We live in a world made for extroverts. How loud you talk defines how smart you are and how successful you ought to be. We think highly of the light of the party, the one who cracks jokes, the one with the funny anecdotes — much more highly than of the one who disappears mid-house-warming party, to be found playing with the cat or pretending to be fascinated by the magazines lying on the coffee table.

The cheerleading squad always enjoys a better reputation than the chess club; we are told to aspire to become a well-connected trader rather than a lone artist. And, for some objectively illogical reason, we tend to find it sadder to spot someone having lunch lost in a book instead of surrounded by a loud group of friends.

The world would be a gentler place — at least to introverts — if the soft-spoken and the loud were equally respected and valued for their inclinations and strengths. And isn’t that what yoga is about? Bringing a little more softness into the world and, as cheesy as it may sound, a little more love?

Consider this article a journey into the mind of an introvert; some of us may be quiet, but our inner worlds couldn’t be more colorful and vibrant. First, I’ll share a bit of my own experiences and how my introversion has impacted my day-to-day. Then, with the help of Susan Cain’s research into introversion, we’ll uncover some of its meaning and implications. At the end of the article, you’ll find pointers as to how and where to find introverts along with a list of resources to dig deeper.

Whether or not you’re an introvert, and whether you can point to loved ones who are, I invite you to read the following words with an open mind and heart as I debunk some of the most common misconceptions we have on the true definition of introversion.

“Our culture made a virtue of living only as extroverts. We discovered the inner journey, the quest for a center. So we lost our center and have to find it again.” — Anaïs Nin

Myth #1 Debunked: Time Alone Isn’t the Point

Are introverts loners?

Myth: Introverts love to be alone.

Reality: Introverts need to recharge after social interaction.

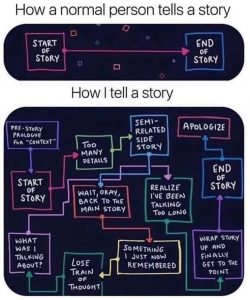

Growing up (and older), I always thought I was a bit of a weird person. I like(d) what could be considered ‘nerdy’ by the average Joe, like extraordinarily well-written books and big questions no one knows the answers to (one of my favorite Ted talks). I get (really) excited when I learn something new, when I make a new connection between old and new things, when I get new ideas, and my eyes light up when I’m in the middle of a deep conversation about the latest social issue or learning about the differences between life in Japan and Chile. I highly dislike small talk even if I understand its necessity. I’ve always felt awkward in group conversations —and yet I love people— and I never know what to say, answer, tell, when put on the spot.

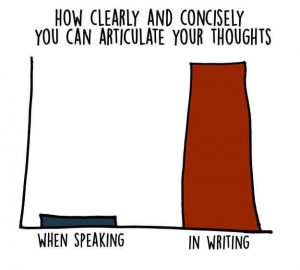

It’s as if my mind turned blank, or that suddenly all the cables that were supposed to take an idea from point A to B got crossed, like 2 pairs of headphones of the same color in a jeans pocket. It takes a tremendous amount of energy to untangle them —and in group settings, by the time I’ve managed to make sense of my thoughts, we’ve already moved on. The topic has changed, I’ve missed a joke, and I have to start all over again. Needless to say, I never really feel like a fish in water in those settings.

Those inclinations have made me spend significant amounts of time alone, bent over books or lying on my bed staring at the ceiling, headphones plugged in, listening to my favorite songs on repeat and lost in thought. I have preferred to spend time with one friend at a time, with the rare exception of birthday parties and gatherings my parents organized on Sunday afternoons to share crêpes. After such events, I was quick to climb back up in my room and into my comfy mezzanine lair of a bed.

I was an introvert, that’s what they said, but I never really liked that label. It seemed to clash with how curious I was about people from all over the world and how much I enjoyed human company. I had yet to discover what science says about the lively minds of introverts, and back then I just knew one thing: I needed my self-assigned time alone. It wasn’t so much about having time alone as it was about choosing where to focus my attention —and I was fine with keeping how much I loved it a secret.

