There is a buzz in the yoga community that our beloved yoga practice may be missing a few key ‘movement nutrients’ (thanks, Katy Bowman) to truly be considered “whole-body”. A whole-body movement practice is one that strengthens all muscle groups equally, promotes heart health, improves bone density, and prepares our body for functional movement (i.e., the movement that comprises our everyday activities). Humans have evolved to move in so many ways that it is difficult for a single activity to meet every requirement for a whole-body practice. This is why variety is key. That said, it is important to understand where your practice excels and where it fails so you can compensate for the missing nutrients.

Yoga, for one, does very well in the “pushing” category (think: push-ups, arm balances, handstands) while failing to incorporate “pulling” movements (think: rowing, pull-ups). Pushing and pulling are antagonistic movements in that they train opposing muscle groups. Muscular imbalances develop by overtraining one muscle group while undertraining the opposing group. Countless studies have demonstrated how muscular imbalances predispose individuals to injury1–5. In this article, we will take a look at two prime examples of yoga’s missing movement nutrients – pulling and/or grip strength and sufficient posterior chain work. (This is by no means be a complete list of yoga’s missing movements.) Then we will show how you can remedy these shortcomings.

Pulling

Yoga infamously fails to train one integral functional movement: pulling! While we push to our heart’s content with the enumerable chatarungas (i.e., low push-ups) and arm balances, it is very challenging to train our pulling muscles on a yoga mat without equipment. Sure, poses like padanghustasana (standing forward fold with peace fingers on big toes) and paschimottanasana (seated forward fold with hands grabbing feet) have a ‘pulling’ action. The amount of load being pulled, however, is pittance compared to the load being pushed during a chatarunga. The easiest way to avoid developing muscular imbalances and to balance all the pushing you do in your asana class is to get cozy with a pull-up bar.

