How would you describe your mobility? Perhaps as the depth of your forward bend in Paschimottanasana, or whether or not you can do frog pose. The word mobility has been used in a lot of different ways, often loosely without a clear definition to distinguish it from flexibility. For example, on the Functional Anatomy Seminars website homepage, they define mobility as: “Mobility refers to the amount of active, usable motion that one possesses.” In his Shut Up & Yoga article “Your Brain on Yoga pt. III,” Dr. Garret Neill defines mobility as “the ability of a joint to move actively through a range of motion” and “range of motion you have active control over.” In contrast, flexibility, in his mind, is “range of motion you may, or may not, have control over.”

In his book Better Movement, pain science expert Todd Hardgrove defines mobility as “the degree of functional control over the end range of motion,” and flexibility as “the range of motion at a particular joint—how far it can move from A to B.”

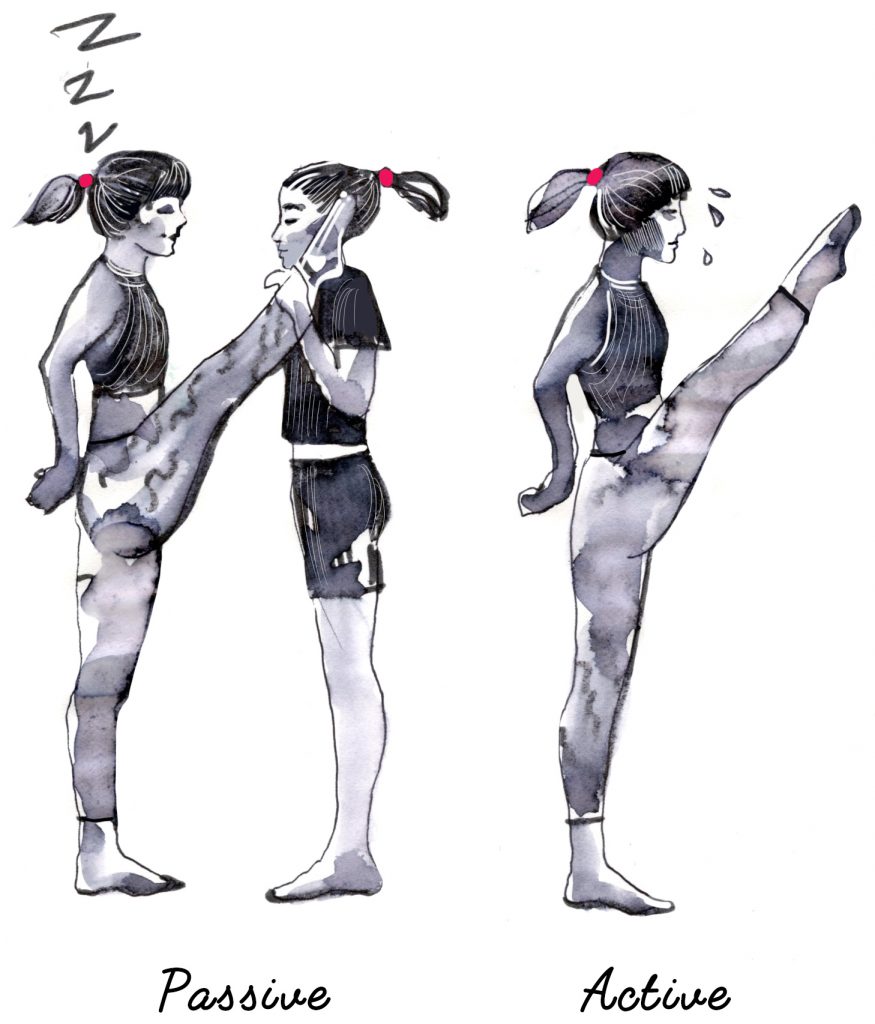

What all these definitions share in distinguishing flexibility from mobility is leverage. If we want to explore flexibility, one of the easiest ways to do so would be through stretches and movement that leverage joints into their passive end ranges of motion (pROM). Since we do not always use muscle force to actively control our joints at their end ranges, we refer to these joint ranges of motion as “passive.” It’s good to note that we always have more passive range of motion available to our joints than active range of motion. Going back to our discussion around the difference between mobility and flexibility, we can work on flexibility with the help of external leverage from other parts of our body that are extrinsic to the joint: with props to tug, pull, leverage, or fold the joint; and with plain old body mass, since gravity acts on the joint to produce body weight. For instance, we can pull our knees to our chest with our hands in Apanasana to explore passive range of motion in hip flexion and potentially increase flexibility at the hip joint. Or, flipping it upside down, hip flexibility can be accentuated by body weight due to gravity when we’re in Child’s Pose. In both cases, we’re using an external source of leverage to explore hip flexion, rather than internal leverage from our hip flexor muscles.