It wasn’t that I didn’t want to be around others; I did enjoy nights out dancing or afternoons spent at coffee shops with friends. It just took a lot out of me, and it often felt like I was investing a lot of energy into a single activity.

My time alone allowed me to breathe a little deeper, to have conversations with myself without calculating. My moments allowed me to stop thinking twice about what to say —to keep the audience focused—how to say things —so it would be entertaining— or what to do —to show I was full of life. These moments enabled me to reconnect with myself, to give my nervous system on overdrive a break, to check in with my quieted needs and give them the attention and space they called for.

Myth #2 Debunked: Introverts Love Human Connection, Too

Are introverts anti-social?

Myth: Introverts hate people.

Reality: Introverts love (and need) human connection, too.

I was also lucky to spend the last two years of high school among fellow “nerds.” They appreciated Baudelaire’s poems, and they laughed at our old history teacher’s jokes on the art of table setting and tableware in 18th-century aristocratic France (I kid you not). We’d exchanged notes in class to discuss our latest heartbreaks, and it wasn’t impossible to get your philosopher friend’s latest thoughts on our perception of time and space instead of the usual teenage angst. There was always a way to link those deep ideas to their impact on a teenage love affair; getting the usual angry swearing wasn’t a habit of ours. Instead of “leave the idiot” type of suggestions, we’d much rather get into lengthy discussions about the meaning of love.

“Time doesn’t exist. It’s a succession of actions and states of mind one after the other. Three years might go by, and nothing will have changed. You’re the one to move. Time only moves because within it, you act.” — one of those sentences written on a piece of paper by my philosopher friend in grade 11. Somehow I always find ways to apply it to life, and today it makes me want to act to bridge this gap of misunderstanding between introverts and extroverts.

We were outcasts, then — that’s what we would be called for always preferring quiet settings for our deep daily conversations, teased for taking jokes too literally, or never showing interest in morning chitchat. Only some of us could be “lucky” and fall into the right family, or the right country, to never hear that we were too quiet.

If I didn’t have a family and friends who respected my needs to opt for quiet nights in instead of big parties, my life wouldn’t be as easy. And in many places around the world, it’s very normal, in fact, to be an unlucky introvert, the one stuck with the “antisocial” label on. In some places, it’s particularly valued to always have something to say, even if it’s not really interesting —think the US. In others, you need to be able to enjoy loud noise on the street or in your house during family gatherings —think Mexico. Elsewhere, you’re expected to spend extra hours on work rather than let a nervous system on overdrive rest —think Singapore.

For introverts, those are all situations where we feel we don’t exactly fit, and yet it’s not really about the people. The best-case scenario is to find yourself in understanding company or with family; the worst is to have your loved ones and colleagues ask you, in what feels like an attack, to “get yourself together,” “stop hiding, already,” and “make a little effort.”

And if you’re of the “shy” or “too sensitive” ones pretending to be part of the “cool kids” as a teenager, every day is an identity crisis. In adulthood, it’s just as hard, especially if we can never find the tools to accept ourselves as we simply are. Having to hide can feel extremely isolating and completely break your self-esteem and confidence. How can anyone go about life wearing such a heavy mask? It’s tiring at best, massively destructive at worst.

To fit in as an adult, I had to force myself to show up at parties and be part of the group. I was expected to say something during work meetings and to know what to say even when spontaneously put on the spot. I was expected to attend every single one of the big events my friends organized, even if I knew they were just going to be long stretches of discomfort for me — was it the music, the people, the expectations, or all of it? I wasn’t exactly sure.

Either way, I felt like an outcast, and often still do. But my dislike of huge crowds and noisy parties doesn’t mean I don’t need human connection —we’re social beings, and we all do! As introverts, we just need different connection than extroverts do. We tend to prefer a quiet one-on-one conversation with a friend to a night out at the bar, and we are like to enjoy making online connections more, where we’re allowed to stay in the comfort of our homes while exchanging ideas. And if we do enjoy the occasional dance party, we can most likely be found recharging the day after (maybe even the week…).

