“And now, pay attention to your breathing.. Breath is portable and the most intimate way we have of connecting to ourselves and our bodies.”

How often have you heard a phrase like that spoken in yoga class, or during meditation? How many apps and guided meditations do you think exist which make breathwork the priority practice?

It is true that our breath is a portal to intimacy. Our breathing space is a personal space and we each have our own relationship with breathing, which is informed by our experiences and emotions and might be different on any given day, or time, of our lives.

I have learned that we teachers and meditation guides should always be aware that some of our students and clients will not feel safe when guided into awareness of their breathing: they may have a trauma-relationship with breathing, they may be healing suffering related to being controlled, or they may simply have come to class to be in their own breathing space without being imposed-upon.

People have all sorts of reasons for coming to class and many of those reasons relate to their mental wellbeing. Recent data suggest that at least three-quarters of a yoga class will be populated by people whose reason for being there is to look after their mental wellbeing.

Because breath is so personal and intimate, those of us teaching breath practices need to recognise that we are in the territory of sacred, personal, and private space. There is a need to honour each person’s individual experience and relationship with breathing and tread carefully with our cues, space holding, and instruction.

Not everyone feels comfortable with breathing.

Breath practices are known to form the bones of many traditions within the wellness and spiritual spheres, including and especially yoga and mindfulness. Breath engages us with our bodies and can be very grounding. However, not everyone has the experience of feeling grounded when they pay attention to their breathing. Indeed, sometimes, people feel the exact opposite.

When I first started my meditation coaching practice a decade ago, I was taken aback by the number of clients who would ask me not to mention the word “breath” in my conversations and guidance and discovered from my colleagues in the space that this was not uncommon.

Many of my clients had experiences of fighting for breath – due to asthma or other respiratory problems, a traumatic experience, medical event, or anxiety – and paying close attention to breathing was highly triggering for them and counterproductive to finding the calm and relaxation they were hoping for in our sessions. Others had been conditioned into so much breath instruction, perhaps by their physiotherapist, meditation, or yoga teacher, that they associated breath with control and being controlled to a suffocating degree. This was a particular sensitivity for people with trauma histories involving being controlled or suppressed.

Over my years teaching in the wellness space, where I make it a priority to ask my clients, friends, students, and fellow teachers about their personal relationship with breathing, I have discovered that none of these is rare or unusual. Indeed, it is commonplace. More likely than not, in a space where one of the primary reasons people show up to classes is for their mental health, a significant number of students in each of our yoga classes may have difficulty accessing guided breathing practices safely and comfortably.

I certainly shouldn’t have been surprised when this arose in my sessions in those early days. I myself, like so many others, have had an on-off love affair with breathing during the course of my journey in embodiment.

There are mental and/or physical health reasons for finding the practice more harmful than beneficial.

(If interested in reading up on these experiences, I recommend Facebook support and research-based groups on meditation-related difficulties, which can give us a raft of both anecdotal and clinical data on such experiences.).

The sober truth is that while we are sitting happily in our teacher’s seat at the front of the class, guiding pranayama with the confidence that we are offering a beautiful experience of intimacy and ease, the very opposite might be happening. Unless our students give us their raw feedback, we can’t always discern this – meditation is, by definition, an “invisible practice” and unfortunately, shame at “not being able to do the practice” can inhibit our students’ courage to share.

I have met people who think of meditation and breathing practice as a performance that can be judged as “doing it correctly” or “getting it wrong,” invoking feelings of pressure or failure or self-rebuke. Even though no one is watching us on the inside when we are in inner-practice, it can feel like they are.

How then, do we set about addressing all our students’ desires to practice and explore freely and safely within their own bodies, while at the same time introducing them to the potential for healing and magic that arises when we find ways to become friends with our breath?

In this article, I offer some awareness about breathing and cues and practices to explore. I have developed these with my colleagues and clients who have shared their inner processes with me, for which I’m extremely grateful. I hope these might help you to access the range of wonderful experiences breathing practices can bring and share them in ways that enable others to have a positive and safe experience.

