- Some expansion outward in your lower back (more subtle than the others)

Pitfall: Many people breathe solely with their abs (rectus abdominis) and miss out on the lateral (side body) and posterior (back body) components of breathing!

I’ll discuss breathing and its relationship to other muscles in your body in more detail in article #2 about the deep anterior line subsystem.

Introduction to Your Core Subsystems:

To best understand the versatility and functions of your core, I’ll be breaking it down to fourmain functional units of muscles. There are many ways to view one’s core and understand both its function and anatomy. While I don’t completely subscribe to the anatomy trains model*, I believe that looking at the function of these muscle chains helps to foster a baseline understanding of the core principles that are essential to human movement.

*Looking at the human body in chains of muscles is just one approach. As with almost any model, it has its pros and cons. I, personally, like to use muscle chains to discuss anatomy—especially to students that may not have a lot of experience with or knowledge of anatomy. When you delve deeper into anatomy and biomechanics looking at the body in muscular chains leads one to a more reductionist view on human anatomy and function. The human body as a whole doesn’t necessarily move or function within the model of muscular chains. It is much more complicated than what I’ll be presenting in this article or really for any single model to describe. We do have to start somewhere with a baseline of anatomy. My hope is that by reducing, simplifying, and looking at the parts we can reach a common understanding and have a better glimpse at understanding the larger whole.

#1 Deep Anterior Line – Breathing & Centralization

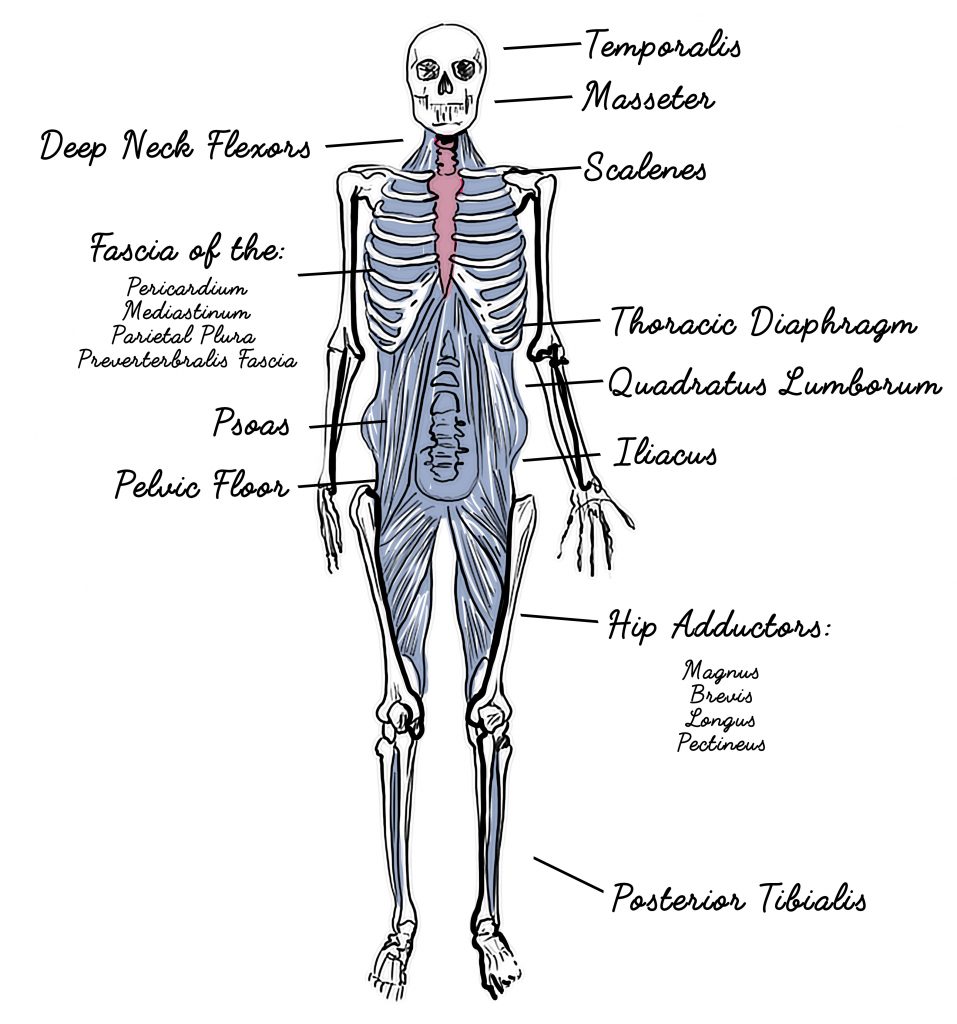

Also referred to as your “deep core,” your deep anterior line connects your legs and inner thighs all the way up to your jaw! It houses a lot of the muscles of breathing, including your transverse abdominis (not shown). It also plays a major role in how we stabilize our spine.

