Read Your Brain on Yoga. Part I: Motor Control here

Sense of Self

One thing that we share with every other form of life is a need to intake sensory information. Every living creature has a nervous system; a working network of structures and fibers that can intake sensory information, process it and then interpret that information into action. It is our body’s holistic system of communication both internally and externally!

Nervous systems can range from the most rudimental amoebas, who can react with their environment to find food and reproduce; to the most complicated octopi who can problem solve and camouflage. Size doesn’t matter when it comes to interpretation either; the brains of the smallest wasps and the largest sperm whales may act differently, but they all serve the same purpose of relaying and processing information before creating action.

While we may not have the biggest or most complicated brains, human beings are quite interesting in that we have a very high functioning brain. We have over 100 billion neurons (more stars than the Milky Way) and other supporting and protective nerve cells called Glial cells. All these neurons work together to help us process information from our environment; smell, taste, sight, touch, and hearing. At any given time, our sensory organs are intaking this information, relaying it back to our brain, then processing it into action.

For many creatures, sensory information from the environment leads to a response that helps create physical movement. Humans are no different. Much of the sensory information we intake results in physical action too; we do often have an extra ability though: we can observe our thoughts and think about our actions.

In order to walk, your brain has to intake information from a multitude of different places. For example:

- Your eyes determine the horizon line and help your brain measure the depth of terrain so you can adjust your steps to slopes and uneven surfaces.

- The otoliths in your ears and proprioceptors in your neck relay to your brain the position of your head so that you can spatially orient your body and adjust it as needed along your path.

- The skin and mechanoreceptor cells of your feet tell your brain the amount of pressure each of your steps makes and adjust so that you can redistribute your center of gravity accordingly.

- Every joint, along with your connective tissue, gives information about their positions and orientations via specialized nerve cells. This information then allows your brain to tighten/loosen and concentrically, eccentrically, and isometrically contract your muscles to result in movement.

- You can also take all of the above and think about walking before/during/after you do it!

All that information comes together and integrates with your nervous system within fractions of a second to help you move. Most of the time, it’s subconscious too!

From this information, you can see that in order to really understand the nervous system, our first step is to explore one of it’s most pivotal purposes: how we intake information and how this information is then interpreted into the body.

Technical Terms:

Afferent: Sensory information taken from a nerve cell to the spinal cord and then the brain.

Efferent: Information taken from the brain to the spinal cord and a motor neuron in a muscle to execute an action.

***Most peripheral nerves are composed of 80% afferent/sensory fibers and 20% efferent/motor fibers!

The first article of this Neuroscience series on Motor Learning talked a lot about how we intake and process information from hearing and sight. Specifically, we looked at how demonstrating a posture can help almost anyone copy the position in their own body and how the words we use can be an effective medium for communicating nuances and awareness. I also briefly touched on the skin and how physical touch can be a powerful tool in the process of motor learning.

This article is all about our sensory system, its origins and development, and the biggest sensory organ: the skin. We will explore how specialized nerve cells embedded in the skin and connective tissue beneath the skin can give us a sense of what our body is doing in space as well as other information like temperature, touch, vibration, etc.

One of these afferent senses, proprioception, is especially important because it is used by our nervous system to determine the next movement that we will make.

Proprioception: perception and awareness of the position and movement of the body.

***Note: In the yoga world, some people confuse proprioception with a different sense: Interoception. Interoception refers to a sense of what’s going on inside of the body. This is an objective feeling and is often felt when we feel hungry, hot, cold, or thirsty.

It’s a little confusing, so you can think of this sense as your sense of the physiologic state of your body vs proprioception, which refers to the physical position and movement of your body.

Before we get into the depths of proprioception, how it can go awry, and how we can utilize and empower it in our yoga practices and classrooms; I think it is important that we start at the beginning and discuss the origins of proprioception, as well as look a little into our other afferent senses and how they play into our yoga practices.

