Inhale cow pose, exhale cat pose. Inhale raise your arms overhead, exhale fold over your legs. Inhale up dog, exhale down dog. Inhale lengthen the spine, exhale twist.

These cues—couplets of breath and body—implanted themselves in my brain as a new yoga teacher. I remember huddling around a sticky Formica table at a cafe in midtown Manhattan with my fellow trainees (those were the days…) working hard to commit the instructions to memory. Of course, we wanted to pass our exam, but we also wanted to make sure we were teaching yoga the “right” way. Long before I began training, I’d been lulled by these rhythms in the vinyasa yoga classes I took several times a week, my teacher’s voice seeming to summon a natural dance between my gross and subtle selves.

It felt so good to be able to rely on what seemed like an inviolate, absolute way of being—working with the natural urges of my body, rather than against them, like so many forces in the world encouraged—that I rarely stopped to think about the reasoning behind the pairings of breath and movement that had seduced me. Even as a trainee, they were points to memorize rather than to really understand. One or two of my more creative teachers would occasionally change things up, asking us to breathe out of pattern, but my breath inevitably fell back into the ingrained rhythm, almost as proof that there was a rightness to inhaling into extension, and exhaling into flexion.

With our understanding of the way asana fits into the full spectrum of a yoga practice, how Western culture has appropriated and modified the original teachings, and everything about life coming into question these days—and a lot more time to do my own thing on my mat—I recently decided to dive deeper into the breath patterns that had brought me so much comfort in the past. A frightening virus had begun running rampant through the airways, nasal passages, and lungs of our world; my devices continually circulated images of people being robbed of their breath for no reason other than their skin color; and daily panic attacks robbed me of oxygen and mental stability—all of which made breathing a new source, and result, of the anxiety I was facing. I suddenly felt an urgent need to become more intimate with it than I had been while memorizing cues for a test, or occasionally checking in when I decided to do pranayama for three minutes after savasana. I couldn’t just do what I always did, because nothing about my life or how I felt in my body was the same. I needed to feel into the way my breath created spaces within my body and mind for exploration and, ultimately, the surrender to the unknown that is at the heart of the yoga practice.

Through experimentation, challenge, and unlearning of what I thought I knew, I have been examining why and how the breath-body works together on both physical and energetic levels. I focused my self-study on a pair of postures that are often quite rigidly taught “on the breath”: forward folds and backbends. In these end ranges of movement, I discovered the impossibility of separating the body and the breath (from each other and from everything else), of expecting that any movement could have just one origin point or one outcome. While the in-breath and out-breath, like backbends and forward folds, are counters to each other, they are both, always and inevitably, reinforcing the center of our being that is the primary inquiry of this practice. We can visit the peripheries of our experience with curiosity and joy only when we know there is a base to return to; and by reinforcing that base even in counterposes, we can experience ourselves in a nondual, holistic way.

Feeling the breath in this way helped me access a fuller state of being alive—gross and subtle, soft and strong, dark and light. This, more than anything about respiration, has been one of the most comforting discoveries I’ve made since the pandemic. In what follows, we’ll dive into the steps of this journey—the anatomy of breath, and how to play with it in these two sets of postures, as well as why we might choose one way of breathing over another.

Breathing 101

Even though we all breathe all day, every day, it’s usually automatic, and thank goodness! If we had to think about and consciously direct our breathing we wouldn’t get much done. So let’s take a pause together to review this fundamental aspect of our existence, including the mechanics of this unconscious process.