Subsystem #2: Anterior & Posterior Oblique Slings – Cross Connections & Coordination

Your oblique slings are functional units of muscle that connect your leg to the opposite arm. It’s through this system of rotating we derive a lot of our rotational power, which enables us to walk and run. It’s also how we coordinate a lot of our movement in our upper and lower body.

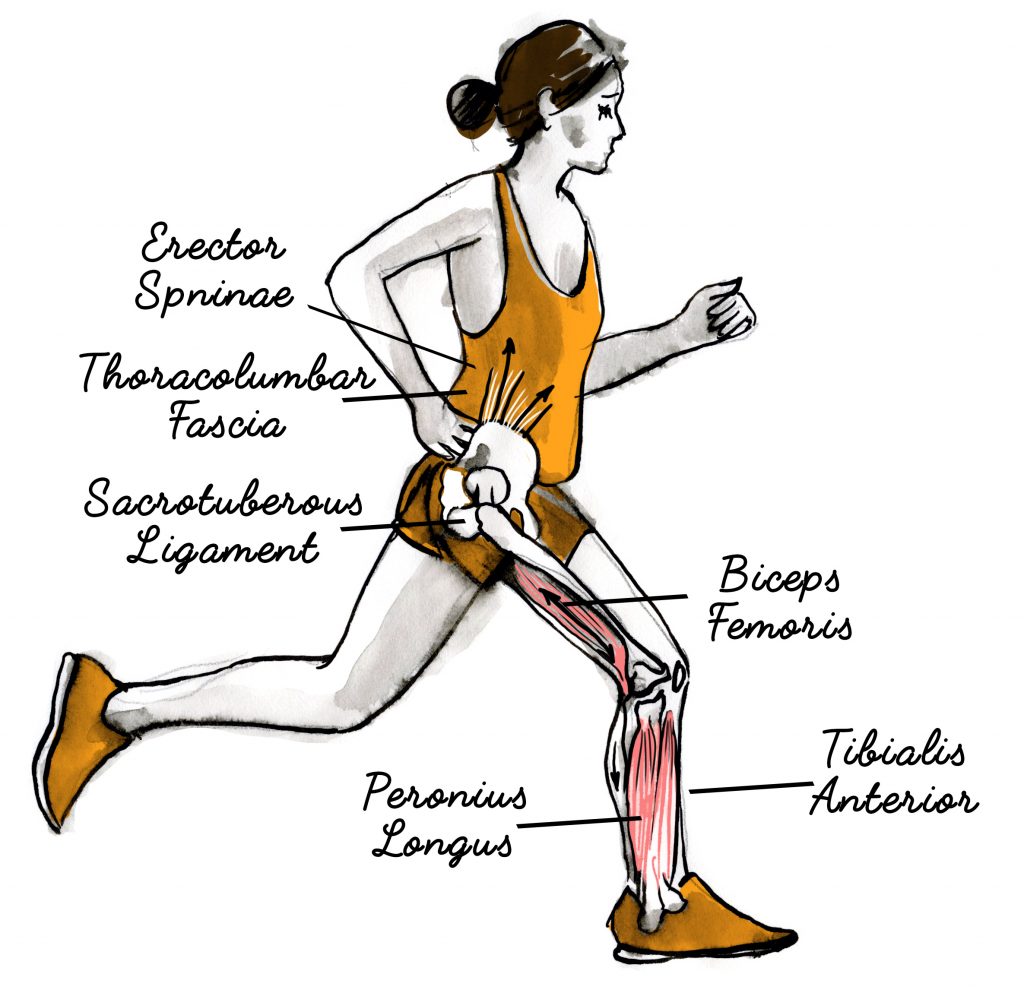