Article Index:

- Development of the Nervous System

- Organization of the Nervous System

- Environment “Perception and Threat”

- Touch and Yoga Assists

- Proprioceptive Awareness and Exercise

My hope is that the story of the development of your nervous system will demonstrate just how connected our body and its parts are, in addition to the important role our skin plays in how we move. The nervous system is, after all, the great connector of the trillions of cells that embody you! 😉

Development of the Nervous System

Warning: Technical Info Lies Ahead

The next segment will detail some of the embryology and development of our skin and nervous system. You can skip ahead to the more practical portion and come back to this segment later to understand some of the anatomic basis if you like.

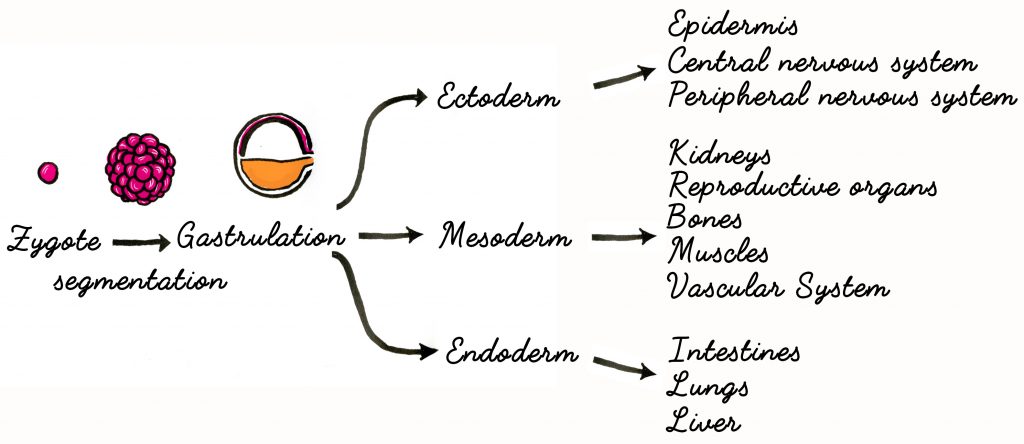

Before we were trillions of cells, we were a mere bundle of them. As this bundle of cells, we had three main tissues that would differentiate into who we are today.

Mesoderm: gives rise to bones, muscles, fascia, the heart and circulatory system, and internal sex organs.

Endoderm: turns into the inner linings of many systems such as the gut & GI tract, liver, pancreas, and structures in the lungs, ears, and urinary system.

Ectoderm: develops into parts of the skin, the brain, and the nervous system. It also includes your spine, tooth enamel, mouth, anus, nostrils, sweat glands, hair, and nails.

The mesoderm and its muscles, connective tissue, and cardiac system are cool, and the endoderm does a good job lining our tubes and forming our gut, but the emphasis of this article is on the ectoderm and how it connects us to our body and environment.

The ectoderm derives from the outer layer of cells when we are an embryo. Some of these cells eventually fold to become a neural tube which will later become our spinal cord and brain and a neural crest that becomes a part of our skull and peripheral nervous system. There is also a surface ectoderm that becomes the epidermis (top layer of our skin).

These origins are pretty interesting, and understanding them can give you a better sense of how connected our body is. Our body is not the fragmented parts we learn in traditional anatomic models; everything flows together and is interwoven in complex and fascinating ways. We’re much more like a seed growing into a tree rather than a Lego man who was put together in different parts.

Through understanding the origins of the Nervous System, you can also get an idea of how the Nervous System and the skin are connected. Since they derive from the same embryonic tissue, they very much influence each other. This will become especially clear in the next segment when I talk about specialized nerve cells in the skin and how they relay information to the brain. It’s also useful to know because when I discuss props and yoga assists later, you’ll know that by influencing the skin, you’re very much influencing and communicating directly to the nervous system!