Professor Slughorn’s hourglass in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. The sand runs quickly if the conversation isn’t deep, and slowly if it is. When the hourglass is mentioned, Harry and Slughorn have a deep conversation about Voldemort, and the sand almost freezes. Deep conversations feel like that: like time is freezing, like the only thing that matters are the ideas presented, argued, and discussed. The challenge becomes to find the curious minds who’ll have those debates as often as time allows.

Myth #3 debunked: No, We’re Not “Overreacting”

Aren’t you making a fuss out of nothing?

Myth: We overreact.

Reality: We’re really sensitive.

I have a burning love for deep conversations, silence, and the art of well-combined words or music notes, and get deeply unsettled by any sort of violence. They’re normal passions and aversions, you’ll say, but the way they’ve influenced my day-to-day has sometimes felt problematic. My sensitivity, especially when I find myself surrounded by vocal strong-headed decision-makers, always seems to be in the way.

Whenever, within a group setting, it’s time to opt for a movie or any kind of TV show, and the needle falls on the kind of content where doctors operate (Grey’s Anatomy, Pearl Harbor) or fight scenes are likely to pop up (any Marvel movie, Game of Thrones), I know I’ll have a hard time. Although I know better now and completely avoid those kinds of content, there was a time when I didn’t have the courage, strength, or confidence to voice my preferences.

My heart would beat hard in my chest, and air would suddenly go missing. I’d jump up at any unforeseen activity and would have to imagine the green screen used on sets to add special effects after filming —trying to remember it wasn’t real.

During my second year at university, I was half-convinced to go watch The Conjuring on a Saturday night; my friends argued it wasn’t that bad. I spent the whole movie hiding my eyes and whispering “ohmygodohmygodohmygod,” taking deep breaths in, half-smiling and realizing how ridiculous I was being, trying to remember that it was just a movie, and hearing my friends laugh heartily at my (over)reactions.

Needless to say, we came out of the cinema bursting out laughing; I promised myself to never ever even let others try to convince me a horror movie wasn’t that bad.

The only way you could make me watch that kind of violent content would have to include you already knowing exactly where I have to block my ears (visuals without sound are, so it happens, much easier to watch). You’d also need a really deep reason why I’d have the slightest interest in dedicating two hours of my time to such content. It should hold deep lessons and pointers towards a specific issue (like in a few Black Mirror episodes), or be a brilliant depiction of the dangers of patriarchy or religion in our world (The Handmaid’s Tale), for example. Later, I learned that there is a scientific explanation for that: it has to do with the disposition of the brain, which I tell you about later on. Keep reading.

That heightened sensitivity doesn’t discriminate: responsive to the Ugly, yes, but also to the Beautiful. Boring and uneventful movies, TV shows, and books are what I call my favorite genres. To me, they’re beyond stimulating —and all my nervous system can handle. They’re the kinds that give me time to think, process, absorb. They make my heart soar, help me find hope and love, make me feel connected to my fellow humans, and feed my optimism. They’re animated movies (Coco), love stories (About Time), creative TV series (Jane the Virgin). They’re the kind I can watch a few times and still notice details I’ve missed, extract lessons about (our) humanity, and feed my creativity with.

Here again, we get called names for our tendency to jump in our cinema chairs, say no to roller coasters, or simply prefer to take the bus rather than fly to our travel destination. Those choices make our lives significantly easier, but do come with the price of recurrent eyerolls.

This time, delicate might be the word that fits my sensitive peers and me. This one feels much more isolating than nerd; it imprints on our brains that, come on, we should be able to stay put in these situations. They tell us when it’s deemed normal to “over”-react, and when it’s not. They give us the impression that being in a state of distress “so easily” is “over the top,” that we’re “overdoing it,” as if our reactions were those of kids who get upset because they didn’t get the ice-cream they wanted so badly. Yet if it were a matter of choice, we’d make it; life seems so much easier when your environment doesn’t impact your heart rate and nervous system so much.

Myth #4 Debunked: Shyness Has Nothing to Do with It

Aren’t introverts just shy?

Myth: Introverts are inherently shy.

Reality: The way we process information makes it difficult to say the expected thing in social interactions.

