This article is meant to be the beginning of a broader inquiry into the role of the yoga teacher in today’s society from a historical, theoretical, cultural, and practical perspective. This inquiry started with my own frustration and curiosity as I looked into the future and considered what my career as a full-time independent yoga teacher could look like.

After teaching yoga full-time for over three years now, with no lack of passion for the practice or opportunities to share, I still feel like the future is daunting, and at the very least unsustainable, as I look for ways to grow my business.

I have no interest in owning a yoga studio. This seems to have been the preferred path for many yoga teachers in the past decade or so who wanted to make yoga a full-time career. As a result, there are now several markets in the US where it is entirely possible to be an independent yoga teacher and have enough opportunities to teach group classes, privates, and workshops while sustaining a full-time income. However, this includes taking on the very real potential for burnout and exhaustion.

I also have no need to be a “yogalebrity”. Even if I had wanted to the age of the yogalebrity seems to be in its sunset phase — a passing trend that lasted for all of about 15 years concurrently with the rise of yoga coming into the mainstream of American culture.

That left me wondering, where do I go next? In other industries, you might expect to be promoted to a new job title with new responsibilities after a few years in one role. Even as a small business owner or entrepreneur, you’re always looking for new ways to grow and expand.

Naturally, as anyone in any industry would, I looked to my peers and colleagues for models that would inspire and motivate me to continue to grow in my career as a full-time independent yoga teacher. I found there weren’t many readily available examples out there to study and learn from. I decided to look to the past to see if I could figure out how teaching yoga has evolved. We learn plenty about the “history of yoga” in teacher training, but what about the history of the yoga teacher?

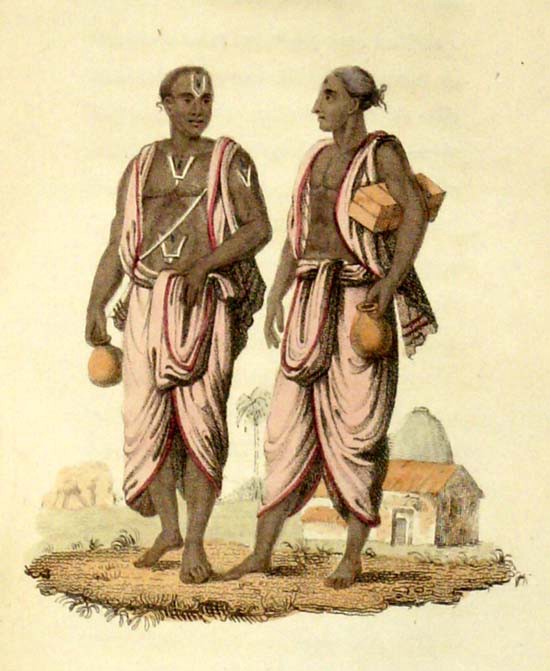

In the beginning, there were the Brahmins

Ancient Indian texts such as the Mahabharata, feature many characters from the Brahmin class of the caste system who were responsible for carrying forth the teachings of ancient spiritual traditions. Throughout history, these teachers have been instrumental in keeping these spiritual traditions alive and relevant.

Sidenote: Currently, some academics argue that yoga did not develop from the Vedic tradition, but rather outside the Vedic tradition. As such, it was the Brahmins of the Vedic tradition who borrowed some of what the Sramanas (ascetic strivers) developed and called it yoga. Scholars also tend to view yoga as a multiplicity rather than a single entity and recognize that yoga has had many forms and origins, leaving the Western rational mind perplexed when trying to pinpoint where yoga all began. Regardless of when or where yoga originally developed and who is responsible for its creation, what is known is that the Brahmins “popularized” yoga and brought it out of the forest into the “mainstream” thousands of years ago.

The Wikipedia entry for “Brahmin” defines this category of the caste system as the “priests, teachers, and protectors of sacred learning across generations.” In the caste system, Brahmins are at the very top of the pyramid – the most revered, important, and powerful. In fact, it was the duty of the Kshatriya, or warrior class, to protect the Brahmins, as is described extensively in the Mahabharata.