Organization of Your Nervous System

Warning: SUPER Technical Information

We’re going deep into Neuroscience in this next segment. This stuff also isn’t completely necessary to understand the practical portion, but it is a nice background to the information I’ll supply later. Body nerds keep reading ahead, otherwise, be prepared to fall asleep. 🙂

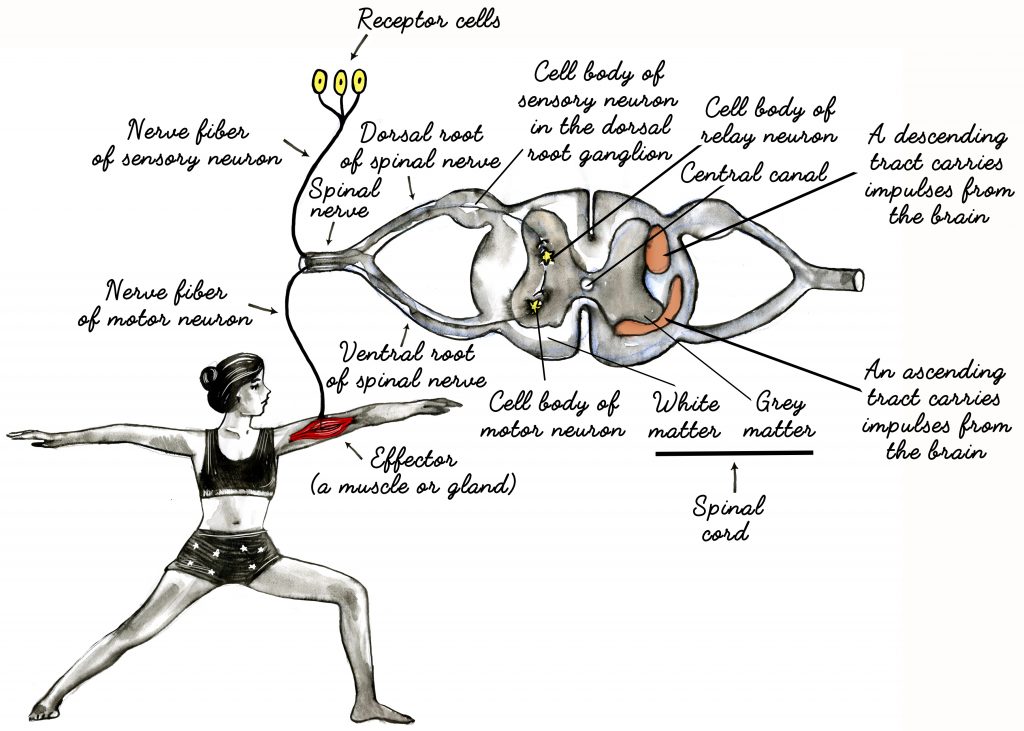

Now that we understand the connection between our skin and Nervous System, I’ll elaborate on the Central Nervous System and Peripheral Nervous System.

Central Nervous System (CNS) – Brain and spinal cord.

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) – Nerves that exit the spinal cord and travel to every area of the body.

Sensory Receptors: Specialized nerve cells that gather information (like heat, vibration, pressure proprioception, etc.).

Motor Neurons: Specialized nerve cells in muscles and glands that carry out the signals and actions.

The role of the Peripheral Nervous System is to take sensory information gathered by sensory receptors from the organs and limbs and relay that as fast as possible to the spinal cord and brain. It also includes motor neurons, which then carry out the actions relayed back by the Central Nervous System.

Recall from before that sensory nerves are afferent and send information to the CNS and motor neurons are efferent because they carry out actions from the CNS.