Exercises that focus on mobility, on the other hand, bring a joint into active end range of motion (aROM) through internal leverage of muscle activation and coordination around the joint. This is what is often termed body control. For instance, pulling your knees into your chest in Apanasana without using your hands, or sitting up and attempting to pull your knees into your chest – both of these examples ask our hip flexors to generate force to explore the end range of motion in hip flexion.

Taking into account the difference between the above concepts and their definitions, I find it’s generally more beneficial to explore end range practices like yoga asana in a way that improves mobility, rather than just flexibility. In other words, I think it’s helpful to spend more time exploring end range actively than passively. This is because aROM is often more useful for how we move in accomplishing tasks in our daily lives, rather than just looking cool in a yoga posture for an Instagram photo.

But there’s more to it than just active versus passive—and to say one is better than the other always and for everyone would be a dichotomous and dogmatic belief. That, to me, doesn’t help understand the complexity of human movement and what each body needs to find balance. So in this article, I’ll explore how these two ways of exploring end range of motion—pROM vs. aROM, or flexibility versus mobility—are not opposites but are interconnected. We’ll also look at how controlling your end range (with aROM, or mobility) relies, at least in part, on your pROM, or flexibility.

To see how they are connected, for the purpose of this discussion, I’d like to expand our definition of mobility to include this more layered idea:

Mobility is the ability to explore end range positions without limitations in flexibility, strength, or coordination. Another way to think of it is that movement that displays mobility (over flexibility) displays a skillful balance of flexibility, strength, and coordination.

I like to think of these three sub-components of mobility—strength, coordination, and flexibility—as “seed” abilities.

Let’s deconstruct mobility further by taking a closer look at these three seeds in context using the pose Ustrasana, or Camel, as an example. Specifically, we’ll look at the shoulder mobility required for this pose.

Let’s say I’m having trouble with Ustrasana because I have limited shoulder mobility, meaning I cannot achieve enough range of motion in shoulder extension. We can use our three seeds of flexibility, strength, and coordination to explore why this limitation might be occurring, and how to address it.

Starting with flexibility, a passive end range of motion assessment could be one way to see if flexibility limits me in my ability to extend my shoulders.

If passive range of motion at my shoulders is not enough for Ustrasana, flexibility is the limiting factor. Remember that we always have more pROM than aROM. This means that what we can’t find passively, we definitely won’t find actively, either. In this case, flexibility might be a limiting factor because the antagonistic muscles that run across the front of my chest and shoulders don’t permit my arms enough freedom of movement to reach that degree of range in shoulder extension. I might feel “tightness” in that front part of my chest, which is a sign that my nervous system senses I’m moving into an unfamiliar position, and to not go any farther into this range.

However, if upon assessing my passive range of motion, I find that it is enough for Ustrasana, then lack of flexibility is not a factor—the limitation is more likely to be strength. The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) defines strength as “the ability to exert force.” In this case, the muscles of my upper back and the back of my shoulders that create shoulder extension are unable to produce enough force (i.e., active muscle tension) to overcome the forces acting as resistance. The forces of body weight/gravity, or antagonistic muscles and tissues that cross the front of my shoulders and chest, might be sources of resistance that my shoulder extensors are not yet strong enough to overcome.

Finally, let’s say that I have great enough strength and flexibility in shoulder extension for Ustrasana. However, I’m still having trouble controlling shoulder extension and the forces associated with creating that range in conjunction with what else needs to happen at surrounding joints.

This brings us to the third seed: coordination. Todd Hargrove defines coordination as when “different muscles and joints cooperate as a team to create a particular outcome.” FRC prefers the term control, or body control, to coordination. Lack of muscle coordination in Ustrasana might look something like this: from a tall kneeling position, I go to extend my shoulders, but before they even reach a mid-range degree of extension, my lower back begins to extend, too, creating some uncomfortable sensation there. Because I can’t keep specific segments of my body stable—in this case, my lumbar spine—while other parts move—my shoulders—the whole movement becomes poorly timed and poorly distributed across my body.

This illustrates an interesting paradox of mobility, which is that mobility depends on stability. In this case, we can think of stability as the ability to prevent unwanted movement. We will not be able to move from a specific joint if we can’t first prevent or control movement from the joints that surround it.

As a student, when you’re practicing alone, it can be hard to know what is or isn’t coordinated. Your perception of yourself from the inside is limited, so having an outside eye—a teacher, or even watching yourself on video—can be incredibly illuminating. This is especially important when addressing coordination since, without stability, attempts to improve strength and flexibility won’t be as effective. If every time I try to extend my shoulders using a chair or a wall, per the earlier examples, my lumbar spine picks up the slack, I’m not working on shoulder extension to the degree I could be. A teacher with a trained eye and skillful teaching strategies would provide feedback and ideas to help me stabilize my trunk, so I can more fully mobilize my shoulders. With this guidance, I might have a keener sense of body awareness to do the pose with more skill on my own.

