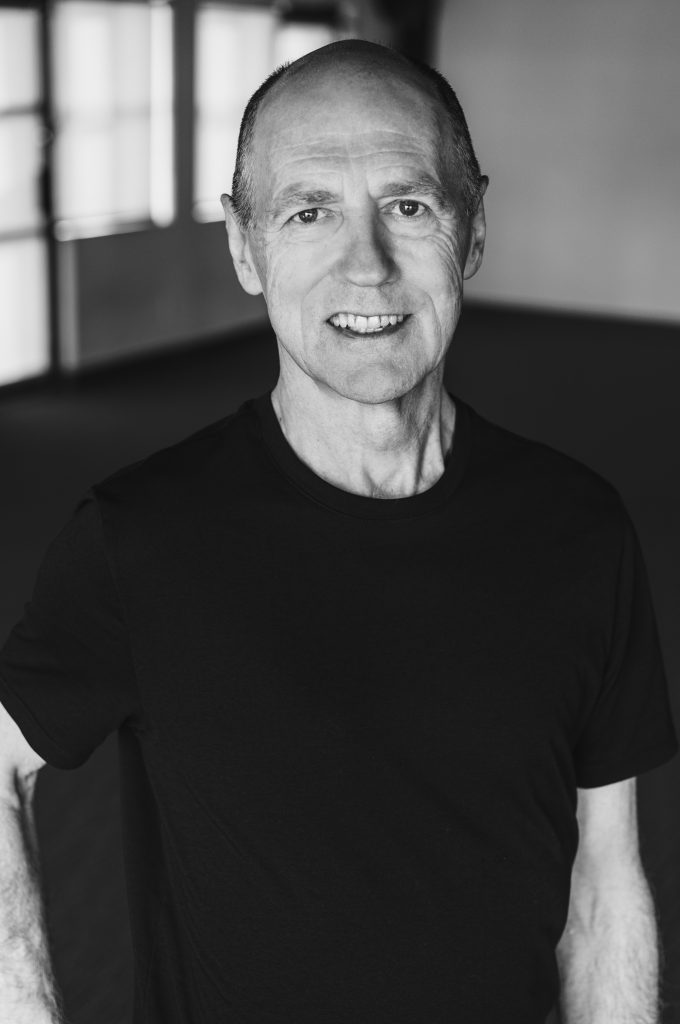

Bernie Clark’s material has been an essential resource for me as a Yoga Instructor for over a decade. On top of teaching yoga & meditation since 1998, Bernie is the author of several books and the creator of www.YinYoga.com. He is gifted in merging historic practices and ancient teachings with conventional wisdom and modern science. The first of his books I ever read was “Yinsights” – A Journey into the Philosophy & Practice of Yin Yoga. As a new teacher, this book played an integral part in getting my feet under me. Something that stood out to me was his statement:

“Having a good teacher who can interpret the teachings and intentions of the gurus of the ages and bring the teachings to us in a modern manner is invaluable”

(YinSights, P.244)

For many, including myself, Bernie Clark has become this teacher. Inspired by Paul Grilley, Bernie’s latest books recognize the complexity and variation within the human shape and form, bringing to light the responsibility of the modern day Yoga instructor to acknowledge this variation. Each student experiences their body and their practice in their own unique way, and it’s imperative to consider the implications of this on student-teacher interaction and the outcomes of the practice.

In his latest books, Bernie Clark breaks down the HOW & WHY of human variation in the physical body. With clear examples, contemporary science, and anatomical detail, he has created brilliant resources for the evolution of yoga and movement practices.

His books provide great insight and perspective on how teachers can help students develop a general understanding of the key functions of their body and the meaning behind their movement. Bernie demonstrates that through clarity and intention, we can help students learn to sense their way into optimal, healthy alignment on the mat and in everything they do.

It was an absolute honour to interview him about his two latest books:

“YOUR BODY, YOUR YOGA”

&

“YOUR SPINE, YOUR YOGA”

Read on to hear more of Bernie’s personal thoughts and insights on the project!

What inspired this project? What inspired you to write this series of books?