1. Pause for a moment and fully recognise the breadth of breath.

What is breath anyway and what does it mean to be “breath aware”?

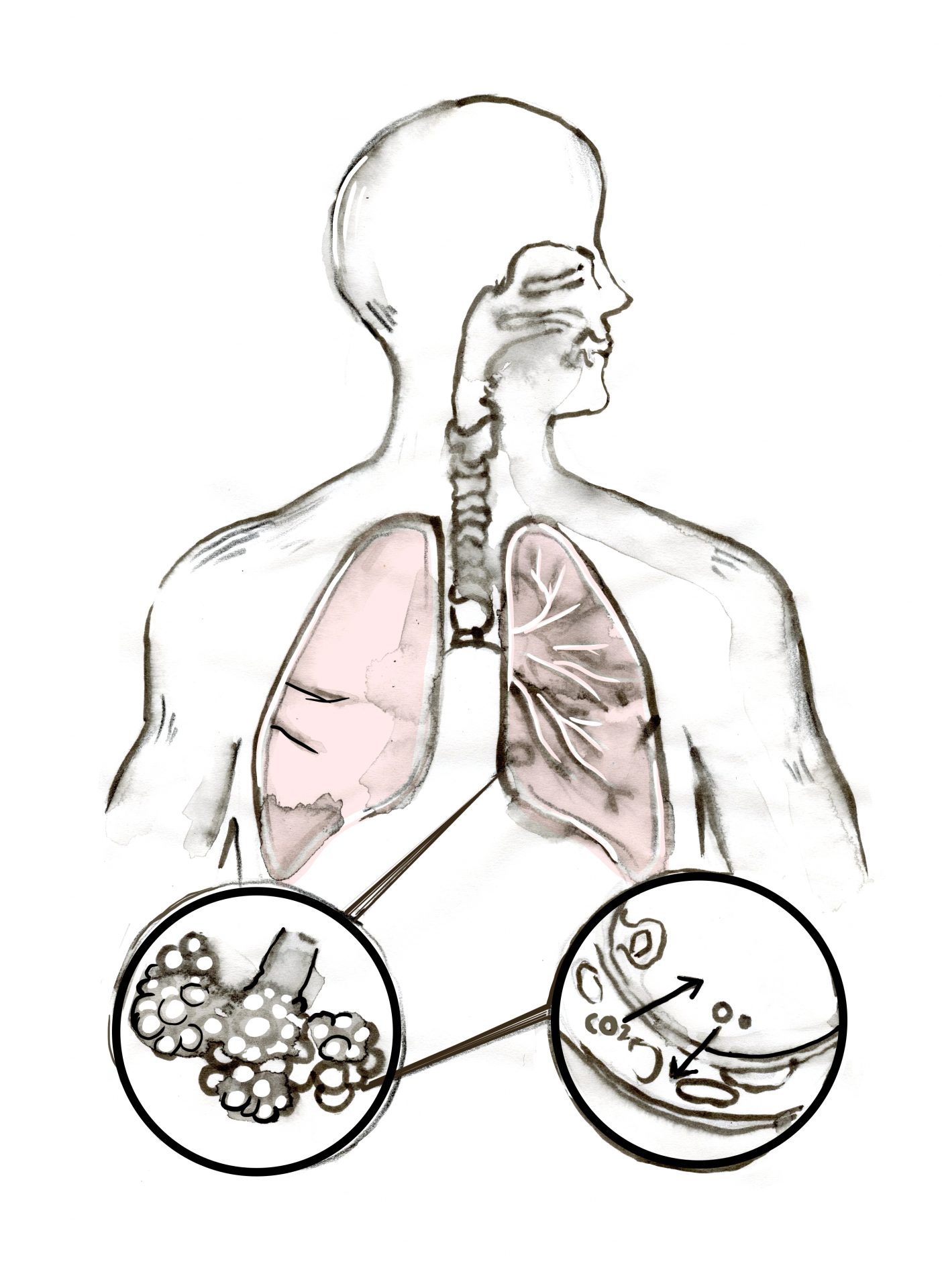

Physically, our breath is a source of nourishment, nurture, and healing. It is responsible for ensuring our body-mind functions at its absolute best. It is the lifeblood of our organs, including the heart that beats the rhythm of our lives, our digestion which gives us fuel to move and act, our livers which process toxins from our bodies and, importantly, our nervous systems which prime us for protection, action, and recovery, and our brains which are the assessors, processors, and expressors of our experience of our lives on Earth.