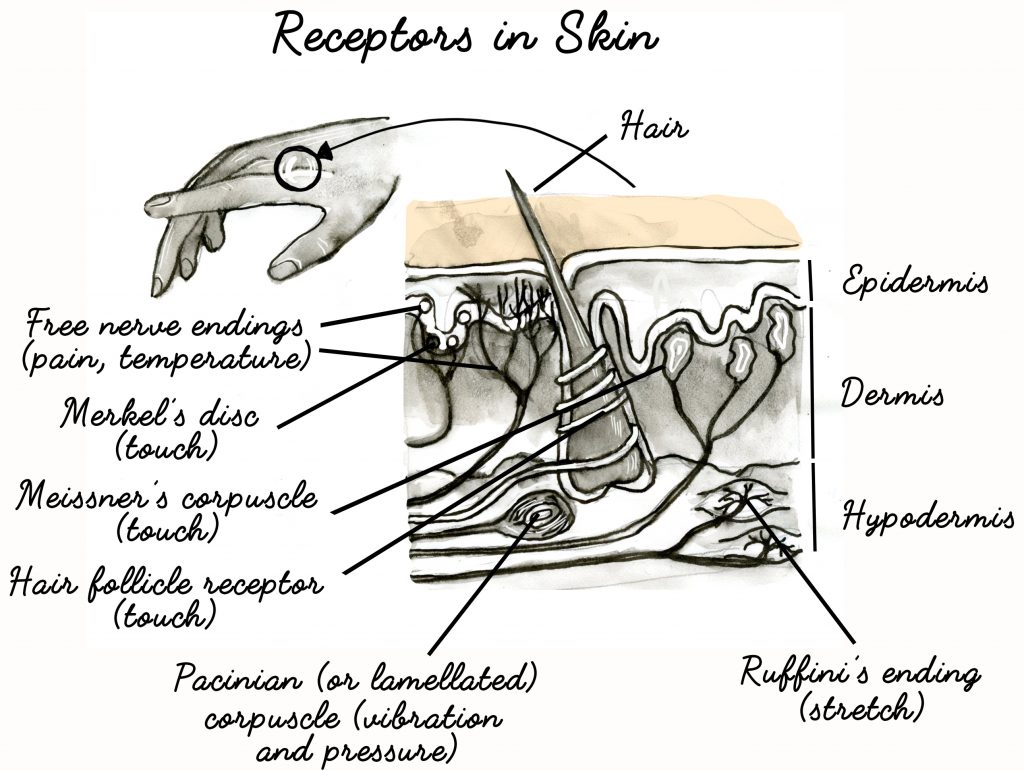

We know from the origins section that our Epidermis (the top layer of skin) derives from the same tissue as the brain. The other layers, like the Dermis and Hypodermis, come from the Mesoderm (same as muscles, bones, and connective tissue). While not of the same embryonic tissue, they are still embedded with a bunch of specialized nerve cells to help us relay information about our current condition and environment.

Mechanical and Sensory Receptor Cells in the Skin:

- Merkel’s Corpuscle – Slow adapting touch, degree of pressure exerted on skin (like holding a pen), two-point discrimination, spatial info like edges and shapes

- Ruffini’s Ending – Stretch

- Meissner’s Corpuscle – Light Touch, very abundant in lips, fingertips, palms, feet, nipples & genitalia

- Pacinian Corpuscle – Vibration & deep pressure

- Hair follicle Receptor – Information about hair being moved

- Free Nerve Endings – Pain & temperature

Just about all of these cells are used when we take a yoga class. They send a wealth of information to our brains: like the squishiness of our mat under our feet, the pressure of the blocks against our skin, stretching regions of our body, or the feeling of touch from our instructor as they help coach us through a posture.

The cells above describe the different information that the sensory and mechanical receptors in the skin relay to the brain. These are tactile signals and are important to understand because it’s how our Nervous System intakes information from the skin about what we touch. I’ll show you in a moment how this information reaches the brain via spinal tracts of neurons, but let’s first take a quick detour to discuss one more bit of crucial sensory information.

Proprioception

Another separate component to all of this is proprioception. This is really important to understand as a yogi or yoga teacher because it’s related to your balance and how you move your body. Proprioception is how your brain gets a sense of your body’s position in your environment.

Proprioception is the sense of the relative position of one’s own parts of the body and strength of effort being employed in movement. It can also relay information about the speed in which your body moves too! An easy way to remember the relationship between proprioception and our body is through the ABC’s of Proprioception:

A-Agility

B-Balance

C-Coordination

Proprioception comes from specialized nerve cells in muscles (muscle spindles), tendons (golgi tendon organs), fascia, and joint capsules. Your body is littered with proprioceptors, many of which are in your neck* and every single joint!

*You have a lot of proprioceptors in your neck because your brain wants to know the position of your head at all times. The positioning of your head will directly influence the way your body moves.

**This is why it’s difficult to move your head in balance poses like Ardha Chandrasana (Half Moon)

Proprioception syncs with the eyes and vestibular system of your body to help create a global picture of what your body is doing in your environment. Your Vestibular System encompasses your inner ear and is responsible for your balance. Your inner ear has the ability to detect movement and orientation.* This combines with the stretch receptors in the muscles and the proprioceptive cells in the joints and ligaments, plus your eyes, to give your brain a picture of what your body is doing.