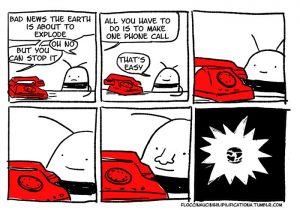

Growing older becomes a double-edged sword. With age usually comes more acceptance of who you are, and the realization that everyone deals with the same questions and feelings is very comforting. On the other hand, responsibilities become unavoidable and, unless you find a roommate or a partner who gets it, calling the plumber or booking an appointment with the hairdresser cannot be indefinitely postponed. And believe us, we try.

Unless calls are absolutely necessary or I have a strong feeling they would make me feel comfortable enough to allow as few moments of awkwardness as possible, I dismiss them. I’ve had to call my health insurance for about 2 months now, and I still haven’t found the courage to add it to my to-do list. The person on the other end of the line expects me to talk fast, to be reactive, and I know I’d stumble on my words —no matter what language I use.

Job interviews are nightmares; you have a mere few minutes to show your potential future boss you know how to organize ideas —something that came easily to you when choosing the words in your cover letter— and pretend you’re breathing normally effortlessly.

I always feel like I think about 10,000 things at the same time. When the proper outlet helps me organize those thoughts —a mindmap, a word document, an excel sheet, a blank canvas— I can slowly make sense of it all. But right there, sitting in front of the stranger who might become my boss, or wondering whether what this person in a bar just said was a pick-up line, I freeze. I simply don’t know how to respond. Not because I’m too shy to say what’s on my mind; it’s because I have too many options to choose from.

Over time, and thanks to Susan Cain’s Quiet Revolution movement, I’m learning to navigate those sensitivities and invite my fellow humans to pay attention to them. I’ve learned that I can find easily overwhelmed souls like myself online, and we connect in the DM section of Instagram or in small Facebook groups. I’ve learned that if I stay up late and dare to come write in the living room of the hostel I’m staying at, I’ll find the quiet ones bent over the history of the town I’m staying at or deep in conversation about the one piece of art they discovered that day. And I’ve learned that if I want to enjoy a hike with others, I invite those people to join me, and we can stay minutes or even hours watching a sunset without talking. Or ask the quirky questions, like how would it be if we still believed the Earth was the center of the Universe and the Sun gravitated around it…

I opt for online yoga; not only is it what my wallet can afford, but it’s also much easier to keep practicing when you can choose to not play music and the amount of light you need. And in the comfort of your own space, you can allow your mind and heartbeat a little more quiet time in savasana, free of judgement.

“[Introversion] is different from being shy. Shyness is about fear of social judgment. Introversion is more about how do you respond to stimulation, including social stimulation. So extroverts really crave large amounts of stimulation, whereas introverts feel at their most alive and their most switched-on and their most capable when they’re in quieter, more low-key environments. Not all the time, you know, these things aren’t absolute, but a lot of the time.” — Susan Cain in her Ted Talk, The power of introverts

Anyone who has read this so far and feels identified knows the moments of discomfort and misunderstandings never really come to an end; no matter how much we learn to pretend (or not), those sticky and icky situations continue to happen, and they will, as long as our world continues to put the extrovert ideal on a pedestal.

As long as it’s not okay to be the one sitting at a table with a book or all the arts and crafts without being considered a weird bug, then I’ll make it my mission to share with the world that introverts aren’t nobodies, and that science can explain how it all works.

Quiet Epiphany — We’re Just Normal, After All

One fine summer afternoon the year I graduated from my master’s, I stumbled upon a Buzzfeed article featuring a list of doodles that represented what it feels like to be an introvert. Excited and curious, I clicked, and found this one:

An epiphany reading “Quiet” by Susan Cain? My heart leaped into my chest, and I made a note to get myself the book. The next day, I download Audible, and Cain’s book is available for the free trial. I begin listening to the audiobook. I find out the subtitle is ‘The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking.’ This, on its own, led me to utter a heavy sigh of relief — there’s just so much noise everywhere, and the author gets it!!!