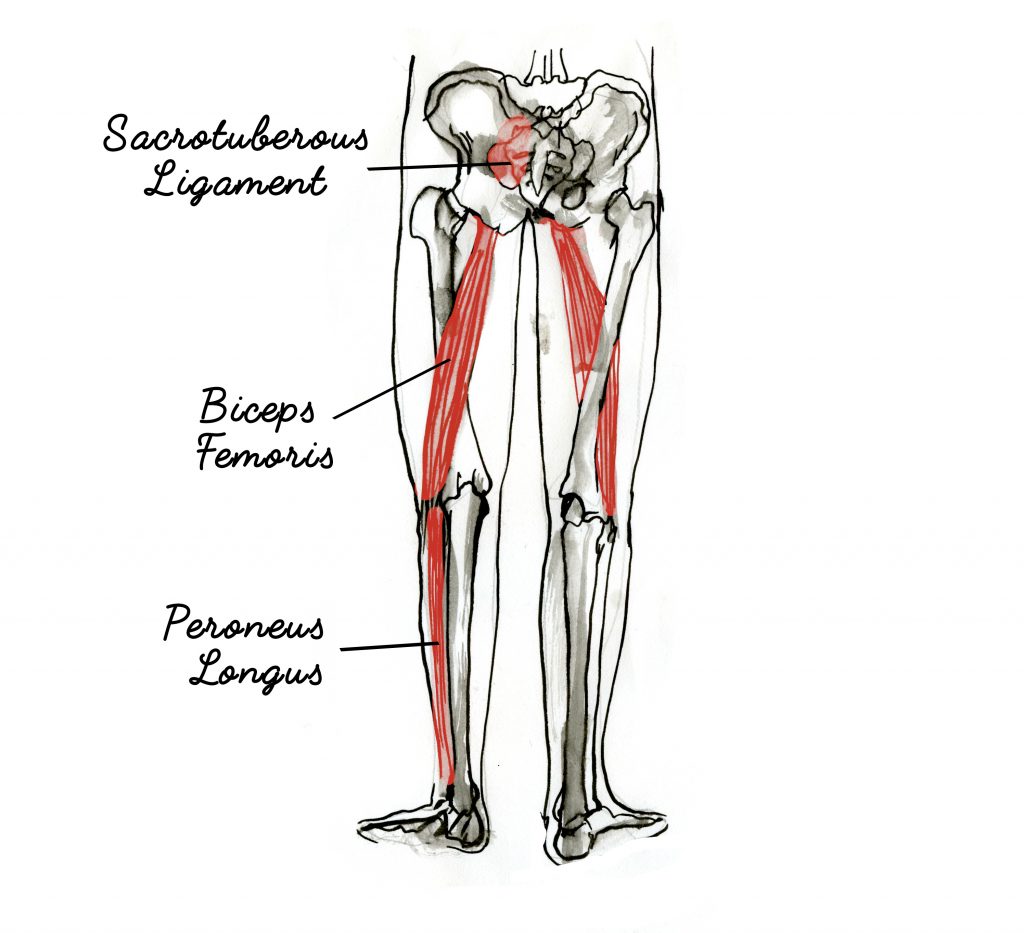

Subsystem #3: Deep Longitudinal Line – Power & Propulsion

The deep longitudinal line is a functional unit of muscles that helps propel us off the ground when we walk or run. It also helps stabilize our sacrum and spine in relation to our legs and feet. The sacrotuberous ligament is a part of this line and is responsible for transferring force from the legs up to the spine via the spinal erectors.