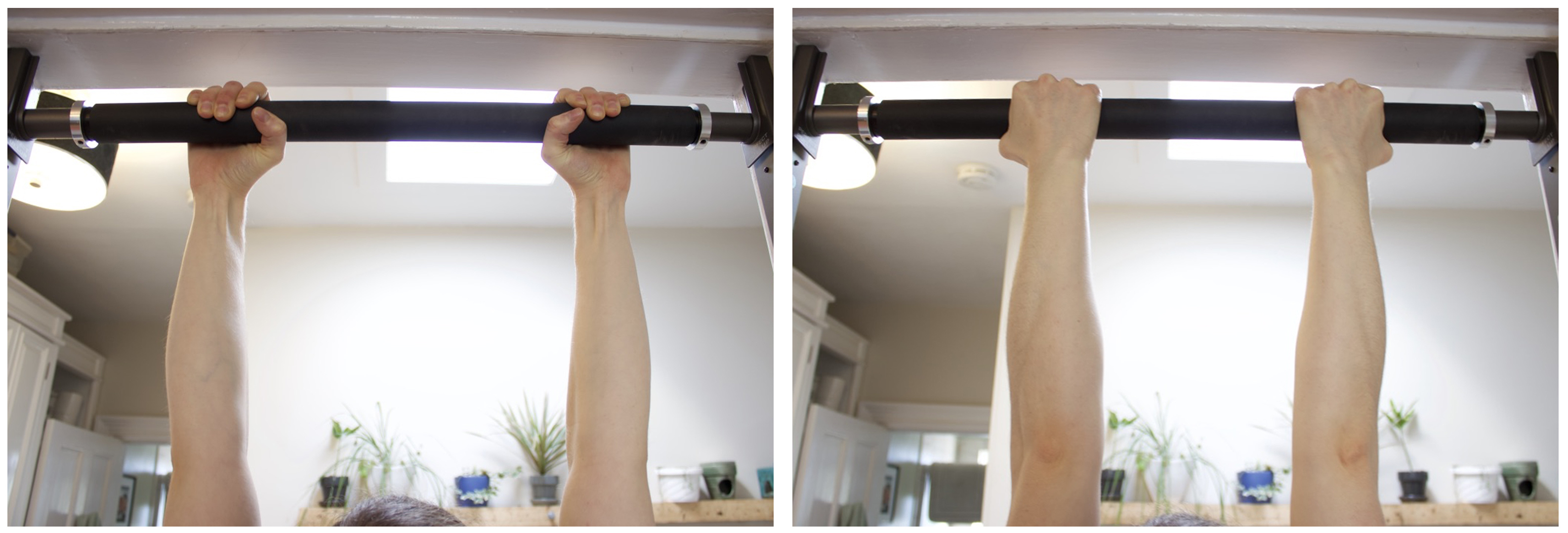

Try it yourself: Passive and Active Hangs

For a passive hang, grab hold of a pull-up bar with a grip slightly wider than shoulder width. Keep your arms straight and strong and pull your shoulder blades together and down your back for an active hang. Time yourself and determine how long you can hold both passive and active hangs. Eventually, increase the time you can hang. Movement enthusiast Ido Portal recommends hanging for 7 minutes a day. Begin with a modest goal of, say, 1 minute and work your way up.

Try it yourself: Body Rows

Lower your pull-up bar to about chest height. Grab a hold of the bar and position your body on an angle relative to the floor. The exercise is easier when you position your body more vertically and harder as you position your body closer to parallel with the ground. Draw your shoulder blades together and down to activate the muscles in your back. Flex your elbows pulling your chest up to the bar. Repeat for 8-12 reps. Do this set 3 times.

Grip Strength

Incorporating exercises on the pull-up bar has the added advantage of improving your grip strength — another neglected movement in asana. Grip strength is imperative during functional movement (think: opening sticky jars or carrying heavy groceries). Because grip strength is required for the pulling exercises discussed above, training it will make that ever-elusive pull-up an easier feat. Grip strength trains the muscles in the forearms and hands. Even your handstand practice will benefit as your wrists will be stronger and more mobile!

Try it yourself: Vary your grip during pull movements

Vary the grip on the pull-up bar during any of the pulling exercises outlined above. Varying your grip allows you to comprehensively target all the muscles in your upper arms and forearms. The overhand (i.e., pull-up) grip will more effectively target the forearm flexor brachioradialis while the underhand (i.e., chin-up) grip will more effectively target the biceps.

The Posterior Chain

The posterior chain is a fancy term for the muscles of the back body (e.g., back muscles, hamstrings, glutes, biceps etc.) There are many yoga poses that strengthen the posterior chain such as locust pose, wheel pose, upward facing dog, or reverse table/plank. Unfortunately, the frequency with which these poses appear in most sequences is disproportional to those that target the anterior chain (e.g., quadriceps, abdominals, chest muscles, triceps etc.). Further, it is easy to cheat our way into many back-body strengthening poses rather than performing them with maximal strength. Thus, even though we do perform poses that are meant to strengthen the back body, we don’t always get the most out of them.

Take, for example, upward facing dog. Up-dog asks us to contract the muscles of the back to open the chest and engage the legs and glutes to extend the hips. That said, it is also possible to express this pose by hanging out in the foundation of the hands and feet without asking much from posterior chain. Locust pose, to the contrary, is much harder to cheat your way through. Because the hands and feet are no longer planted as the foundation, our ability to lift our chest and legs requires engagement through the back body. In the following Try It Yourself box, you will see how establishing a mind-muscle connection in locust pose can remind our bodies how to find strength moving into upward-facing dog.

Try It Yourself: Upward-Facing Dog versus Locust Pose

Perform locust pose with the feet planted. Lie belly down on your mat with your arms along your sides. Inhale to lift your chin, chest, and arms. Don’t use momentum — feel your legs, core, and back body engaged. Exhale to lower back down. Repeat this movement three times. Now that you have established the mind-muscle connection with your posterior chain, move into upward-facing dog. Plant your hands by your lower ribs, roll your shoulders down your back and press firmly into your hands and the tops of your feet to lift your chest and hips. Don’t just hang out in the pose; really activate your legs, core, and back body like you did in locust pose.