Ideally, the entire social hierarchy in India was set up to ensure that teachers never had to worry about paying rent and could spend all their time focused on their studies, sharing what they learned, and mentoring others. (Ha!)

Unfortunately, much of this version of the Indian world order is confined to fiction or unverifiable Sanskrit histories that blur the boundary between reality and myth, according to historians and scholars. In reality, it’s more likely that those of the Brahmin class held other occupations such as farmer, merchant, warrior, and other regular-joe jobs to survive. (Hmmm…)

The practicalities of being a Brahmin back in the day

According to the Dharmasutras, written sometime in the 1st millennium BCE as a guideline for how to live in society, explain that Brahmins, “may impart Vedic instructions to a teacher, relative, friend, elder, anyone who offers exchange of knowledge he wants, or anyone who pays for such education.”

Sharing of knowledge was viewed as an exchange of energy even in the 1st century BCE!

However, this same Dharmasutra text goes on to permit and encourage Brahmins to take on other occupations to sustain themselves, including agriculture, trade, money lending (on interest!) and what would today be considered military service. The only forbidden occupations specified in the text included “engaging in the trade of animals for slaughter, meat, medicines and milk products…” In addition, Brahmins were banned from trading “human beings, meat, skins, weapons, barren cows, sesame seeds, pepper, and merits.”

A similar and updated text, “The Dharmashastras”, written in the 1st millennium CE, when referring to the Brahmin status stated: “He should gather wealth just sufficient for his subsistence through irreproachable activities that are specific to him, without fatiguing his body [emphasis added].”

This last part is of particular interest and interpretation to the modern yoga teacher.

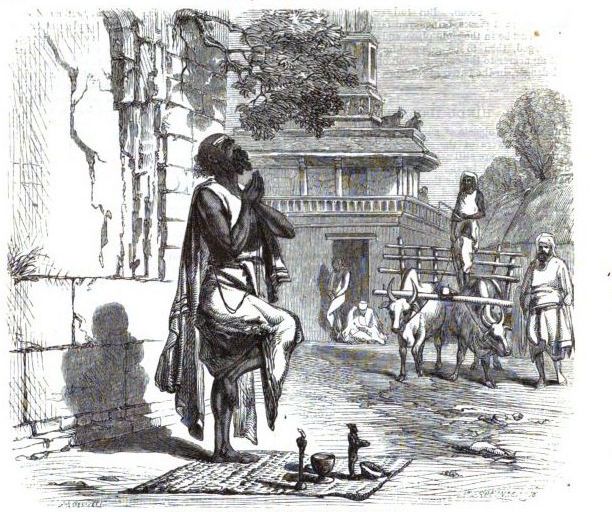

Yoga’s foothold outside of mainstream society

Even though the wisdom holders began as Brahmins in the caste system, much of yoga developed outside the caste system and mainstream society. This independence from governing and religious bodies and a focus on individual growth allowed yoga to blossom outside of the politics of the day but also situated the practice as something of an “underground” and “alternative” pursuit from the very beginning.

Much of what we know about yoga today is what we can find through texts. These texts are written accounts of the teachings initially passed down orally. Teachers of yoga wrote sutras, guidebooks, commentaries, and entire philosophical treatises to spread information and ideas about what yoga is and how to practice it. In this way, yogins were artists as well as speakers, tutors, and spiritual guides. Unsurprisingly, many people had various ideas about what yoga was, even in the beginning.

Even though the yoga tradition primarily developed outside mainstream society, yogins still had to interact with the cultural realities of mainstream society to ensure the survival of their knowledge and practices.

Originally, becoming a yogin was a conscious decision to go live in the forests and caves. Eventually, the teachings of yoga were so useful they infiltrated everyday living and were adapted for the householder, revolutionizing the role of the teacher.

From priest to artist: the evolution of the role of teacher

Although Brahmins may not have always been “protected” by Kings, as the Epics suggest, history does provide proof of a healthy patronage system in India that prospered sometime after the 3rd century CE. The ideal of “protection” for the spiritual teacher evolved into patronage, similar to how wealthy and influential European families sponsored painters, musicians, and sculptors like Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, Johann Sebastian Bach, and many other famous artists. In this way, teaching the tools of yoga prospered as a “profession” through a flavor of artistic expression.