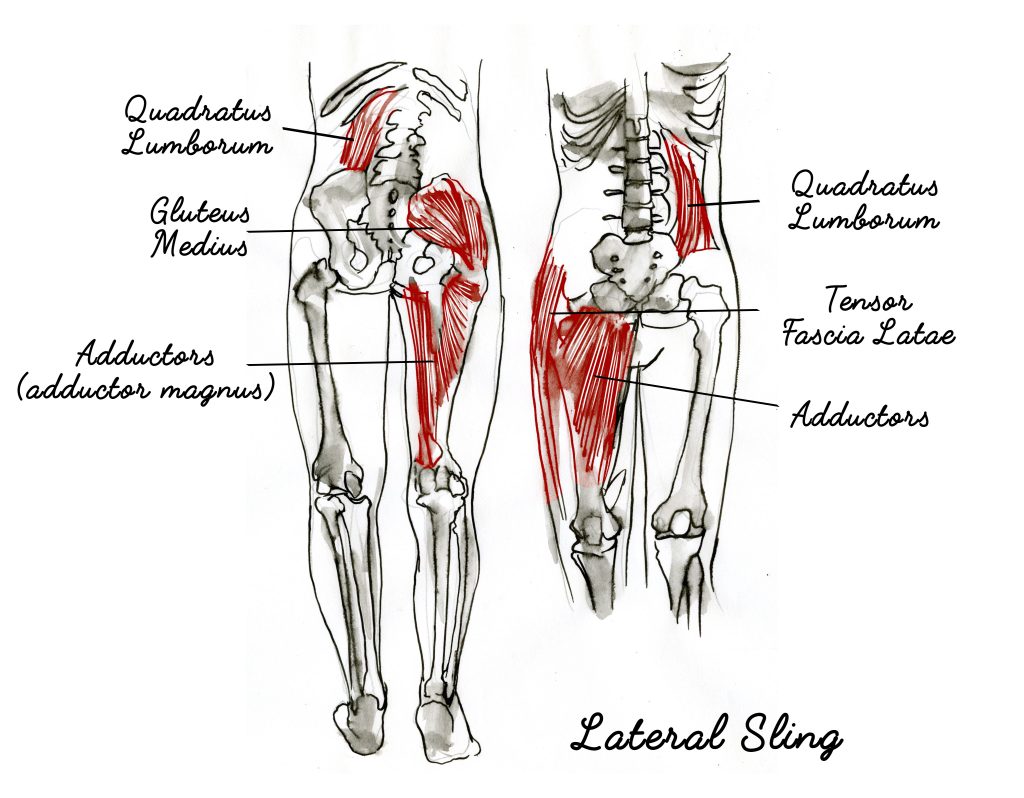

Subsystem #4: Lateral Subsystem – Balance & Stabilization

The lateral sling subsystem is made up of functional muscle groups that help stabilize your hip, pelvis, and spine and is largely responsible for helping us balance. Your QL works to stabilize your pelvis, ribs, and spine with your opposite glute medius, TFL, and adductor group stabilizing your pelvis and femur.

Essential Core: Deadbug & Birddog

Deadbug and its movement cousin Birddog are very commonly used in the kinesiology world as basic core exercises. I sometimes see them in Yoga with different names, but to keep things simple and to also bring some clarity to the postures, I’ll use their kinesio names.

I believe these are important postures for yoga teachers to understand because a lot of yoga teachers still think crunches constitute viable core training—it turns out crunches are not all that great for you, nor do they teach proper engagement and strength when it comes to the core musculature.

Crunches = Junk Food Movement

Katy Bowman uses the term “Junk Food Movement” to describe movement without purpose/function/connection and crunches are the embodiment of that:

- Crunches lack engagement of the target muscle (rectus abdominis). Lower back Guru Dr. Stuart Mcgill says that crunches recruit less than 20% of the rectus abdominis! Most of your effort is in your hip flexors instead.

- Crunches often lack an eccentric (lengthening) phase. Unless you have a physioball, most crunches are performed from neutral to concentric (short). The eccentric phase is important for muscle strength, as that’s when the muscle builds and stores energy for contraction.

- Crunches can impair breathing! Over-tensioning the rectus abdominis and hip flexors can create a dysfunctional ab breath instead of a good 360-degree abdominal wall breath. Crunches impose a lot of tension in the position those muscles are already in when we sit all day!

- Crunches can also impose a lot of strain in our lower back and spinal discs. Without proper back strength, which a lot of people lack in this modern age, there’s often an imbalance between your trunk flexors (abs, hip flexors, etc.) being too dominant over your trunk extensors (erectors, lats, glutes, etc.).

****I will note that not all crunches are created equal. These problems refer to a general hands behind the ears, keep your feet planted, exhale lift, inhale lower crunch. There are viable and sustainable ways to crunch (such as the Janda Crunch, McGill Sit Up, etc.) that I will discuss later. For now, feel free to practice Svadhyaya and look those crunches up on Google/Youtube.

Practice Core with Integrity

A safe and sustainable alternative is Deadbug & Birddog because they reinforce all of the Core Subsystems I listed above as well as a lot of the principles of Balance, Stabilization, and Coordination. Each subsequent article will introduce different aspects of alignment, and also different modifications to each of these. These two poses are a staple in my own classes, and I hope after this they become a large part of your own as they have a lot of great benefits, are accessible to most, and each has a few variations you can play with!

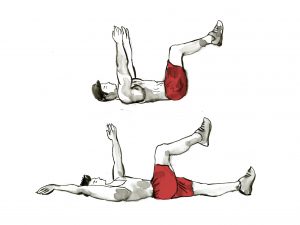

Deadbug

Start: Lying with your back on the floor extend your arms and legs to the sky (illustration above)

Step 1: Moving single parts

- Start by moving 1 limb at a time. Ex: R arm overhead, return. L arm overhead, return. R leg extends, return. Etc.

Step 2: Moving contralateral (opposite) parts

- Go slow! This coordination may be harder than it seems.

- Reach your right arm overhead, and extend your left leg, return and switch.

Adding Breathing:

- Inhale, reach – exhale, return.

*I like to tell students there are 2 main rules:

- You will always have 1 arm and 1 leg not moving in the sky at all times.

- You are always reaching away from your abdomen.

**Common Flaws:

- Moving your arm towards your leg—remember it should be moving overhead.

- Moving the same side arm & leg.