The Hamstrings

The hamstrings can be difficult to strengthen in asana. While we do find poses that use the hamstrings — a typical asana sequence disproportionally strengthens the quadriceps and stretches the hamstrings. Many yogis find that hamstring-dependent movements cause their muscles to cramp because they have not been accustomed to hold tension.

Try It Yourself: Are your hamstrings scared of tension?

Come into a low lunge position with your hands planted on the inside of the forward foot (like a dragon pose). Flex your back knee to bring your back heel into your glute. Squeeze your hamstring to drive the movement and bring your heel closer to your bum. Your hamstring might cramp here. If so, your hamstrings are not used to holding tension.

Regardless of whether or not your hamstrings cramp, because we spend so much time in yoga stretching the hamstrings and strengthening the quadriceps, it might be time to incorporate some more hamstring work into your movement practice. Healthy muscles are both strong and flexible so it is important to balance all the flexibility training with strength training. Here are some easy ways to strengthen the hamstrings on your mat — both your hamstrings and your glutes will thank you! The hamstrings and glutes work together to drive hip extension. Thus, exercises involving hip extension trains both the hamstrings and glutes.

Try It Yourself: Plank Leg Raises

Come into a high plank position. Keeping the legs straight and strong. Lift (extend) one leg then lower it back down. Repeat for 8-12 reps then switch sides.

Try It Yourself: Malasana to forward fold

Come into malasana pose or deep yogi squat with your arms stretched out in front. Keeping your belly resting on your thighs, slowly begin to straighten (extend) your knees eventually ending in a forward fold with your fingertips touching or reaching for the mat. Don’t worry about straight legs here. Repeat for 8-12 reps.

Now that you are well acquainted with the muscles of the back body, try the following three exercises that strengthen and mobilize the entire posterior chain in a dynamic and functional way.