I listened to the book everywhere and whenever I got the chance to. On my bike to work, on my bike home from work, on my way to dinner, while cooking, and mostly carving out time to simply lie down and listen, wide-eyed and more eager than I’d ever been reading (listening to) a book (okay, a close one with the Harry Potter books).

Suddenly, someone was telling me it was okay to strongly dislike small talk, to choose to not watch horror movies because they’re just way too much, to want to spend Saturday afternoons learning, to enjoy (very) long bus rides daydreaming. It was okay —and normal!— to want to spend hours thinking and writing about life, the world, love, the evolution of cats, and other topics deemed fit for philosophical reflection (which is, well, everything, if you ask me). I understood why, some days, I physically need to come home to silence, even if those days are just filled with barely any more conversations, noise, and information.

Myth #5 Debunked: Introverts Don’t Have an Aversion to People, Just a More Sensitive Amygdala

Don’t introverts hate people?

Myth: Introverts are anti-social.

Reality: A sensitive amygdala makes us easily overwhelmed, automatically pushing us to avoid overstimulating situations like group settings.

Susan Cain uses countless studies to explain why some people jump in suspense or thriller movies, why they also tend to be disturbed by loud noises and bright lights, and why they’re less likely to respond to rewards. One of her findings was that introverts tend to have a more sensitive amygdala, the organ in the brain that tells us how to respond to our environment, and where fear originates from.

“The amygdala serves as the brain’s emotional switchboard, receiving information from the senses and then signaling the rest of the brain and nervous system how to respond.” — Chapter 4: Is Temperament Destiny? Nature, Nurture, and the Orchid Hypothesis.

Introverts are sensitive to their environments, which can explain why they tend to be increasingly drained out of energy during a social gathering. It’s not because of people; rather, it’s about the sum of factors found during such gatherings: music, lights, smells, conversations, food, drinks —everything (like on the drawing in the Myth #3 section).

This discovery explains why introverts need to recharge after any kind of social interaction or event.

The study of introversion tells us introverts are the kids who spend more time inside playing with their toys than with the neighbor; they’re the new mom who needs particularly strong boundaries with the rest of the world; they’re the high school teacher who doesn’t play music on their 30-minute commute home.

Rather than a condition, of course, being introverted is more of a spectrum, not a cookie-cutter kind of trait; each of us will feel responsive to stimulation to different degrees. So although examples like those of the kid, the mom, and the high school teacher show common ground in one way they experience the world, there are still many instances where they’re not likely to react the same way.

And the same way introverts can be more or less affected by their environments; extroverts can be interestingly highly unaltered by them. Alex Honnold, the first man to free climb the 900-meter (3,000-foot) vertical rock at Yosemite National Park in June 2017, is on the exact opposite of the introvert-extrovert spectrum. In the documentary that retells his outstanding adventure, researchers test his brain’s reaction to fear, and they find that his amygdala is particularly less active watching terrifying and provocative photos. One of the reasons he’s so resistant to the terror that might creep into any of our minds while contemplating such challenges is because he feels it to a much lesser degree.

Thus, neuroscience shows that while an introvert would have her heart jumping out of her chest merely considering such feat, Alex could climb to the top without ropes in a mere few hours. We haven’t mentioned anyone’s aversion for —or lack thereof— people, and yet it could be strongly argued that Alex is a true extrovert, based on the aforementioned research findings.

When it would easily be assumed that introverts hate people when they decline invitations to partake in what they consider highly stimulating events, the decision-making that happens on the inside is a little more complex. An inclination to avoid demanding events such as a day spent group kayaking, a clubbing night, a massive beach lunch picnic might merely depend on the settings.

If you’re curious to experiment the argument with your introvert friends, simply alter the conditions: invite them on a kayaking trip with just the two of you, choose the lesser known dancing places (preferably neon-light-free), a sunset gathering with your closest friends (4, not 10), and see what they decide on.

Myth #6 Debunked: Shy, No; Rather, Slow Starters

Aren’t all introverts shy?

Myth: Introverts are inherently shy.

Reality: Introverts pay attention to details and process them deeply.