Pandit Rajmani Tigunait’s autobiography, Touched by Fire describes the plight of his father who was a pandit, or royal teacher and priest, until India’s traditional government structure changed to a democratic republic in the 1950s, eliminating the royal teacher’s family support structure overnight.

For this reason, Tigunait’s father encouraged his son to become anything but a royal teacher, understanding there was no place for such a profession any longer in India. Undeterred, Pandit Rajmani Tigunait made his way to the US and continued sharing his knowledge in new ways at the Himalayan Institute.

Krishnamacharya also benefited from the patronage system. Sponsored by the Mysore palace to teach and popularize yoga, it was here where much of what we are familiar with today in the West in regards to postural yoga came into existence. This history is documented in Mark Singleton’s Yoga Body as well as in A.G. Mohan’s Krishnamacharya: His Life and Teachings. Krishnamacharya was not a priest or pandit, but much of his accomplishment in adapting and teaching yoga could be considered art.

From artist to fitness instructor: East meets West

Inspired by the work of Krishnamacharya and his famous students Pattabhi Jois, Iyengar, and others, yoga as a discipline began to quickly transform. Propelled by an increasing cultural interest in exercise and the body, yoga became less of a spiritual practice and more of a fitness format in the West. Career descriptions in the burgeoning “yoga industry” transitioned from spiritual teacher to fitness coach. Today, full-time careers in yoga that do not include owning and managing a yoga studio depend largely on leading body-oriented classes.

This transition, while arguably unfortunate, was also necessary to once again ensure the survival of ancient teachings in modern times.

Curiously, the word “instructor” seems to be more fitting for those who lead yoga classes as guided, choreographed group experiences with less time dedicated to teaching the process of yoga.

Finding this balance between what is and what once was always depends on the teacher and his or her views on what yoga is. As yoga continues to evolve, the number of definitions and perspectives on what yoga is increasing.

From fitness instructor to entrepreneur: Yoga meets capitalism

In 2015, CNNMoney/PayScale ranked Pilates/Yoga Instructor as number 10 in its annual list of the 100 Best Jobs in America. The criteria being weighed? Big growth, great pay, and satisfying work.

This report listed annual average income for a full-time yoga teacher as $62,400, top pay potential at $119,000, and highlighted the low-stress quality of life full-time yoga teachers enjoy.

This data does not differentiate between a studio-owning, full-time yoga teacher and an independent yoga teacher. It does clarify that its data is based on answers from full-time teachers with college degrees that have at least seven years of experience teaching (although it doesn’t say whether or not that experience is all full time). Regardless, this was big PR for the yoga industry and painted a pretty rosy picture for anyone aspiring to leave their 9-5 to do work they love (and make a living).

At this time, there wasn’t much information out there outlining what it really looked like to teach yoga full-time. This is why articles such as the CNNMoney report could be so misleading.

Luckily, freelance writer and Pittsburgh, PA, based yoga teacher, Marthe Weyandt, painted a more realistic picture of teaching yoga full-time two years before the CNNMoney report came out.

In her article, Marthe pointed out that even though the yoga industry is a multi-billion dollar business, teachers don’t get the bulk of that money. She warned teachers to plan ahead financially, stick to a budget, and commit to living with less in order to survive on teacher’s pay.

She also highlighted the unfortunately prevalent yet impractical idea in the yoga world that teachers think they can “live on light and happy vibes,” the increasing competition in the industry and associated “meanness” that happens between teachers vying for new opportunities, and the toll teaching takes on the body.

She wisely encouraged teachers to be okay with teaching yoga part-time as a hobby, echoing sentiments expressed as early as 1000 BC in the Dharmasutras.

One year later in 2014, another article was published shining a light on the realities of teaching yoga, this time by Cailen Ascher, a self-described “marketing maven and yoga entrepreneur.” Instead of cautioning against teaching yoga full-time, Cailen struck an optimistic tone while at the same time revealing the necessary business skills that must be developed to make full-time yoga teaching a successful venture. Cailen described the business models of two teachers who did not own studios, teach 20+ classes a week, or travel every weekend. These models included multiple streams of income and online components, something that requires business and tech savvy that are often not taught in yoga teacher trainings. Another pertinent insight:

“They took their time to discover what lights them up, what they truly enjoy teaching, and both weren’t afraid to capitalize on the distinct gifts they possess when building their brand.”