To summarize, the more passively we work on improving mobility, the more we tend to be working on flexibility rather than strength and coordination.

And while passive work doesn’t focus on the other two seeds of mobility—at least not as much as active work does—that doesn’t mean there aren’t upsides to passive stretching. Often when we passively stretch, we are exploring a sensation of tightness. Tightness, or a perceived lack of flexibility, might be a response from our nervous system due to a lack of familiarity with a particular range of motion. Let’s say I spend most of my time sitting in a chair typing on a computer—not a lot of shoulder extension happening there. So when I go to practice Ustrasana, I might feel “tight” in my shoulders, and it may (or may not) have anything to do with the passive structures involved in that movement. My nervous system just isn’t familiar with it, so it gives me a warning: we don’t do this.

In this case, passive stretching would be one way to help me get into Ustrasana with more skill and ease. By slowly familiarizing my nervous system with this new range of motion, and evolving it over time, we might expand the “edge” of what we perceive as stretch in the shoulders.

Additionally, and this is not a small point, some people just like passive stretching—they feel good during and after a nice long stretch. It brings about a certain effect on their nervous system that helps instill a more balanced feeling in their body. For me, passive stretching offers me an energetic or perspective shift that’s a nice balance to the rest of my life, when I’m feeling overworked, externalized, and too active.

Passive stretching is a moment when I can internalize my awareness, and be more than do.

On the other hand, working actively involves all three seeds of mobility, and it is where I encourage students to spend more of their time in their movement practices. That’s because active movement is more likely to promote strength and coordination. Being able to control our movements is how our practice can help us more in daily life. So rather than demonstrating an extreme range of motion—so you can post your Ustrasana on Instagram—maybe active work improves the mobility in your shoulder extension in Ustrasana and makes it easier to reach into the backseat of your car for the snacks you left there.

When considering the benefits of working on flexibility and mobility, and how they’re different, it’s also helpful to remember that they are not opposites. Rather, we should view passive and active movement in context, which will require a more nuanced view of them. To do this, we could think of them as existing along a relative spectrum.

For example, in the image below, you might think I’m in a pretty passive backbend position, lying over the props. What you can’t see is that I’m pressing the tops of my feet into the floor and actively working to posteriorly tilt my pelvis and extend my thoracic spine. The pose looks passive, but depending on how much effort I apply, it is more active than if I were just lying there. The degree to which it is more active is relative to how much effort I apply in pressing, for example, my feet down into the floor and engaging my glutes.

Active or passive means something different to different individuals and their specific circumstances as well. A physical therapist would not give a stroke patient the same type of mobility work as a trainer would give a professional soccer player. Perhaps the most active practice for a stroke patient in improving their mobility in hip flexion would be to lie supine and attempt to pull their thigh toward their chest with the assistance of a physical therapist. A professional soccer player might improve their mobility in hip flexion by hanging from a pull-up bar and pulling one thigh to their chest (maybe even with chains and weights attached to their leg). These are both mobility practices relative to the individual, even though one requires a lot higher muscle force production than the other.

We could also zoom in on a spectrum of what passive might mean in the context of yoga propping and assists. For example, in a strong adjustment, a teacher might impose a large percentage of their body weight on a student to leverage their joints into a given position, meaning that the student explores a range of motion quite passively. However, with a light assist, a teacher might provide gentle pressure to guide a body part in a particular direction, or offer partial support of a limb where the student still has to do some of the work. In the latter example, the range of motion the student explores is active along a spectrum, but not as active as it would be without the light assist from the teacher.

The use of props is similar. Think of a pose like Utthita Hasta Padangustasana. Imagine how it feels to hold the lifted leg’s foot with a belt, which offers a certain amount of external leverage, versus clasping the big toe with “yogi toe lock,” or resting the foot on the back of a chair or pressing it into the wall. None of these are entirely active or passive—some are more passive than others on a spectrum, but all of them will ask us to do some work to maintain the body position.

Now that we know about these multiple factors contributing to how we explore mobility, we can begin to understand why having a lot of tools in our toolkit, and not demonizing certain approaches (specifically the passive ones) will keep our potential as teachers and students vast, supple, and evolving. Despite the efforts of marketers, we can’t simplify something as complex as human movement into a single, universal strategy everyone can buy into and benefit from. The truth is, everything works, some of the time, and every individual, their unique needs and preferences, are different. In the next article, I’ll show some more specific strategies for working on Ustrasana based on these principles, so that you have more practice options you can apply to help your students improve their mobility.

Edited by Jaimee Hoefert and Jordan Reed

Featured illustration by Ksenia Sapunkova | kseniasapunkova.com

Photos by the author

Enjoyed reading this article? Consider supporting us on Patreon or making a one-time donation. As little as $2 will allow us to publish many more amazing articles about yoga and mindfulness.