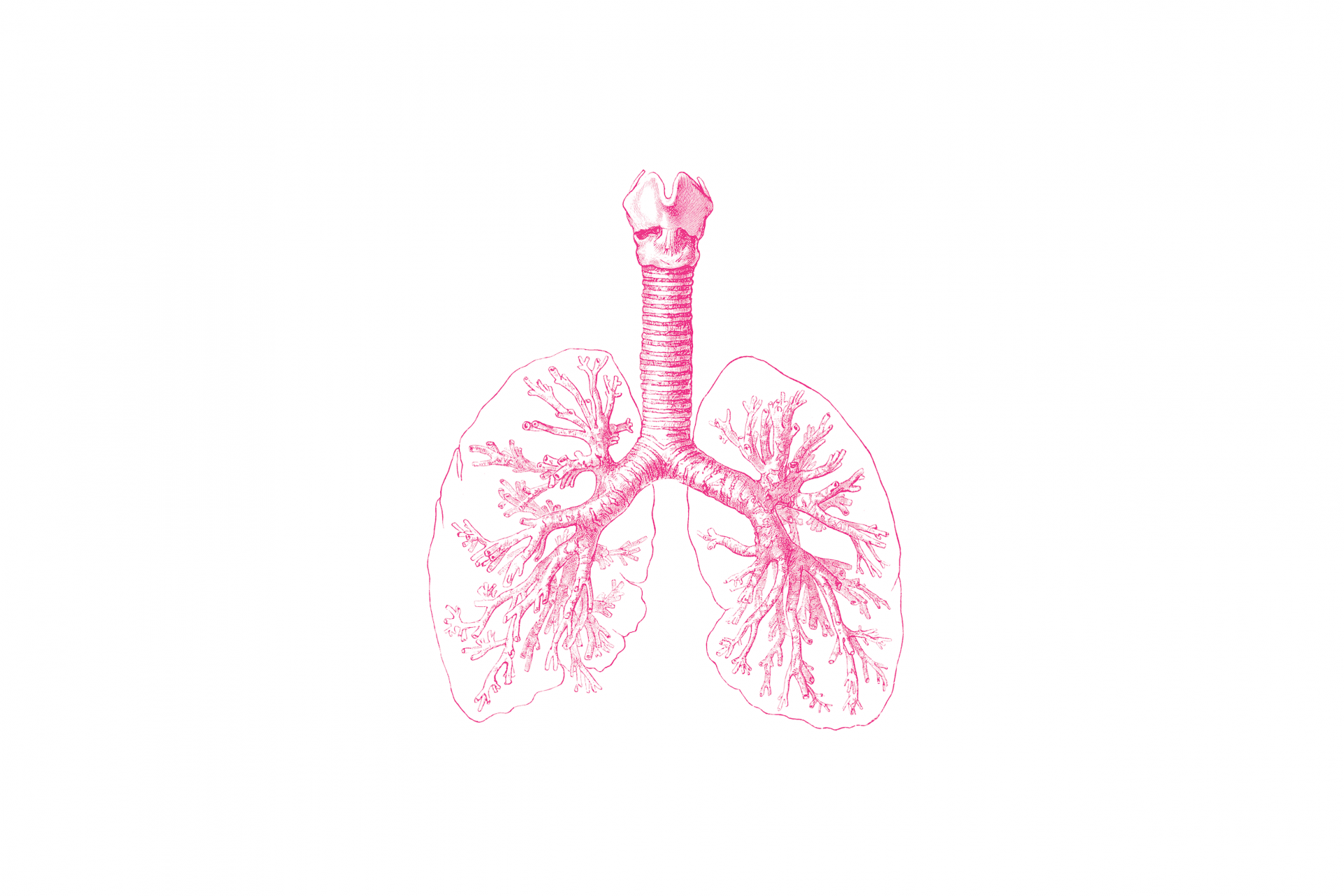

Breathing all starts in the diaphragm—a large muscle below the lungs, right around the solar plexus or center of the torso. In its relaxed state, the diaphragm curves upward, like the dome-body of a jellyfish. As it contracts, the muscle shortens and moves downward into a flatter, horizontal-ish shape. If that mechanism is as contradictory-seeming for you as it was for me when I first learned it, check out the illustration below:

The diaphragm’s raised, domed, relaxed state occurs on the exhalation phase of your breath; on the flip side, the flattened and taut contraction happens on the inhalation. You can feel this mostly in your abdomen, since that’s where the ebb and flow of the diaphragm moves things around. When you inhale, and the diaphragm lowers so your lungs can fill (widening the cavity of your chest), and the contents of your guts also need to go somewhere to make room. That somewhere is usually out, i.e. “breathe into your belly,” and your stomach puffs out. When you exhale, the opposite happens: as the diaphragm lifts back up, the abdominal contents shift back into place, and the lungs shrink down as the air that once filled them moves up and out—like squeezing toothpaste from the bottom of the tube.