In other words, it took both teachers years to build a successful-enough business to be featured in an online article about what it takes to have a successful yoga business.

Today, Cailen brands herself as a lifestyle design expert, with no mention of yoga on her website homepage. I followed up with her to give her an opportunity to respond to her earlier article to see if her ideas about being successful in yoga have changed. Here’s what she had to say:

“Had I not been patient through all the tough times and lean years, I wouldn’t have been able to reach this feel-good place of expansion and abundance. And it was TOTALLY worth the wait. If you talk to ANY successful entrepreneur or yoga teacher, I’m sure you’ll hear a similar tale. We rarely land on ‘our thing’ right out of the gate, and taking the time to figure it out is an integral part of our development.

To truly succeed in life and business, you need to bring your FULL SELF into whatever it is that you’re offering. For years I tried to compartmentalize — showing up as a version of myself in my business — and consequently, nothing landed fully or delivered the success I desired. When I was finally bold enough to take a stance and show up on my terms, that’s when everything shifted. I stopped trying to become someone and decided to just BE.”

Cailen also mentioned that she stepped away from teaching yoga altogether last year after the birth of her second child, but continues to maintain a solid practice 5x a week.

One of the teachers featured in her 2014 article is the co-founder and director of a successful public speaking training company. Nothing about yoga is mentioned on the website or in her bio. The other teacher is still humming along, even more successful four years later (yay!).

From fitness instructor to celebrity: yoga meets sponsorship (once again)

In early 2017, two years after the 2015 CNNMoney report claimed that the average annual pay of a full-time yoga teacher is $60,000+, Well + Good published an article titled: ”Yes, it’s possible to make $400,000 a year as a yoga teacher, here’s how”.

In all honesty, this article infuriated me. The clickbait headline painted a misleading picture, and the “how-to” tips promoted a celebrity business model—one that, just like in professional sports, most people have a 1-in-a billion chance of ever achieving. One that, particularly in yoga, reinforces a thin, white, bendy body image as the prerequisite for being “good” at yoga and “successful” in business. Even though I have that thin, white, bendy body – I still don’t want to be famous. I just want to share my knowledge of yoga with those who need and want it and contribute to a 401K, to my family, and to a vacation fund because I work hard and I deserve a break every once in a while like every human being.

Admittedly, my pitta-rage gets the best of me sometimes, and in defense of the article, the author fessed up that teaching yoga classes is the least profitable thing you can do to make money teaching yoga.

The article identified event appearances, book deals, brand endorsements, and merchandising as top money-makers, all of which have more to do with selling things than teaching yoga. At least teacher training facilitation and creating content for online educational platforms made the list as well.

In an unrelated but refreshingly honest comment on a blog post written by J. Brown, long-time yoga teacher Andrew Tanner had this nugget of wisdom to share about teaching yoga full time:

“…Our culture since the 90’s has been telling every child they can be ‘anything they want to be.’ Hence the entitled idea that just anyone can make a living teaching yoga. Stats from Yoga Alliance tell us that less than 7% of yoga teachers teach full time and less than 25% of YTT grads ever teach professionally…The problem is that many people don’t like the trade-offs that the reality of modern life presents. It’s a sacrifice for a yogi to learn to use social media effectively. Or obtain business skills, or studio marketing, or partner with someone who does…[A] lot of teachers decide not to try to make a living teaching yoga and they should be at peace with that. They shouldn’t be lamenting a world that never existed, i.e. one in which every great yoga teacher made six figures teaching yoga without any entrepreneurial hustle. That’s just a big lie. Even Krishnamacharya and Iyengar marketed themselves like crazy doing events and public demonstrations to make a living. I’m sure they hated that…but that’s what it took and that’s what it takes.”

So, should I try to be a full-time yoga teacher?

At the beginning of 2017, I wasn’t finding the information or support I felt I needed to be a successful yoga teacher making $60,000/year like CNNMoney infamously promised. Some articles said don’t do it, while others said do it, and you’ll make a ton of money, which I knew from personal experience wasn’t exactly true.