My inspiration is Paul Grilley. He’s been teaching the reality and implications of human variations for decades. It’s so important for yoga teachers and their students to understand why some postures will not work for them and why not everyone can do every pose. I would often ask him to write a book about it (he does have a great DVD on the topic called Anatomy for Yoga), but he kept saying “no, you can write it!” So, eventually, I did! However, as I started to plan out the book, I realized one reason Paul didn’t want to do this… It’s a big project. I realized that to do it properly would take a series of books, not just one. I am 2/3rds of the way through — still one more book to come (looking at the Upper Body).

Do you think we can safely and accurately address the individual needs of each student in the current model of public, drop-in hatha yoga classes? Or is a paradigm shift needed in how we share the teachings of yoga to maximize potential outcomes and benefits for the students?

Yes, it definitely is possible to teach a functional approach to yoga even to students in a drop-in class. While the aesthetic approach is easier to share (that is, arranging students’ bodies to all look the same), the functional approach does require greater teaching skill. But most of the work is done when the teacher teaches the students how to feel her own ideal or functional alignment. It is a paradigm shift, as you say, but one that is already taking place.

Most of the work is done when the teacher teaches the students how to feel her own ideal or functional alignment

Are some principles of alignment and specific guidelines less essential in a practice that involves more movement and less time spent in each individual pose? (For example, a Vinyasa Flow class vs. a Yin class?)

Once the student becomes her own teacher and can evaluate whether a movement or posture is safe or dangerous for her, this skill can be applied in all styles of yoga. She must first be taught to pay attention, and then become aware of her intentions. This is above and beyond any principles of alignment; alignment follows after intention and attention. So, I would say that intention and attention are essential in all styles of yoga practice, and individual alignment and movement techniques will flow effortlessly from there. Both Vinyasa and Yin classes need to be done with intention and attention, and a focus on personal alignment will naturally develop.

Intention and attention are essential in all styles of yoga practice, and individual alignment and movement techniques will flow effortlessly from there

Is the reality in human variation and diversity related to why you have dedicated your efforts to teaching Yin Yoga?

No, my interest in Yin Yoga developed out of a need to balance my overly active (yang) yoga practices at the time and my very yang-lifestyle. Realizing the importance of understanding human variation and knowing what stops me when I feel stuck (tension or compression), was not Yin Yoga related, but all yoga related. One does not need to be a Yin Yoga teacher or yin-enthusiast to appreciate the implications of human variation. Human variation is important in all branches of therapy: yoga, medicine, psychotherapy, spirituality, etc. We are unique: what works for someone else may not be good for us.

Human variation is important in all branches of therapy: yoga, medicine, psychotherapy, spirituality, etc. We are unique: what works for someone else may not be good for us.

It seems an overlying theme or principal in your work is that our role as teachers is to help students learn to pay attention; to sense and understand the feedback from their body and navigate their way to healthy alignment and mobility. I agree wholeheartedly! Do you find this challenging with beginner students who are looking to you for “the answer” or how to “do it right”? How do you approach this?

This is very challenging for students and teachers. Even very flexible students, who seem to have an “advanced” yoga practice, may possess very little inner awareness. This isn’t surprising because in our culture, we don’t value introspection or interoception. We are taught to mask inner feeling: think of all the ways our society turns us away from uncomfortable inner experiences — pain killers, drugs, alcohol, binge-eating, binge-watching Netflix, etc.

When the teacher first asks a student, “What are you feeling?”, the student has no idea. The teacher has to guide her. But in time, this skill can be developed so that the student becomes her own guide. The teacher who tells students how they should look in a pose is depriving the students of learning how they should be in a pose. I would rather put this responsibility on to the student. As a teacher, I have no idea what you are feeling or what is safe for you. But, perhaps I can help figure this out for yourself.

Does the body-awareness and understanding of sensation that we’re trying to cultivate in our students require a certain amount of engagement in the practice? In other words, it’s not something that we can “give” our students, but something they must feel and come to on their own. Do you think it could be helpful for students to feel an incorrect alignment to a certain extent, so they can feel their way to balance and stability?

Doing something the wrong way can be instructive: that is how most teenagers learn. They don’t want to follow their parent’s sage advice, so they make their own mistakes (the same ones the parents made). This is why older people are considered wiser: they’ve had more time to make mistakes. But this is not the best way to learn: it’s a painful process to always learn through mistakes.