Of course, this choreography involves more than just your lungs, diaphragm, and abdomen. Everything we call the “core” gets to play when we breathe, and lots of other processes are happening to ensure that the air you take in delivers oxygen to your whole system. There’s also an interplay between ourselves and the external environment driving the entire process, since our breath is basically responding to changing degrees of pressure in our bodies compared to the atmosphere. But for the purposes of this article on balancing the counterposes in our movement practice, this action of the diaphragm is where we’ll focus.

Breathing and Movement

Given all of the simultaneous actions happening every time we breathe, it makes a lot of sense that the positioning and movement of our entire body’s anatomy—in regular life or in a yoga pose—will affect our breathing, and vice versa. More than just the gross movements we focus on in yoga asana, we can also consider how the movements of the subtle body are implicated in breath. Ayurveda, the sister science of yoga, describes five primary movements, or variants of the air element, known as vayus, that go beyond just the physical body. The vayus affect almost every function of our body, mind, and experience in the world, from digestion and elimination to memory and sensory perception. Two of those five are most clearly linked to the breath: prana vayu and udana vayu. You’ll probably recognize the former from pranayama; it’s the down-and-in movement that corresponds to inhalation (among other things). Udana vayu moves up-and-out, like your exhalation.

Besides their basic directionality, what’s important to note about these vayus is their energetic effects on our systems. Prana vayu (and another vayu called apana, which moves down and out—similar but different) engenders a feeling of grounding, fullness, and stability. It functions properly and completely when the nervous system is in the parasympathetic or “rest and digest,” mode. Udana vayu, on the other hand, is much more destabilizing. It aligns with the sympathetic nervous system, which is evolutionarily essential to our survival (think: running away from danger and, of course, exhaling). But not every element of the sympathetic nervous system is meant to be turned on all the time, as it often is in our daily, stress-filled, and now pandemic-and-social-unrest-filled, lives. Udana goes against the natural order of things (gravity draws things downward), which is why when there’s a lot of upward movement (think racing thoughts or hyperventilation or reflux or vomiting), we say we feel “off.”

To review: prana = inhale = grounding; udana = exhale = stimulating… Wait, what? That’s not what I was taught in YTT, and it certainly isn’t how I usually experience backbends and forward folds in their traditional breathing patterns or energetic effects. Maybe you’re also confused, but before you stop reading, consider this: all the vayus are needed for our survival, just like both sides of the breath. So, what if the counterposes also contain an element of nonduality, of bothness? What if we could experience the union of opposites even in the extremes of our movement? What if at the core of it all was a trust in stability, from which we can take risks and open our hearts to new experiences? Now, that’s the kind of yoga I’m interested in—and the kind of yoga I’ve been needing lately more than ever.

Inhale, Extend

Now that we have those basics on the table, we can get into what this means for our asana. Let’s start with the inhalation—the diaphragm contracting and lowering, and prana vayu moving in and down. In yoga asana, inhalations are often cued in postures involving extension of the spine, better known as backbends. Urdhva hastasana, cow pose, salabhasana, ustrasana—the whole gang.

This pairing makes anatomical sense in a lot of ways. If we focus on the movement of the pelvis in a backbend into an anterior tilt (which in my opinion is even more interesting and crucial than the spine itself), we have prime conditions for a proper, deep diaphragmatic breath—or maybe, the diaphragmatic breath is what creates the conditions for the backbend. When the lumbar spine moves into extension, the frontal hip points seem to spread apart, making more space for your descending guts; the inner thighs spiral inward in a way that encourages the pouring down of the breath as the diaphragm lowers, like a drill bit spiraling into the core of the earth; the creases of the groins deepen, slackening the psoas muscle and allowing for a parasympathetic response in the nervous system.