*It’s why you don’t fall down when you close your eyes!

One term commonly affiliated with proprioception is kinesthesia. Kinesthesia refers to movement sense and can be defined by the brain’s interpretation of proprioceptive information.

There are two types of proprioception:

Unconscious: primary function is to monitor and modify movements. It is involved in the acquisition and maintenance of complex, skilled movements such as walking, talking, and writing

Conscious: deals with aspects such as judging the weight of an object or where a person’s limbs are in space.

Conscious proprioception can be described as being mindful of the movement you are making. Your ability to sense and judge the speed and movement of your limbs when you practice is conscious proprioception. Your Unconscious Proprioception is your backup and helps to fine-tune your movement along with coordinating complex things such as walking.

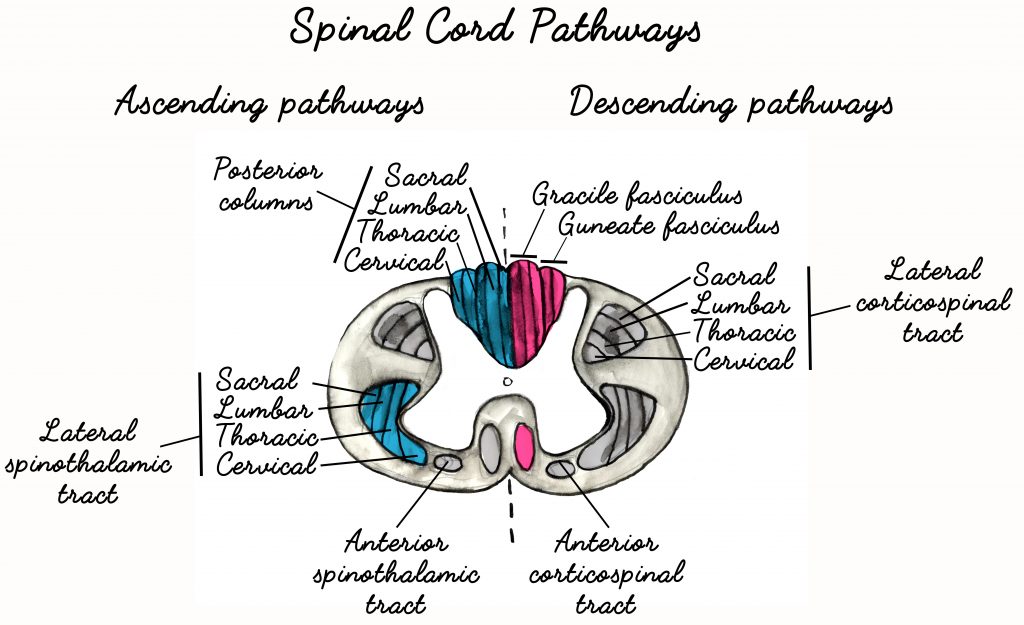

Spinal Cord Pathways

Okay, now that we know how the Peripheral Nervous System works via the sensory information we get from our environment (via the skin, mechanoreceptors, eyes, ears, etc) and the motor neurons that move our muscles to carry out the actions of our brain, we can take a quick look at how the Central Nervous System is organized to relay all this information.

In the Motor Learning article I talked about how the brain is organized. I’ll spare you those details because we’ve already surpassed information overdrive and we haven’t even gotten to the practical portion. Stay awake! We’re almost there 😉 (Maybe look at that section again after this to get a nice review and holistic picture of the nervous system’s organization)

The spinal cord is organized to help relay all the information that was described before. It is quite fascinating how all of this works and is designed to get information translated as quickly as possible for immediate action.