A good teacher can guide the student’s awareness. It starts with simple questions: “What are you feeling? Where? Is the most obvious sensation deep or shallow? Is it warm or cool? Is it throbbing or constant?” In Your Body, Your Yoga are a series of questions teachers can have students ask of themselves, depending upon the targeted tissues we are trying to affect. There’s also a listing of typical pain responses if the poses are too deep. It’s important to help students recognize when they have gone too far.

What would you say to someone who has been teaching or practicing yoga for many years, and feels completely disheartened and overwhelmed by this information on human variability?

You are not alone! Student doctors go through the same feeling of being overwhelmed. It would be nice if we were all the same and one pill would cure everybody of every disease. But this is not reality. However, rather than be disheartened by the vast range of human variations, understand that it’s not necessary to know all the variations! No one can know all that, and you don’t have to anyway. All you have to do is help each student learn her own body. If you can teach each student to fly her own plane, then you don’t have to be up there in the cockpit with them. You’re simply ground control giving advice once in a while, while they are fully responsible for their flight, which is their life!

I really love two key assertions that you made in “Your Body, Your Yoga” 1) Who is flying the airplane; 2) Be cautious of creating alignment cues based on only your own experience. Can you briefly elaborate on each of these, and how it shifts the perspective of the teacher, and their relationship to the students’ practice?

1) This analogy of “flying your own plane” basically means that everyone in your life who wants to help you are on the ground. They are not on the plane with you. If you crash, you suffer — they are still safe. So you have to take responsibility and take control. Ground control is full of helpful advisors: your doctor, dentist, accountant, lawyer, yoga teacher… They want to help, but you’re the one flying the plane. Don’t give up your authority to an expert no matter how much he knows. Check everything out and see if it works for you. (The Buddha pretty much said the same thing 2,500 years ago when he said, “Put no head above your own”.) This also takes a big burden off the teacher! The teacher is not responsible for flying the plane, but for giving flying lessons to her student. Teachers: do not try to take control of the plane! Let them do the flying.

2) The second point is a natural reaction for all teachers. I used to do this too! I would do something in my own practice that worked really well, and then shared it with my students. Then, I was puzzled why some students couldn’t do what I was doing. I was ignorant of human variations and thought they were just not listening or not trying. I didn’t understand that they were, but their bodies were just different from mine, and they couldn’t do what I wanted them to do. What I should have been focussed on was the intention of the pose, not the position their body was in. Is their posture creating a safe stress in the targeted areas? If so, leave them alone! If not, adjust and find the version of the pose that does work for them (which means it does create the desired stress in the targeted areas).

Do you find that students are receptive to understanding the “What stops me”* spectrum, the difference between tension and compression, and the descriptors of sensation? Do you think it requires a certain amount of practice to create a deeper understanding of these concepts?

(*When students feel stuck or limited in a posture, you encourage them to inquire: ‘What stops me?’ When you ask them to consider the variety of factors that could be creating limitation, are they receptive? Do students understand the difference between tension and compression, and the descriptors of sensation? Do you think it requires a certain amount of practice to create a deeper understanding of these concepts?)

I think students can understand this very quickly. The concepts are simple to grasp. However, some students have been so strongly influenced by other teachers that they may rebel. They believe they already know the “proper” way to do a particular pose, and don’t want to explore other options. All we can do is offer these newer ways to explore the body and if it resonates with the student, great! If not, well, they are flying their plane. I am only an advisor. As the old saying goes, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it do triangle pose.”

In “Your Spine, Your Yoga,” you bring light to the function of the spine, and the importance of respecting its natural, neutral alignment. In your discussion on posture, you mentioned that “Good posture could be defined as where the body expends the least amount of energy to remain balanced,” and also that “the line of gravity has to shift to accommodate the reality of the body.” Do you think it’s important to find this posture of ease & alignment in Tadasana before moving to more complicated postures?

Yes. It’s much easier to learn where your hips and spine are when you are in a simple posture, like Tadasana (mountain pose) than in the more complex poses like Warrior or Triangle. Start simple, learn what it feels like to be there, and then challenge yourself more deeply.