Do you recall the example I gave about interviews or party encounters? That they were particularly challenging, and that it had nothing to do with shyness? Although fear might come in the way too, often, the problem is that we freeze when limited by time.

Studies have pointed to the way we process information and found a link between high sensitivity and inclination to process environments “unusually deeply,” and that “sensitive types think in an unusually complex fashion.” (Quiet, Chapter 6) This might explain why sensitives — and/or introverts— find it particularly difficult to understand a joke other than literally, or why touching only the surface of topics such as the weather or the weekend can feel a little boring. What is there to process deeply in tomorrow’s temperature or the adjective “good”?

And so yes, deep processing takes a little more time. Introverts might be a little slower to respond to messages, to have projects see the light, and understand a math problem straight away. It’s not necessarily because they lack the brains to understand, it’s because information likes to travel to different places in their heads, connect to similar problems or stories they heard or lived —and that’s just another way to receive and share information.

Quiet is filled with such examples and historical illustrations showing how introverts and extroverts fill in exam sheets or lead political upheavals, why the former need extra time to make decisions, and the fundamental reasons why it’s normal to be an introvert and still enjoy — and want — human connection. The final part of the book, How to Love, How to Work, even gives practical pointers and tools to navigate relationships and the workspace. Whether you’re an extroverted parent with an introverted child or an introverted boss with many extroverted colleagues, there is a way towards understanding and co-living.

Introversion, then, isn’t a matter of how shy someone is —although the two traits might overlap— or how little time introverts want to spend with fellow humans. It’s about differences in sensitivity to stimuli, dopamine levels, nervous systems, attention paid to our surroundings, decision-making and thinking processes, and more (to learn more, go to the resources section of this article).

Recent psychology and neuroscience research shed light on how and why introverts may be repelled by small talk and adore (yes, adore) meaningful conversations. And that summer I spent reading Quiet, The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, I read one of the most reassuring and liberating books of my life.

It allowed me to let out a big sigh of relief; it made me feel less alone and understood.

It showed me I didn’t really need to pretend or try too hard anymore, that I was just normal, after all. My sensitivity could be seen as a quality rather than a burden. I felt I could reclaim my right to appreciate a beautiful sunset, admire a poet’s work, or want to be a voice of change in our world.

And most reassuring of all, research told me I had the right to take care of my well-being the way I saw fit. If I chose to prioritize moments of silence and restorative yoga, then that’s how I was allowed to have it. I didn’t have to force clubbing and action movies into my list of passions like you force brussels sprouts down a child’s throat —I was free to simply be.

Our Social World’s Shortcomings, and The Need to Redefine Introversion

And if only it were that easy.

Despite Susan Cain’s pioneer work and the number of ways wonderful humans have responded to her initiatives, the road is still very long. Clichés still live on, but as of now, science, historical references, and political examples show how little introversion and extroversion have to do with being shy or anti-social.

At the time of writing, I was a resident of the United States; and if I’d been surprised by the examples Cain mentioned in her book when it came to the extrovert ideal in this country (an entire part is dedicated to it), I was even more disappointed to see that many of those cultural habits are mere examples of everyday life.

In the US, TVs are on all the time (even at restaurants with candles on the table), and small talk is a social activity even introverts know how to do. It’s impossible to avoid traffic —at least around New York— and at the bakery, there is a staff woman in the line making sure it’s moving properly, read: fast. Although I disagree with the supposedly economic necessity of bringing the check to the table while customers are still chewing their last bite, fork in hand, I understand it. But these situations feel unsettling for me because they force me to be reactive and stay on my toes at all times, and it’s really draining.

But change will take time to happen; it’s exactly why it’s important (and certainly fascinating) to discuss the ways introverts’ and extroverts’ minds differ, and how we can protect, respect, add to, and enhance each others’ lives.

If we look at the etymology of the word introvert, we find it was first used to describe a state of contemplation, a moment spent bent over our inner worlds, in the mid-17th century. The meaning of introversion, as we know it today, was first coined by psychologist Carl Jung at the beginning of the 20th century and later popularized by personality researcher Hans Eysenck, linking it to sensitivity to stimulation.