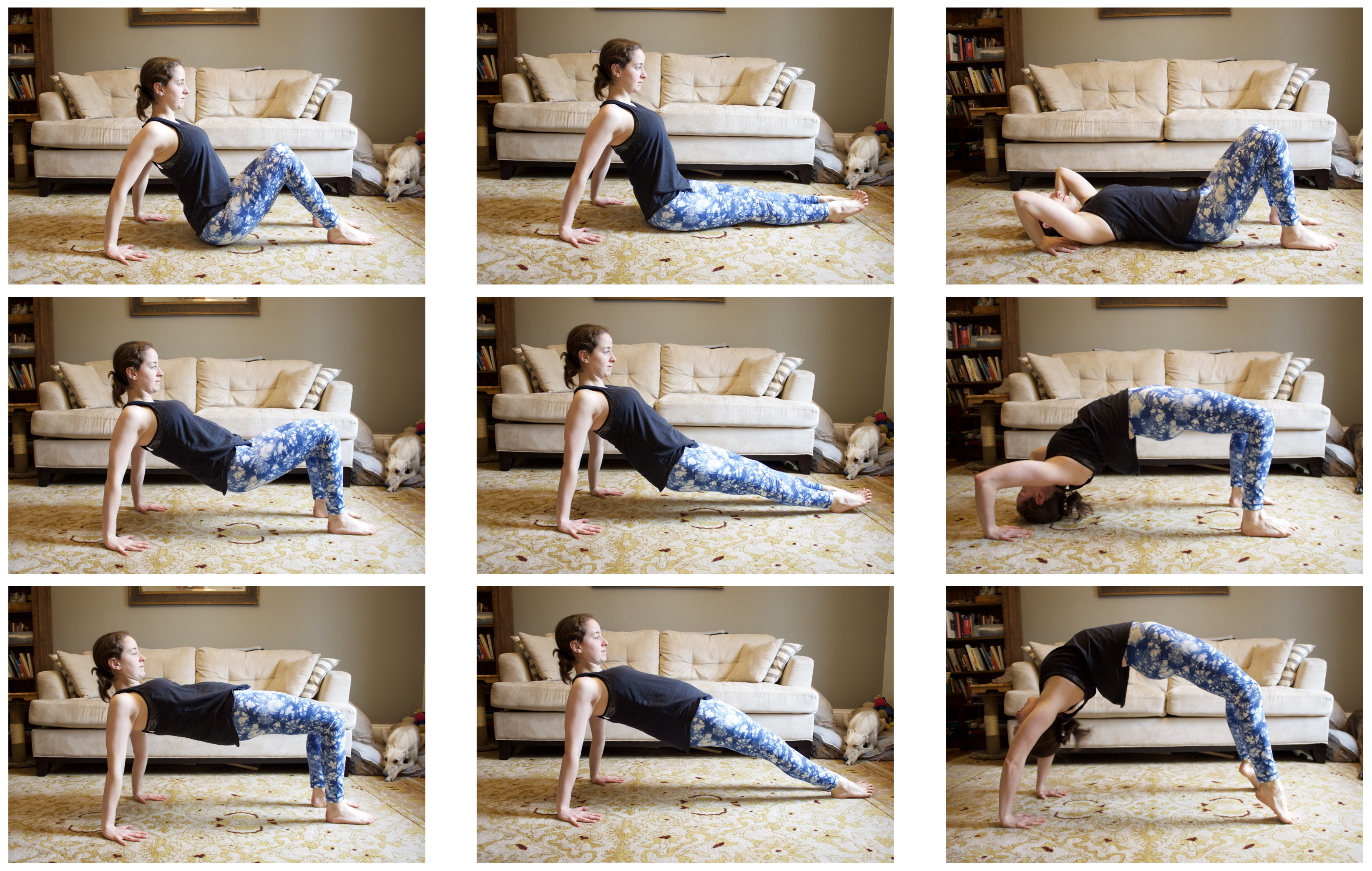

Try It Yourself: Reverse-table, reverse-plank, and wheel push-ups

Perform reverse-table, reverse-plank, and wheel pose in repetition (i.e., as push-ups). Once you are comfortable with the first exercise you can work your way up the progressions. Aim for 8-12 reps.

Balance Your Practice

In this article, we looked at two prime examples of missing movement nutrients in a traditional asana practice. We have seen how yoga can be limited in its ability to train the posterior chain and the muscles involved in pulling. We have also seen how easy it is to remedy these shortcomings by emphasizing specific movement patterns and perhaps familiarizing ourselves with a pull-up bar. Regardless of what your practice entails, it is important to assess where it shines and where it fails to deliver all the nutrients required for a balanced movement diet.

References

- Knapik JJ, Bauman CL, Jones BH, Harris JM, Vaughan L. Preseason strength and flexibility imbalances associated with athletic injuries in female collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(1):76-81. doi:10.1177/036354659101900113.

- Wang HK, Cochrane T. Mobility impairment, muscle imbalance, muscle weakness, scapular asymmetry and shoulder injury in elite volleyball athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2001;41(3):403-410. doi:10.1055/s-2001-11346.

- Hadzic V, Sattler T, Veselko M, Markovic G, Dervisevic E. Strength Asymmetry of the Shoulders in Elite Volleyball Players. J Athl Train. 2014;49(3):338-344. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-49.2.05.

- Croisier J-LL. Muscular Imbalance and Acute Lower Extremity Muscle Injuries in Sport. Int Sport J. 2004;5(3):169-176. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/58123. Accessed January 27, 2018.

- Croisier J-L, Ganteaume S, Binet J, Genty M, Ferret J-M. Strength Imbalances and Prevention of Hamstring Injury in Professional Soccer Players. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1469-1475. doi:10.1177/0363546508316764

Illustration by Katya Uspenskaya

Enjoyed reading this article? Consider supporting us on Patreon or making a one-time donation. As little as $2 will allow us to publish many more amazing articles about yoga and mindfulness.