- Not keeping an arm & leg still in the air.

A lot of these issues come from a lack of body awareness and also a tendency to go really fast. My best advice is to start slow with the individual parts (Step 1) to let people understand R and L and upper and lower extremities. Then introduce the opposite arm and leg movements. If someone loses their coordination, remind them to slow down and if needed go back to working on the single limb movement.

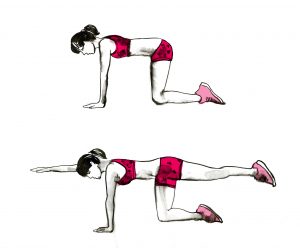

Birddog

*Note: I often see this pose taught as a Table Top crunch. In a good Birddog, she is NOT crunching! She’s extending first, and the crunch part is actually an advanced layer usually introduced once one can maintain good hip & spinal alignment with extension.

Start: Quadruped – hands placed comfortably under shoulders, knees placed under hips

Step 1: Learning to Extend

- Like the Deadbug try to just reach 1 arm up – thumb up – then place it down. Continue with alternating and lifting one leg at a time. (illustration above)

Step 2: Holding Extension

- Lift one arm up and then the opposite leg (ex: R arm, L leg).

- Hold and attempt to maintain the lift through your hand and your heel

*The first 2 steps are to teach people how to maintain core stability with moving parts. Adding Step 3 requires 2 key components: the ability to prevent movement in the spine & the ability to keep shoulders and hips stacked above your wrists and knees.

- Preventing spinal motion: There is a tendency to add a cat/cow like motion to a Birddog. While this is not wrong—it is not the intent of the exercise I am demonstrating to you. The intent is to maintain spinal stability and avoid any spinal movement while your limbs move.

- Stacking Shoulders & Hips: Another common tendency is to see especially the pelvis sway side to side. In these instances, you can likely observe the hip moving outside the knee to compensate for a lack of hip extension (lifting your leg). Part of maintaining spinal stiffness & stability is also minimizing the amount of sway of your pelvis and shoulders. Just your arm and leg move—nothing else.

- In this instance, many people tend to externally rotate their leg when they lift. Because hip extension is a movement many people need to work on, the glutes will overcompensate by rotating the leg to help lift it. Your toes should be pointing towards the ground throughout the entire exercise.

Step 3: Adding On

- If you can maintain good spinal stability, then you can try bending your elbow into your chest and bringing your knee into your abdomen.

- This “knee to elbow” crunchy move is common in yoga but you lose core/spinal stability if you allow your spine to cat/cow. Again, not wrong to cat/cow but if your intent aligns with cultivating spinal stability, try to NOT move your spine but bend and move your limbs.

Flaws:

- Aside from what I mentioned earlier, the biggest flaw I see with Birddog is people jumping into step 3 without any semblance of spinal stability, which is the exact intent of steps 1 & 2. You can go ahead and cat/cow and sway all you want but it is a VASTLY different experience if you attempt to keep your spine still and work more on disassociating your arms and legs.

Part I Summary:

- Your core resembles a cylinder.

- Roof – Diaphragm

- Floor – Pelvic Floor

- Walls – Abdominal Wall & Multifidi

- The purpose of your core is to provide spinal stabilization before any purposeful movement.

- Breathing is also an important factor, as it’s your IAP that helps establish your core stability.

- Inhales should expand our abdominal wall 360 degrees around our abdomen.

- You have 4 major functional groups of muscles that contribute to your core stability & balance:

- Deep anterior

- Oblique slings

- Deep longitudinal

- Lateral sling

- Traditional core poses & exercises, like crunches, often neglect purpose, function, or connection.

- Deadbug & Birddog implement each of the core subsystems and their core principles and make great additions to your yoga practice.

Conclusion:

That’s all for part I. Learning about your core starts with the cylinder and how it creates spinal stability in addition to how interconnected your breathing is with your core. Start practicing your Barrel Breath and focus on the expansion of your lower abdominal wall & backbody. Then integrate in your IAP and see if you can move while inhaling to expand, and exhaling to maintain the integrity of your abdominal wall brace!

This isn’t an easy concept, but with diligent effort comes mastery! Once you get a good hold of your IAP and core stabilization you’ll be amazed at what your body is capable of and how different it feels moving your body through traditional postures.

In the next article, we’ll take a deeper look at breathing and the concept of centralizing as we create a better understanding of our Deep Anterior Line Subsystem. There will be a bunch about the importance of your hip adductors, and some cool knowledge bombs about your jaw, too!

Until then,

Dr. G

Edited by Jaimee Hoefert

Illustrations by Ksenia Sapunkova | kseniasapunkova.com