Prana and apana vayu are also very happy in this position, which per our earlier discussion means a feeling of grounding, heaving, and generally downward energy. And yet backbends are often associated with upregulating qualities (at least that’s what my YTT manual said), and in experience this might even be true. I think of the head rush I feel coming out of bridge or upward facing bow pose, the way my emotional heart feels lighter, my pecs more open after collapsing in front of screens all day, when I allow the front of my chest to expand and turn upwards in a backbend. Depending on what you’re doing, inhaling will also stimulate the sympathetic nervous system; think about the rapid gulping of air of a runner or someone having a panic attack, and you’d see how this phase of breath is anything but grounding.

So what gives? How come we breathe in, a downward (but sometimes upward) energy, when we extend the spine, an expanding energy? The two are not as opposed as they may seem—and even their contradictory qualities are essential to why they’re coupled in a yoga practice, which the Yoga Sutras explains as the union of opposites. We root to rebound, a common phrase that has as much anatomical relevance as it does energetic. We allow the pelvis to tilt anteriorly in a backbend, but bring in elements of posterior tilt (i.e., a forward fold) to bring a sense of “neutrality.” Going back to the physiology of a backbend, that looks like encouraging counteractions to create stability in the uber-mobile lumbar spine. If the inner thighs want to spiral inward, we engage the muscles in the glutes and legs to encourage external rotation. If the pubic bone wants to lower and bring the pelvis into anterior tilt, we draw the tailbone down so the sacrum doesn’t scrunch.

In terms of our breath, this spaciousness in the lower body creates the condition for the inhalation to be full, where the diaphragm completes its contraction, and hence is actually relaxing and grounding rather than destabilizing. From that container we can move into extension with support from prana and apana vayu, and a supple and unpanicked diaphragm—body and mind stay relaxed. That posture ensures that the base of the spine (at the sacrum) remains wide and soft, thus avoiding the all-too-common complaint about backbends, that they result in back pain. It’s another kind of subtle counteraction that helps us to experience the expansiveness and bravada of the backbend without losing our grip on the way our bodies work.

The humility and interdependence of the root-rebound relationship is where backbends will allow the heart to truly open. Since our chakras are located all along the spine as well, a grounded backbend will also stimulate those energetic wheels, especially around the third chakra, or solar plexus. The seat of our ego (and aligned anatomically with the diaphragm), this cluster of nerves is a hub of vital information that is all too easy to ignore when our spiritual hearts are blocked or caged off, from stress or fear (aka, life in the 2020s). By allowing gravity to draw us toward the earth, like a longing for connection, we can explore independence and freedom and space all along the front body knowing that something has our back.

Exhale, Fold

For me, forward folds are one of the highlights of the end of a yoga sequence—the part where I get to sit down and stop working so hard in my arms and legs. I remember in my early years of practice, I’d know that savasana was just minutes away when the teacher got us through the backbends (the last “push,” she’d say), then brought us into paschimottanasana, which thanks to my dancer flexibility came relatively easy for me. In YTT, I learned there was a reason for this sequence: the two kinds of postures were “counterposes,” said the manual, since the spine was in opposite ranges of motion and therefore balanced each other out, the way you can bend a folded piece of paper back and forth along its crease to flatten it out.

Because of their somewhat passive orientation, forward folds are often considered “relaxing”—another counter to the “energizing” backbends—and indeed they can be. With the head below the level of the heart (or moving in that direction), the nervous system starts to shift into parasympathetic mode (aka savasana-land). Breath-wise, forward folds are also often done on the exhalation, another parasympathetic gesture. That works out well in our bodies, since when the abdomen retreats back toward the spine as the diaphragm lifts, there’s literally more space for us to move our torso toward our legs. (If you’ve ever done forward folds with a stomach full of food or drink, you’ll know how uncomfortable it feels to not have that space.) We’re also primed to “turn the gaze inward,” a cue I’ve often given in class, in preparation for final relaxation.