Metaphysically, our breathing is like the conductor of an orchestra – tuning our instrument (our bodies and our instincts) and weaving our body, mind, and spirit together into harmony and wholeness.

I invite you to pause for a minute and consider these truths:

- The air you breathe in is a personal gift to you from life, in the form of oxygen to nourish yourself. The breath you exhale in the form of carbon dioxide is your gift back to life. The exchange of energy you are involved in is between you and life, not you and a teacher – unless you invite them into your process.

- The air you are intimate with becomes, for a brief moment, a part of your own, private inner atmosphere. No one can breathe your breath while it is yours, except for you.

- Your breath has its own rhythms and expressions, guided by things that are personal to your body and your life. It is up to you how, when and if you explore other expressions of breathing in your own body

- Your breath is part of your bodily functions. You have a right to be given agency here.

2. Invoke the teacher’s best mantra: “First, do no harm.”

We are more able to meet whatever is arising in our awareness if we feel safe to do so. If we do not feel safe, we may dissociate from our bodies to avoid feeling discomfort. This can mirror the “flight” or “freeze” response to threat: as in those cases, we are retreating, hiding, or escaping. When we are anxious, it helps to be brought back into our bodies and into awareness of the present. Once a person feels safe to take their awareness to their body and their breath, we can continue to ask questions that help them enter a safe enquiry with themselves which itself activates changes and a movement towards homeostasis.

Whenever I prepare and deliver my teaching, I have a deep intention to abide by the principle of Ahimsa (non-harming).

I believe our first guiding principle, whether teaching a physical or metaphysical practice, must be “First, Do No Harm.” We can also offer this mantra to ourselves as a gateway to any of our personal practices.

I remember that it is an honour to be invited alongside another human being’s personal space and experience, even for a short while. I also bring this reminder into my personal practice. I remember that every human is individual and unique, and they may have any number of reasons for being in my class or coaching space. While I can hold space with spacious empathy and non-judgmental awareness, I cannot possibly know what it is to be any person other than myself. I don’t know how it feels to be living and breathing in their own body or how they are experiencing life right now. I remember that our best and most healing and liberating path is not to impose our practices on others or allow ourselves to be imposed upon.

I may not get it right every time and for every person, but the intention itself becomes a natural guardian. When we are guiding someone to tune into their nervous system, safety is paramount. From my own personal experience, it can, truly, be a jungle in there. We need to be sensitive and skilled.

3. Be aware that you are entering sacred space and offer guidance respectfully.

Honouring each and every individual and where they are in relation to their bodies is a high calling – there is an art and skill involved and this needs to be recognised.

In a one-on-one environment, we can help people find tools and practices which regulate their breathing, without needing to over-focus on the actions of breathing. For instance, we know that thinking about experiences of safety and pleasure can reduce the stress response and begin to activate homeostasis.

In a class, however, we cannot identify if there is anyone present who may be triggered by breath awareness practices, and yet we always want to cue connection to breath and our bodies. It is simply enough to have awareness that this might be the case and to find ways to be sensitive to that.

We can offer our presence, language, and attention to invoke a sense of welcoming and allowing, creating a compassionate, kind, and empathic space. In doing so, we can invite both safety and freedom and guide students into their own individuality, instincts, and intuition.

By instructing it in that way, it makes it possible for everyone to have an inclusive experience, giving them an understanding that the option is to explore and be guided by their own body and experience. There is always an option not to do the practice. I have found time and again that this level of invitation in our tone and language can help people relax into a practice to which they might otherwise have had barriers.