There’s a haunting question born of self-doubt that creeps on the border of most every yoga teacher’s subconscious mind: “Should I go back and get a real job?” In moments of despair, this question crosses over into conscious thinking with a roar, reminding us that we are inadequate and crazy for even thinking we could make a good living and love what we do all at the same time. We check job listings in the career fields of our “past lives.” We reconnect with a few old colleagues to “see what they’re up to” even though we’re really feeling them out to see if they might be able to help us in an upcoming job search. We crumble into a heap and cry on the bathroom floor, our tears seemingly washing away our hopes and dreams.

There’s a haunting question born of self-doubt that creeps on the border of most every yoga teacher’s subconscious mind: “Should I go back and get a real job?”

Then we get up and go teach a class and forget it all. Newly inspired and motivated by the energy of a class of yogis laying at peace in Savasana, we go back to the drawing board and begin the cycle anew. Until next month. The wheel keeps turning.

The full-time yoga teacher project

A question I often ponder is whether teaching yoga is a smart career choice. This question is based on economic concerns, such as the viability of supporting one’s self and family on the average salary of a yoga teacher (what really is the average salary of a full-time yoga teacher?) and the sustainability of a career path that includes inevitable wear-and-tear on the body and nervous system.

Was India on to something when they “eliminated” the profession of “royal teacher” and cast the knowledge out into the marketplace for individuals to do with as they pleased? And how has the Information Age contributed to or degraded the spiritual knowledge that yoga teachers hold the responsibility to learn, practice, and share? What is the responsibility of a yoga teacher?

I have high hopes for the future of the yoga profession. It is the inherent nature of yoga to change, and I know that yoga teachers can come together so that we can all figure out how best to ride the waves of change into the future.

Bonus: thoughts on the state of teaching yoga full-time in 2018

After interviewing over 50 full-time yoga teachers across the world to figure out how they make full-time yoga teaching work for them, I’ve pulled out some of the highlights and advice from the stories I heard.

“At the end of the day, this is a very competitive industry because of the market saturation. There are yoga teachers everywhere vying for the same opportunities. Decisions get made behind closed doors. We’re not paid fairly. All of this leads to feelings of mistrust between teachers, which is misplaced because the entities we should be directing our mistrust toward are the people actually making the decisions. To feel supported by a community is a two-way street. You have to feel like you belong in that community, but you also have to feel confident in your place in that community.”

“I’m just interested in building community. I think for those of us trying to make teaching yoga as a full-time job work it takes a lot of fortitude and creativity. I’m interested in figuring out this puzzle.”

“Teaching yoga is competitive, and there are so many great teachers out there. It can feel like you’re very much in it alone, especially with social media — we’re constantly seeing our fellow teachers promoting awesome retreats and trainings. Sometimes it feels like everyone else has got it together. Talking to people and sharing my fears with other teachers has always been one of the best tools for feeling supported. I don’t know why people don’t talk more about what they struggle with in yoga teaching.”

“I wake up in the morning and think I need to do my Instagram post. People think you just teach yoga — that makes up maybe five hours of my week and the rest of it is trying to get butts in seats. There is a lot that happens behind the scenes.”

“I don’t believe teaching yoga is a career. It’s a hobby job at best unless you are fulfilling a niche. You cannot survive on teaching classes at your local studio. You can’t be teaching 25 classes a week. The yoga celebrities are actors. How many actors are there and how many of them make it? If you love yoga, it’s a nice part-time job. I teach online courses in empowerment, I work with eating disorders, I have a lot of other jobs that I do. If you’re thinking about quitting your job and teaching classes for a living, you’re going to have to do something else. The average yoga teacher makes $25-50/class where I live. So how many classes do you need to teach to pay your mortgage, car payment, put your kids through college, etc.? Teaching public classes is a hobby job.”

To learn more about Ashley and download her free report on the state of teaching yoga full-time, visit her website.

Illustration by Katya Uspenskaya

Edited by Leanne de Araujo

Enjoyed reading this article? Consider supporting us on Patreon or making a one-time donation. As little as $2 will allow us to publish many more amazing articles about yoga and mindfulness.