At the end of a stronger, more active yoga sequence, or even after those stimulating backbends, this energy can be extremely useful; it’s also quite delicious when the nervous system is heightened for any reason, such as transitional seasons of life like new jobs or relationships or social structures; or the fall and winter seasons when air and space elements are at their peak, creating chaos and disorder and decay all around. Fun times—let’s all just flop over and call it a day, right?

But given what we know about the not-black-and-white dynamics of the breath in the body, and the energetic and anatomical features of forward folds’ counterposes, let’s avoid jumping to conclusions about pure relaxation in these shapes. In my experience, I don’t think anyone would argue that folding over legs with “tight” hamstrings is exactly relaxing. I’ve seen students break out into a sweat in ardha hanumanasana, even when using several blocks under their hands for support; and I myself have been put on high alert when stretching the backs of my legs in response to an old injury that my body was trying to be protective of.

So let’s take a step back and think about just how forward folds actually appear in a yoga sequence, how they are generated in the body, and how they feel. In addition to the stimulating contexts above, forward folds are incorporated throughout a standard vinyasa sequence in a way that requires a good deal of strength and attention, not just passive flexibility—think uttanasana, or standing forward fold, the second pose of the sun salutations. The passive version of forward folds might feel good for a few seconds, especially when we’re tired and tight, but that’s only increasing those same qualities in our bodies, not balancing them. And when we move from that state, especially in very mobile areas like the lower back, we’re setting ourselves up for possible injury because those mobile joints aren’t supported. Who wants their yoga practice to make them feel worse? Not me.

Forward folds can be quite stimulating along the back chain of the body—the spine, the sacrum, the hamstrings, the legs, and even the feet. They wake up this incredibly powerful and stabilizing channel that, because we’re such forward- and outward-facing creatures, is often neglected in our day-to-day lives and postures. This is the quality of udana vayu, the exhalation kind of air element, that needs prana in order for us to stay in the feeling of our bodies. We can’t exhale without something to exhale; we can’t expect our backside to open up if it has no confidence in its strength.

Approaching forward folds with the intention to ground and stabilize, then, might be one way to yet again have our yogic cake and eat it too—to be relaxed and open, to let the back body lengthen as the front body contracts, while channeling the opposite. The breath helps us out with that, even if only in the form of a visual. Breathing in creates space and fullness in the lower body (legs/pelvis/spine), and we can imagine preserving that essence of space when we move into a forward fold even if the breath is leaving the body. With a wide, full-feeling lower back and sacrum, there’s less of a chance of straining the soft tissue that connects the pelvis and legs (aka, the hamstrings). As a result, the spine can stay in its natural curves as well, preventing the common rounded position we see in postures like paschimottanasana. At the same time, the descended position of the diaphragm, and anterior tilt of the pelvis, that happens with the inhalation actually assists the lengthening of the hamstrings you are going for in a forward fold, meaning you don’t need to force yourself into the pose by tugging or pushing.

The Both-And Approach

The way I’ve described the effects of the breath here is just one interpretation and application of the powerful synergy between breath and body. There are certainly instances where you’d want to breathe in on a forward fold, or breathe out on a backbend—even if just for curiosity’s sake. Our resilient bodies are not so delicate that the pairing of postures and respiration requires a lot of awareness; if they did, we wouldn’t last very long!

What’s more interesting to me as I played around with these dynamics is remembering that my yoga practice, on every level, cannot be reduced to a single goal or effect or set of actions. There will always be stability with mobility, relaxation with stimulation, exhalations with inhalations. It’s a powerful reminder that when I start to veer too far in one direction—in my body or in my mind—there is always a counterpose to bring me back to center. Making peace with the fact that the center will never be fixed, that the equilibrium between opposites is a constantly moving target, and that my practice will allow me to adapt to those changes is what keeps me curious and excited to come to my mat as a teacher and as a student. I may be familiar with postures and sequences, but my response to them is always surprising and mysterious.

Edited by Jaimee Hoefert & Ely Bakouche

Photos by Jennifer Kurdyla