If you are offering a specific type of breathwork, offer the option to “stay with your own natural rhythm of breathing if you like. That is a perfectly valid option.”

It also means being aware of our language and tone and that we may be speaking into a place almost entirely inhabited by shame. Can we gently add some light?

4. Establish choice and agency in students’ bodies by offering invitation rather than commands.

This is a fundamental aspect of trauma-sensitive teaching.

As teachers, we have to be careful and sensitive when we guide breathing. It is counter-productive to take on the role of controlling the flow of another person’s breathing. Our aim is to aid our students in taking control of their own breathing. Even the word “control” is barbed. This is why I like the language of befriending rather than the imposing lexicon of “control,” “discipline,” and “mastery” which suggests a slave-master relationship with this intimate and sacred inner pranic field. Try cues like “invite,” “befriend,” “say hello to,” and “become allies with.”

The first step is to guide the student into awareness of how they are breathing in the moment and honouring that. We do not want to shame any inner movement our students are experiencing. Our breathing reflects the feelings we are having – there is nothing to be ashamed of.

When someone is highly anxious, they are usually aware their breathing feels out of control and that can be frightening for them, increasing the threat response and sustaining or escalating the rapid, shallow chest-breathing associated with anxiety and panic. The words “welcome your breathing exactly as it is” in a steady, generous tone of voice can be comforting. We might add, “no matter how it is flowing right now and even if there is resistance to that flow.”

Guided breathing techniques are well-received by many and these can be precious “take-home” practices for a student. There are some excellent and effective breath practices for anxiety and panic attacks, for instance. When we encourage people to explore breath, there is any number of offerings we might like them to experience.

While offering classic pranayama and instructed breath is not wrong (I often suggest a certain rhythm of breathing in my classes and certainly, we need to help students and clients create a wide-ranging repertoire of breath rhythms and practices), using invitational language and open questions is an elegant way of prefacing a breath practice by inviting people into their own body-sovereignty and experience without making them feel they are “under instruction.”

It is important to be aware that specific guided breathing practices are not for everyone. Perhaps it is not for someone on a certain day. If you want people to enjoy their breath, invite them in, make the practice optional. Make it clear that if it is not for them, they can go to any rhythm of breath that they enjoy. Guide them to spend some time in that flow, even if they wander from it. Wandering is okay. Coming back to breath occasionally can regulate breathing and encourage grounding and release of tension.

Here are some cues we might use to connect people to a certain rhythm of breath:

- I invite you to try this rhythm of breath if that feels interesting to you.

- If you would like to, try lengthening and slowing your breath a little. See what happens.

- It can feel really nice to … (instruct breath) … feel free to explore or stay with your natural rhythm of breath if you prefer.

- How does the flow of your breath feel as it moves in your body? What sensations are you feeling?

- Can you feel your breath rising from deep down in your belly or is it further up right now?

- Can you feel your breath reaching into all parts of your body? Don’t worry if you can’t. Simply receive what is happening. Perhaps you can take your awareness into a part that is calling for breath and send soft thoughts to that place. You might feel some breath flow in with the thoughts.

- Are there any delicious or delightful sensations that are accompanying your breathing? Don’t worry if there aren’t. Feel what’s there. Your experience is always valid.

- Everyone has their own personal relationship with breathing. Can you find ways to be kind to your own experience right now?

5. Use personal pronouns.

We don’t have “the breath,” “the heart,” “the pelvis.” I have my heart, while it is in my body I have my breath, and I am pleased to say at the time of writing this (and one successful hip replacement), I still have my own pelvis!

Using personal pronouns allows students to more rapidly enter their own wisdom and experience and encourages self-intimacy rather than dissociation.

6. Recognise how our breath and our emotions are intimately attuned to each other.

Our breathing patterns are powerfully linked to our emotions. For example, there is a specific breath response to threat, which is part of the biology of the stress response and primes us for action.

There are breathing patterns associated with fatigue, depression, and frustration. There are also breathing patterns that come with our emotional experiences of joy, wonder, pleasure, enthusiasm, and thrill.