You speak about the importance of counter-poses to create balance and restore equilibrium. Do you think it’s important to move the spine in all directions to create a full-spectrum practice? For example, flexion/extension, lateral bends, and twists?

Definitely! The spine is designed to move in all directions, so in every class, I like to mobilize it in all these directions. There are only 6, so it need not take much time. But, remember, the primary function of the spine is stability. It is more important to build endurance and strength in the spine than in enhancing flexibility.

The primary function of the spine is stability. It is more important to build endurance and strength in the spine than in enhancing flexibility

For individuals who have pain or immobility in one of the SI joints, is it beneficial to allow the pelvis to move a little with the spine? For example, in twists or forward folds, allowing the pelvis to move rather than moving the spine against a fixed pelvis?

To say that the student with SI joint pain or immobility should avoid separately moving the pelvis and the spine is a prescription that I would not be comfortable making. I would first ask such a student what her doctor says. Any prescription should be given with an understanding of the cause of the problem. Unfortunately, there are many potential causes of SI pain and most of these are unrelated to the joint itself. Avoiding stress in the joint out of fear of pain may actually worsen the condition. A yoga therapist may work with this student to determine the cause of the pain, and then come up with proscribed and prescribed movements.

I think yoga teachers become too cautious at times: even injured areas need some stress! Not too much, of course, but to claim that a student with pain should avoid various movements may be counterproductive. Beware of dogmatic prescriptions: the student is unique. Find out what is causing her problem first and then jointly develop a path forward.

You draw awareness to the importance of spinal stability before mobility, and define stable as: “steady, firm, enduring and resistant to sudden change, but functionally able to adjust to movement.” Do you think we have a responsibility as teachers to facilitate an understanding of what stability feels like in the spine before we instruct postures that require more spinal movement? What would this look like in terms of sequencing?

Yes! First and foremost, the spine is designed for stability. We should be teaching students how to stabilize the spine and develop endurance before looking to increase range of motion. There is no health benefits to the big spine movements taught in many yoga classes. Wheel pose, as one example, takes a spine way beyond its normal functional range of motion — we don’t need that much mobility! We need enough to live our daily lives and play our sports, but the only reason for a big, bendy spine is to look good in yoga poses. That can be fine, especially if you are a dancer or gymnast, but if your intention is to have a healthy, functional spine that will last you a lifetime, there is no need for such large ranges of motions.

First and foremost, the spine is designed for stability. We should be teaching students how to stabilize the spine and develop endurance before looking to increase range of motion.

If you insist on offering big, bendy spine poses in your yoga classes, start with shallower movements to loosen up the areas, and then while doing the big bendy pose, reduce as much load on the spine as possible. After doing the bendy poses, stiffen the spine up again with strength building exercises.

In “Your Spine, Your Yoga,” you mention being clear about the intention of the pose and asking: “Is the maximum range of motion really necessary, or is it only an aesthetic goal?” Are there circumstances or intentions for the practice (other than the aesthetic of the pose) that would prioritize maximum range of motion?

I can’t think of any. Why do we want huge ranges of motion? We need enough to be able to function well in our life, our work, our sports. These activities do not require huge ranges of motion. Health requires a balance between mobility, stability, and endurance. When we are targeting the spine, unless you are very limited in its range of motion, the priorities should be endurance, then strength, and then mobility.

If there was one key point, or take-away, from each book, what would that be?

You are unique! What you need to optimize your well-being is also unique. This simple understanding will affect how you practice your yoga. In Your Body, Your Yoga the implications of this simple fact is investigated for the lower body: the hips, knees, ankles, and feet. In Your Spine, Your Yoga the investigation continues for the axial body: the pelvis, sacrum, lumbar, thoracic and cervical spine.

You can learn more about Bernie Clark and his books at yinyoga.com. Your Body, Your Yoga & Your Spine, Your Yoga are both available in print or e-book through Amazon or Barnes & Noble. Stay tuned for the third book in this series that will focus on the upper body and other aspects of human variation that have not yet been addressed!

Edited by Ely Bakouche

Enjoyed reading this article? Consider supporting us on Patreon or making a one-time donation. As little as $2 will allow us to publish many more amazing articles about yoga and mindfulness.