Thus, introverts are not hermits, nor do they want to be, and the lexicon was never intended to describe such non-existent intentions. Introversion is about a propensity to notice our environments and how significant an impact they have on our overall wellbeing. It’s about how they influence our ability to focus, to feel grounded and connected to ourselves, to take action in the world.

So, the key lies in observing and noticing who we share experiences with and the ways they might differ. It’s like turning into a detective, asking two people how they remember the same event to get the full picture. In it, where are introvert hiding? And how might we find them?

Fantastic Introverts — and Where to Find Them

Struggling to identify introverts in your surroundings? Here are a few scenarios that will help you recognize an introvert among your friends, coworkers, and yoga students. If you consider yourself extroverted, I invite you to keep an open mind and heart and to look at these situations with curiosity.

Your introverted friend is the one who will go home after a night out not to go to sleep, but to spend a few more hours awake reading, listening to soothing music, writing, drawing, playing, meditating, or just looking at the ceiling. They’re the friend who might notice the tiny tweaks in your living room shelf organization or the slightest change in your mood.

Your introverted coworker is the one who remembers the thing you said in a meeting 3 months ago, took note of your idea, and made a link with the one you just presented now. This colleague, however, might not be the one making the decision as to where to take this combo, and is even less likely to do so straight away. She might also wait until she’s out of the meeting room to write more of her ideas in a long email to the team.

Your introverted yoga student is the one who asks to lower the music down or dim the light. They’re the one to send you a message to ask a question even if they were in your busy group class just a few minutes ago. They’re the ones who attend both your vinyasa and candlelit meditation classes, and who wish they could attend your 10:30 am classes where they know fewer people are likely to show up.

Your introverted yoga teacher is the one who prefers to teach few classes, who shows up just a few minutes before class —not necessarily because she doesn’t want to strike a conversation, but because she feels it crucial to keep her batteries up for when the class begins. At times, she’ll come early to meditate, pretending to be lost in breath with her eyes closed as students flow in. She might be an extraordinary meditation teacher, too —something about her energy manages to soothe and calm you in the most heart-warming ways.

Your introverted customer asks for decaf coffee and herbal tea even at the early hours of the morning. They’re hidden under blankets on the night buses, even if they could potentially have flown in. They’d rather bike than take public transportation, not because it’s good for their bodies, the environment, or their bank account, but because they desperately need to stay away from the noises and lights and buzz of crowds during afternoon rush hour.

Your introverted friends choose to find the peace and quiet they need to recharge as often as they can. They might go above and beyond to make sure they have a chance to close their eyes and rest, reflect, pause —and that’s as much of an act of survival for them as it is for you extrovert take in all the outside world input you can get.

Towards More Understanding for More Freedom

When we commit to dedicating time to understand each other —extroverts and introverts alike— practicing and cultivating compassion, we make the space we share more tolerant and open-minded and thus more enjoyable for everyone. We allow each of us to experience the world the way we feel most at ease, supported, and free.

Knowing how differently we work, we can also help each other out where one falls short. Many curious introverts would love to learn how to experience social gatherings without breaking into a sweat or wanting to leave as soon as they arrived. Extroverts might use help to learn how to enjoy (and reap the benefits of) alone time. And wouldn’t it be lovely to rely on and trust each other a little more?

“Now, this [matching extroverts’ choices] is what many introverts do, and it’s our loss for sure, but it’s also our colleagues’ loss, our communities’ loss. And at the risk of sounding too grandiose, it is the world’s loss. Because when it comes to leadership and creativity, we need introverts doing what they do best.” — Susan Cain in her Ted Talk

Susan Cain’s book, besides being exceptionally well-written, changed my life —and that of many fellow introverts. She has helped millions of us stand our grounds and set the boundaries we desperately need to be able to go through life with the energy and confidence everyone strives for.