Ascending Pathways:

- Lateral Spinothalamic: Pain and temperature

- Ventral Spinothalamic: Pressure and crude touch

- Dorsal Column: Vibration, proprioception, two-point discrimination

- Spinocerebellar: Proprioception in joints and muscles

- Cuneocerebellar: Proprioception in joints and muscles

- Spinotectal: Tactile, painful, and thermal stimuli

- Spinoreticular: Integration of stimuli from joints and muscles to the reticular formation

- Spino-olivary: Accessory pathway to the cerebellum

Descending Pathways:

- Corticospinal: Carries out voluntary, discrete, and skilled motor activities

- Reticulospinal: Regulates voluntary movements and reflexes

- Rubrospinal: Promotes flexor and extensor muscle activity

- Vestibulospinal: Inhibits flexor and extensor muscle activity

- Tectospinal: Postural movements from visual stimuli

Note that there are a lot more sensory tracts than there are motor tracts. This helps give us a big overview of how everything is segmented but ultimately integrated into the nervous system. This integration is the foundation for the next few segments. With all this new Nervous System knowledge you have, it’s time to make things practical and look at how it plays out in our yoga classrooms, practices, and teaching!

Pain: Perception and Environment

Welcome to the practical portion of this article! In case you skipped ahead, the last few segments were mainly to detail the neuroanatomy of how your nervous system takes in tactile information from the skin and proprioceptive information from your connective tissue. I also detailed how our Nervous System is organized to take in information and process it into actions.

Let’s first talk a little bit about how things can go awry for your sensory system. This will give us a good basis to discuss the calming environment of our yoga studios and rooms, plus inform how prop usage and assists can encourage the highest level of performance for our nervous system.

Part of being human is feeling and responding to pain. An experience of and response to pain is one of the things I believe we all share. For those that study pain and have been in pain, we know it can get really complicated!

I won’t go into too much detail on pain science, that’s a whole different beast of an article. For those interested in pain science, I would highly recommend looking up the Bio-Psycho-Social Model and some of Greg Lehman’s work. Also the book Explain Pain by Lorimer Moseley & David Butler is fantastic.

Pain is a sensation that is a part of your Nervous System! It plays into our survival mechanisms and is one way our nervous system can communicate that there is a threat or throw up an alarm that we shouldn’t go further into whatever is signaling the pain and hurting us.

Sympathetic Nervous System: Flight, fight, or freeze and the stress response

Parasympathetic Nervous System: Rest and digest; slows the heart and relaxes muscles

Pain signals us into a Sympathetic Nervous System response. Pain is a threat and therefore triggers our survival mechanisms. As Dr. Perry Nickelston says: Pain is a signal for change. It is an alarm that something is wrong. Before we go on; one of the most important fundamentals I hope you take away from this article is:

Always practice pain-free range of motion.

The old school “no pain – no gain” logic is gone. It’s foolish! If you feel pain, MODIFY, or SKIP. You only make matters worse by pushing through pain.

****If you practice with teachers that tell you to “push through pain,” “settle into pain,” or “find comfort in a painfully uncomfortable situation,” they are poorly informed. They are not respecting your nervous system and the alarms it is sending you! In my opinion, this is seriously the worst thing you can EVER encourage. Relatively comfortable and pain-free = a safe and sustainable practice.

For those that do exercise or move with pain the best advice is monitor it and cease the activity if your pain increases. For example: If I am planning on doing squats and my back hurts on a pain scale of 3/10 I can continue to do squats so long as my pain stays there or diminishes. If my pain increases to 5/10, I therefore stop squatting, and it goes back down; I can perhaps continue to do my squats but modified so I do not increase my pain again. If I’m squatting and my pain jumps to 5/10 and stays 5/10 even after I’ve stopped and rested, then I am done with that exercise.

Summary: You can work out with pain, it’s likely good for you. But if you pain increases, and stays increased then listen to your body and give it more time to rest/recover.

Pain-free range of motion (ROM) is important because it is one way we can trigger and stay in a parasympathetic dominant state. For those of us who do experience pain, pain-free ROM is an essential step in recovery because it teaches your nervous system that you and your environment are safe. Safe-feeling movement helps decrease overall muscle tone from some of the physical guarding (neurologic tension) associated with pain.

If you are a yoga teacher, this is important to understand because it is very likely someone in your class came to yoga because they are in pain. Many modern yogis started yoga or became more serious about it because it helped them recover from an injury. It is important we respect this, provide options, and encourage pain-free movement! Yoga shouldn’t hurt; it should help.

Pain can also alter the very position of your body and how well it senses too. People with chronic pain, pain that they have had for a long time, are likely to be compromised in their proprioception. It is also possible their brain’s lack an ability to feel and move specific regions too.