Our breathing patterns, therefore, speak a language that alerts us to how we are feeling. They also contribute to the way we are feeling.

Tuning into our breathing and its whole mind-body information flow is an intuitive act much of the time. We are naturally regulating our breath according to our needs. For instance, when we are tired and our bodies need more of the fuel of oxygen, we yawn. We sigh out a long exhalation to release tension. We hold our breath when we are under water and one of the reasons for the “drowning response” (where people don’t shout for help when they are in trouble in the water) is conservation of breath for survival purposes. We may speed up our breathing in order to “stock up on breath” before taking action that requires effort. The trance state, in which people retain breath to achieve deeper absorption, is a well-documented tool of meditation and divination. There is no end to the flavours of our breathing and the magic it can weave in our lives, not only for life survival but for life enhancement.

However, there are times when we fall out of love with breathing and feel that the way we are breathing is rendering us out-of-control. When we are under a lot of stress and pressure, for instance, we can get stuck in “emergency” – the adrenalin state which primes us for action, where our rate of breathing increases in order to keep supplying blood flow to our organs. When we are highly anxious, our body assumes a threat is present and can take us into the acute stress response where our breathing becomes associated with panic attacks – shallow, rapid, and causing feelings of discomfort and distress.

When we are deeply sad and depressed, our breath can feel heavy, laboured, or constricted, as if there is a weight on our chest or something wrapped around our throat.

As “the breathers” of our breath, once we have some breath awareness, we can take the instrument of our breath back into our own hands. We can harness our range of breath and choose from it the exact flavour we would like to experience.

In short, we have the power to feel, assess, and change the rhythm of our breathing at any time. We are never without breath. We always have this power.

This is a power that can be learned. This is a power that teachers can teach to enhance the quality of everyone’s mental, physical, and spiritual wellbeing.

7. Avoid clinical language.

When we are anxious, we tend to take rapid, shallow breaths in and out of our chests, instead of from deeper in our diaphragm, into our belly. In clinical terms, this is called “dysregulated breathing.” Be careful with the use of that language, however, when working with students and clients who are doing their best and find it hard to take more regulated breaths.

This “anxious breath” is not a “bad breath” and one should not be shamed for breathing, which, in its simplest and most profound definition, is our current of life-force, there to support us in every circumstance. Indeed, this “anxious breath” has a primal survival function – we need to breathe more rapidly to create the adrenalin and other chemicals we need to face or escape from harm and to keep ourselves safe. We can be grateful for this inner protection.

However, once the danger is over or we are able to believe that we are safe from threat, our bodies are able to assume a regulated breath, which allows for the healthy flow of oxygen to our organs, promoting recovery and feelings of relaxed alertness. This breath uses all the muscles of the diaphragm. Our bellies rise as they fill with breath which travels to all parts of us and they empty as we pour the whole breath out in our exhalation, at a leisurely pace. We may need to practice this way of breathing consciously and regularly, in order to refamiliarize our bodies, especially at times when we are experiencing persistent feelings of stress and anxiety.

In addition to avoiding clinical language, we can be aware of inadvertently body shaming someone, by describing breath rhythms in terms of “good” and “bad.”

I consciously avoid using words like “notice” or “observe,” as our aim is to provide a safe passage into embodied self-engagement and such words can invoke a sense of being detached from our own breath and bodies, which is dissociative. Instead, I like to use the language of feeling and sensing. Our breath has a texture and a temperature, and it is a flow we can engage with somatically, rather than needing to stand back, watch, and bear clinical witness. Learning to feel the way our breath is tending to us as a gentle, soothing flow can bring us more deeply into states of comfort.

We are opening space for a biological shift to happen.

When we pay attention to our breath without adding further stress to it, we are already engaging in the first stage of breath regulation. The tone of voice of our ally can help to regulate the tone of panic in our inner voice until we are able to take over and receive the voice of an ally as our own.

Connecting breathing to positive emotional states such as safety, ease, love, and pleasure can be an effective way of facilitating natural breath regulation without having to make any such judgements.