Now, human personality is complex, and no one word can contain all the ways our traits interact with each other and show in our lives. Although it’s very tempting to simply put everyone in black and white boxes, it wouldn’t do our lively personalities justice. Besides, our identities and temperaments are bound to evolve as we learn, grow, age, which is why the matter can’t simply be done and dusted. Trying to put introvert and extrovert stickers on everyone’s foreheads would be limiting, at best, dangerous at worst. When we close the door onto complex topics and situations, we close the door on open conversations, and therefore, on understanding, empathy, curiosity, and tolerance —a recipe for social disaster, if you ask me.

Being able to recognize tendencies, however, can be incredibly useful so we can be better friends, lovers, teachers, parents, workers, and more. What we all have to remember is that the actual differences we show are never as big as how we perceive them. Introverts might climb walls like Alex Honnold or become public speakers. Extroverts can enjoy a stunning sunset or deep conversations. If that weren’t the case, humanity would be in serious trouble, and it would be incredibly difficult to bridge the gap between our psychologies. Extroverts can also tell a story with many detours and be detail-oriented. Introverts don’t own the right to enjoy silence or poetry, either.

May we simply remember that it’s okay to experience the world differently, and may these differences be our secret weapons to richer, more fulfilling lives and shared experiences. After all, as Susan Cain writes, Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King complemented each other in the fight for civil rights; they did it their own way, and none was more valuable than the other.

In the end, all humans want freedom. We want to feel free to be who we are, with our quirks, flaws, and strengths. We want to express ourselves, make decisions, take life directions that bring us closer to that sense of freedom. We want our life stories to be ours, to be true to what we believe in and value. When we embrace introverts and extroverts for who they are, with their own unique ways to go about life, we get to experience the liberation we all long for.

Dig Deeper

Below, you’ll find a few resources to continue this journey of self- and alter-exploration.

Reads

Quiet, The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain

Exceptionally well-written, mixing history, politics, personal examples, and science, Susan Cain’s book This is obviously where I’d recommend you to begin.

Quiet Girl in a Noisy World by Debbie Tung

Compilation of comics illustrating the everyday challenges introverts might go through.

4 Lessons I’ve Learned as an Introverted Black Girl by Nichole Nichols on QuietRev.com

“Since our personality type is opposite of the loud, irreverent black woman stereotype, many people are perplexed by us.”

I’m an Introverted Woman in Tech, and I Want to See Introverted Women Succeed by TD.

Appeared in the “Code Like A Girl” publication, one that celebrates breaking down society’s perceptions of how women are viewed in technology (on Medium.com).

Why Is Being an Introvert Difficult in the Workplace? By Ashley Burk on Introvert, Dear — 5 “pitfalls” of the extroverted workplace.

The Science of Success by David Dobbs

Dobbs explains the Orchid & Dandelion Hypothesis by Bakermans-Kranenburg, a study mentioned by Susan Cain (Chapter 4) on how one’s ability to grow can depend on the environment and one’s sensitivity to it.

Art & Comics

Introvert Doodles by Marzi. Imagination meets anxiety and introversion; there you have Marzi, who Shut Up & Yoga interviewed! Read the interview.

Gemma Correll’s doodles Quirky, fun, cute.

Liz and Mollie’s drawings L & M illustrate the everyday professional challenges and, among others, advocate for embracing feelings at work.

How to live with introverts, a short comic by Roman Jones

Illustrations explaining how the introvert brain works based on Marti Olsen Laney’s book The Introvert Advantage

A short comic by Luchie illustrating the frustrations that can come with not feeling understood if you decide not to go out (or to go home quickly).

Comics That Perfectly Illustrate What It’s Like Being an Introvert

The Buzzfeed article I stumbled upon that summer, These comics perfectly illustrate what it’s like being an introvert

88 Comics that Introvert Will Understand

Definitely bookmark this one for the days you feel a little lonely.

6 illustrations That Show What It’s Like In An Introvert’s Head

A few of those drawings appeared in this article, too.

Watch

Susan Cain’s passionate Ted Talk

How to meet like-minded people by The School of Life

If you crave deep, thoughtful connections, then this video is for you.

How to approach strangers by The School of Life

Illustration by Katya Uspenskaya

Edited by Sarah Dittmore and Jaimee Hoeffert