Neurogenic Inflammation: Irritation and inflammation of peripheral nerves.

This can come from constrictions in the skin, muscles, and related fascia. It can be related to hydration, but also neurologic tension (where the nervous system reflexively constricts muscles and eventually joints because it feels pain/threatened and wants to protect and guard your body from further injury)

Cortical Smudging: Loss of an ability to feel and also perceive movement of an area due to chronic pain

With chronic pain, your brain can undergo neuroplasticity that will desensitize it to a region that feels pain. This area becomes “smudged” or loses specificity in the motor and sensory cortex of your brain.

Ex: With chronic knee pain, you may lose your ability to two-point discriminate or feel distinct areas of your knee. You may also have a hard time coordinating movement and balancing.

Both neurogenic inflammation and cortical smudging can impair your nervous system’s ability to take in information. In these scenarios, proprioception is one of the first senses to diminish because the feeling of pain can overcome the feeling of where your body is in space. This is especially evident in cases of chronic pain.

Using this information, though, we can assume that a few people (maybe even ourselves) are impacted by these afflictions. You can use this sensory intake & integration information to better the way we warm up our bodies and use props in our classrooms. We need to stimulate nerves in the body (mechanically through the skin or through decompressing neurologic tension). This will help boost proprioception and also improve the cortical map our brain has of our body!

Stimulating the Nervous System

Cultivating awareness mechanically

I like to call this technique, “Creating a frame of reference.” Far too often, Yoga Teachers will teach anatomical terminology or use the names of specific muscles/bones/areas in their classes. This is all assuming that average people know what that region is. Even if they know what that region is, the teacher is also assuming that region is well defined in the sensory and motor cortices of the students’ brains!

You can fix all this with a fairly simple solution: TOUCH. Physically touch the anatomical area that you are focusing on. You can also rub it, pat it, tap it, swirl it, etc. Mechanically stimulate the area for 10-20 seconds and get all those specialized nerve cells in the skin to send signals to the brain! This super quick technique will improve that area’s representation in your cortices, and you can connect to it much more effectively.

Yoga teachers: You can instruct your students to touch themselves. A lot of light has been given recently on abuse and touch and also more trauma informed practices, so often it is within our best interest to have our students use their own hands on their own bodies. They can benefit from the tactile stimulation in their fingers in addition to the area that you have them touch and bring awareness to.

Here are some simple examples:

The Sternum and Backbends

Scapular Awareness

Helping Tissue Glide

Hydration and neurologic tightness will affect how our muscles and tissues glide on each other. This sliding movement is essential because the nerve cells will detect the movement and relay it to the brain (stretch and proprioception). It is also nice because, now that there is more space, there is less constriction imposed on the peripheral nerves.

Thoracolumbar Fascia Sliding w/ Block

Pin and Stretch

Dermal Traction with Movement

Breathing in yoga alone helps calm and relax our nervous system. The brief overview of pain science and techniques above are here to help teachers become more efficient in connecting people to their bodies and help students better connect with themselves! This makes for a great warm-up; once people are connected to their body, they are more likely to move safely, pain-free, and sustainably in their practice!

Remember: Yoga does a fantastic job of helping people. Let’s make sure we honor that and shy away from things that signal pain and may hurt folks!

Touch and Yoga Assists

Now, let’s integrate all of this cool nervous system information into how some of us yoga teachers practice Yoga assists. For my non-teacher readers, this information may help you observe whether or not your teachers are respecting your anatomy. Plus, you’ll gain some cool scientific wisdom about physical touch!

I’d like to start addressing the controversy of Yoga assists and also share my personal opinion on them:

- I use yoga assists almost every time I teach. I believe it is VERY important to ask for consent, especially if you are going to work individually with someone. (If you’re going to help someone after class, ask again, even if you did the blanket, “Raise your hand if you don’t want to be assisted today” statement at the beginning of your group class),

- I AM NOT a fan of “deepening assists”* or assists where a teacher pushes their student further into a posture. I believe that these serve no purpose other than “it feels good in the moment” and are very dangerous. You can easily push someone too far and compromise their joints.