9. Connect breathing to positive emotional states.

We know from the fields of psychology and neuroscience that connecting to positive emotional thoughts, memories, and feelings activates the relaxation response and releases “feel good” hormones into our nervous system.

Music that we like also has this function, as does mental and sensory pleasure.

Our breath patterns alter accordingly. A powerful practice for mental wellbeing, therefore, is to connect breathing to emotional states. There are numerous ways we can do this.

We can invite people to breathe with:

- A cherished memory

- A pleasant feeling

- A pleasant fantasy or visualisation

- A sensory experience (e.g. smelling or tasting something delicious)

- A way of breathing which might feel really pleasurable in their own being right now

- The question, “When you have thoughts and feelings of ease, (or pleasure, or any other positive emotion) how does your breath move/feel in your body?”

10. Using props can help.

We can also offer props to help people breathe more easily and feel safe. A blanket across the sacrum can be very grounding and also a visual aid to breath awareness and to assist deep abdominal breathing.

We can invite students to use props that open up the aperture of their breathing and suggest chest-opening restorative poses or simply cue them to become more physically comfortable.

With children, we might explore using props like balloons and bubble-blowers.

We can cue relaxation in the body and offer techniques such as progressive relaxation. Breathing automatically begins to settle once we release tension from our muscles as we are reversing functions that are part of the stress response.

11. Guide energetically.

A teacher needs to be conscious of their own breathing pattern and ensure it is well-regulated. Known as “co-regulation,” this helps us to centre and transmit energetic vibrations that are steady, grounded, relaxed, and secure.

Be aware that everyone breathes at different habitual speeds and although it is not wrong to try and guide a class, for instance, into one harmonious breathing rhythm, it is neither necessary nor necessarily better than, giving breath cues that allow people to find their own natural and available pace and timing.

For instance, I may give the invitation, “I am going to count out the three-part breath. If you would like to join me, go ahead. If you find counting doesn’t suit you, feel free to drop it,” and then I add, “Of course.”

The tone of our voice, the words and phrasing we use, and our presence as centred in our own natural being energetically offers a range of permissions that allows our students to engage with their own inner currents of wise guidance.

There are so many ways we can be an ally and a facilitator that are not imposing but awakening and liberating for our students. A vast number of these are energetic.

12. Invite people to enjoy range and exploration.

Many people don’t think about the possibility of how pleasurable breath can be. It is simply something automatic to them, that either does its job well or not. People who struggle with anxiety might find breath to be more of a “problem to be solved,” rather than something to take pleasure in.

Those of us who delight in experiencing and teaching meditation have entered doorways into the full magic of breathing. We know how multi-faceted it is. One of its profound qualities is that it can connect us to our psyche and emotions in ways that strengthen, enliven, and heal us and can contribute massively to our mental wellness. It is thrilling to share what we know.

Meditation teachers should have a range of breath practices they like and teach this range across their classes and workshops. For every breath exercise we teach, there may be a profound impact on even one person who can then take that practice into their life and see potent changes arise as a result. So much so, that they may be inspired to share it with others in their lives and that makes it worthwhile.

The broader the range of breath practices we teach and the more numerous the ways we frame that teaching, the more we can help as many people as possible find freedom, joy, and healing as they harness the transforming power of their breath.

References and Resources

Mental health reference – Penman, Stephen J (2008) “yoga in Australia: Result of a National Survey”

Facebook Pages for Support for Meditation Difficulties Research:

- Cheetah House

- Research on meditation-related difficulties group

- Meditation-related difficulties support group

Roche, Lorin (2001) “Breathtaking”, Rodale Books

Nestor, James, (2020) “Breath, The New Science of A Lost Art”, Riverhead Books

Treleaven, David (2018) “Trauma Sensitive Mindfulness”, WW Norton & Company

I have a variety of guided breath meditations and explorations on Soundcloud in this playlist.

Illustrations by Ksenia Sapunkova

Edited by Jordan Reed

Enjoyed reading this article? Consider supporting us on Patreon or making a one-time donation. As little as $2 will allow us to publish many more amazing articles about yoga and mindfulness.