- If you practice these, go for it. In my opinion, the only person you’re helping with these assists is your ego and that student’s doctor’s wallet from all the physiotherapy bills you’re racking up pushing them past the active ranges (or worse, passive ranges) of their joints.

*I talk more about deepening assists in the next article in this series on Range of Motion. To read more, you can also check out Katy’s article, Why Traditional Adjustments Should Be a Thing of the Past.

Okay, disclaimers about foolishness and personal biases out of the way, now I’d like to teach you how I assist using minimal touch to get people to perform their best in yoga asana.

Minimal “Light Touch”

If you read the above segment about all the different nerve receptors in the skin, then you know that we have specialized nerve cells that detect light tough, deep touch, pressure, and vibration. Light touch is what we can really emphasize because these are going to relay right up the spine to the brain and help improve the awareness and sensation there.

The use of touch in teaching is really simple: you touch whatever you’re verbally cueing!

Ex: Backbends: “Elevate your chest as if someone’s hand was behind your shoulders” [put your hand behind someone’s shoulders].

Warrior II: “Draw your shoulders down your back” [Touch the bottom of the scapulas and maybe lightly glide your hand down the middle spine].

Yeah, it’s that simple. And there’s no risk of injuring someone here. You’re helping them help themselves connect to the action! I encourage you to make up your own; almost every cue should have a light touch assist that can go with it. Many also communicate the “lines of energy” or actions of the posture.

I’ll note I also assist via blocking/providing barriers for movement or providing targets for people to guide their body around (external cueing via physical assisting for those that read my motor learning article). These are a little more advanced, but also just as minimal. I’ll save those for another article. 😉

Boosting Proprioception – Exercises

In this final portion if this article, I want to detail a few different methods in which you can work with the proprioceptive system of the body. This can be beneficial because it is a cool way to accent your practice and potentially better your balance and body awareness.

Closing Your Eyes

Quite simply, closing your eyes takes out one major component of your brain’s ability to feel the orientation of your body in its environment. You can try it with one eye and both eyes.

Here’s an easy progression:

- Stand in Samastitihi, close your eyes, and rock around (forwards – backwards, side – side, circles, etc).

- Step one foot slightly forward, lift your heel and keep your toes down. Close your eyes, then switch feet.

- Try and lift your leg all the way into a 1 legged mountain pose, then close your eyes.

- Close your eyes first, then lift your leg into 1 legged mountain!

Have fun with that, please don’t fall, and hold each layer as long as you see fit. Hold time is a great way to make any layer harder and also track your progress!

Unstable Surface

Put your hands or feet on blocks, and do your normal poses! Unless it’s a cork block, your yoga block has some squishiness to it. That unstable surface requires the proprioceptors in your hands/feet to fire constantly so that your nervous system can adapt to each instantaneous movement.

***You can always try folding up your mat and balancing on it too!

Once again, please don’t fall and have fun!

Conclusion

Oh wow, what a journey, right?! The sensory system is a huge part of our nervous system, and now you have a decent idea of where it came from, how it’s organized, and how it works! There are not many yogis who understand the intricacies of this system. Trust me, knowing this and utilizing the things you learned here can really make a huge difference in the way you practice and teach yoga.

Central Themes

- Create a safe environment! Pain-free movement is the best kind of movement.

- Assume people come to class with pain and use easy movements to improve the way their body moves and the awareness they have of their body.

- Props and touch can be very helpful in cultivating awareness.

- Proprioception is a great sense to train because it affects our agility, balance, and coordination!

I know it was a lot of information, and I hope you enjoyed it. Remember: you can always come back and read it again, especially if you just read the practical portion. I’d also recommend you reread the motor learning article (first part of the series) and see how this information compliments it!

Next up in this series is Range of Motion and it’s going to be amazing 😊

-Dr. YG

Works Cited & Additional Resources:

1. Peripheral Nervous System – Development and Stem Cells

2. Functional Neuroanatomy of Proprioception

3. Proprioception, ScienceDirect

5. Ascending Tracts of the Spinal Cord

Read Your Brain on Yoga. Part I: Motor Control here

Read Your Brain on Yoga. Part III: Range of Motion here

Illustrations by Ksenia Sapunkova

Edited by Sarah Dittmore