It’s finally time to focus on the physical! The last two parts to this series were heavy hitters in neuroscience and were largely emphasized how we learn, orient, and interact with our environment. If you haven’t already, you can read them here:

Part I: Motor Control looks into how we learn to move and techniques we can employ to be effective and efficient at moving on and off our yoga mats

Part II: Proprioception discusses how we sense our body in space and techniques we can use to improve our proprioception.

Part III is all about the physical side to the nervous system, read: Range of Motion.

Article Index:

- Range of Motion – What is it, and how is it governed by our nervous system?

- Range of Motion – Injuries

- Mobility vs. Flexibility

- Practicum

Finally, we get into the really, really good stuff 😉

Understanding Range of Motion

Let’s start by defining some useful terms every yoga teacher SHOULD know:

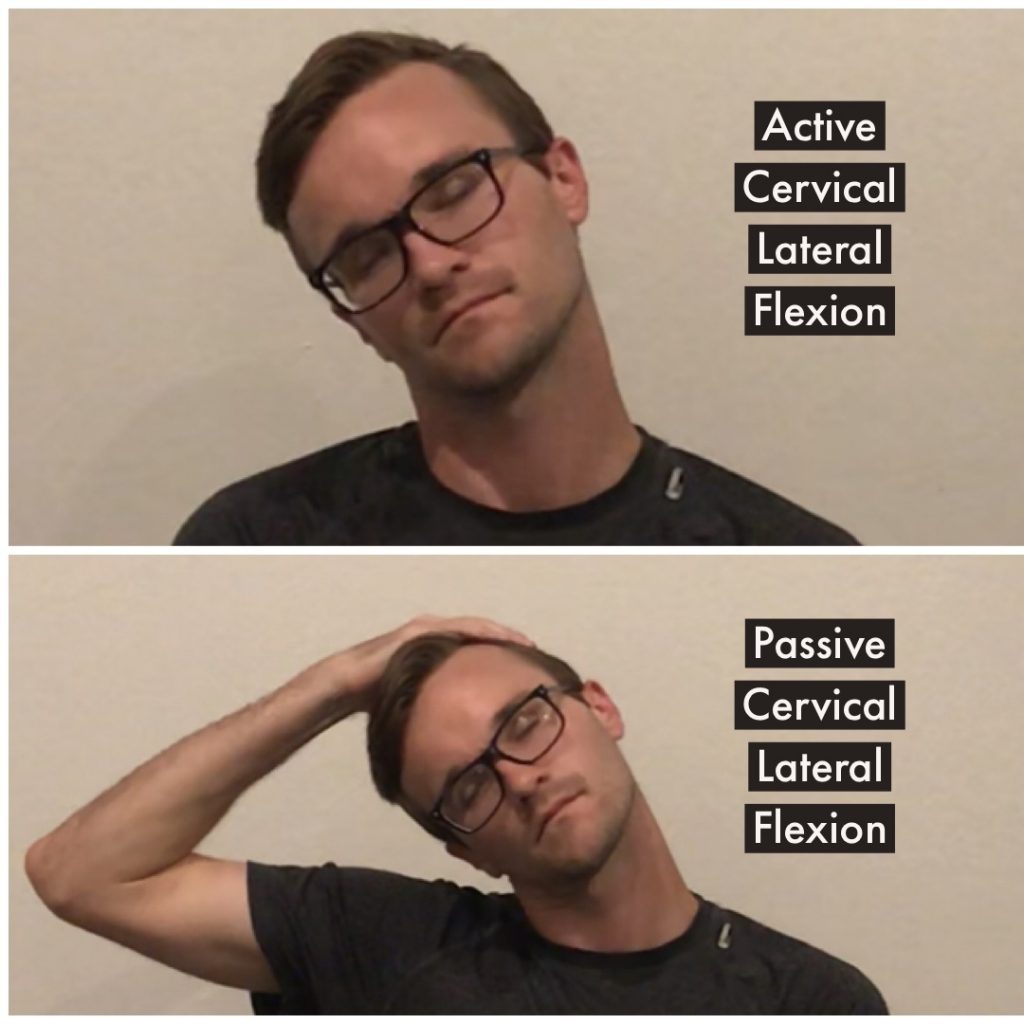

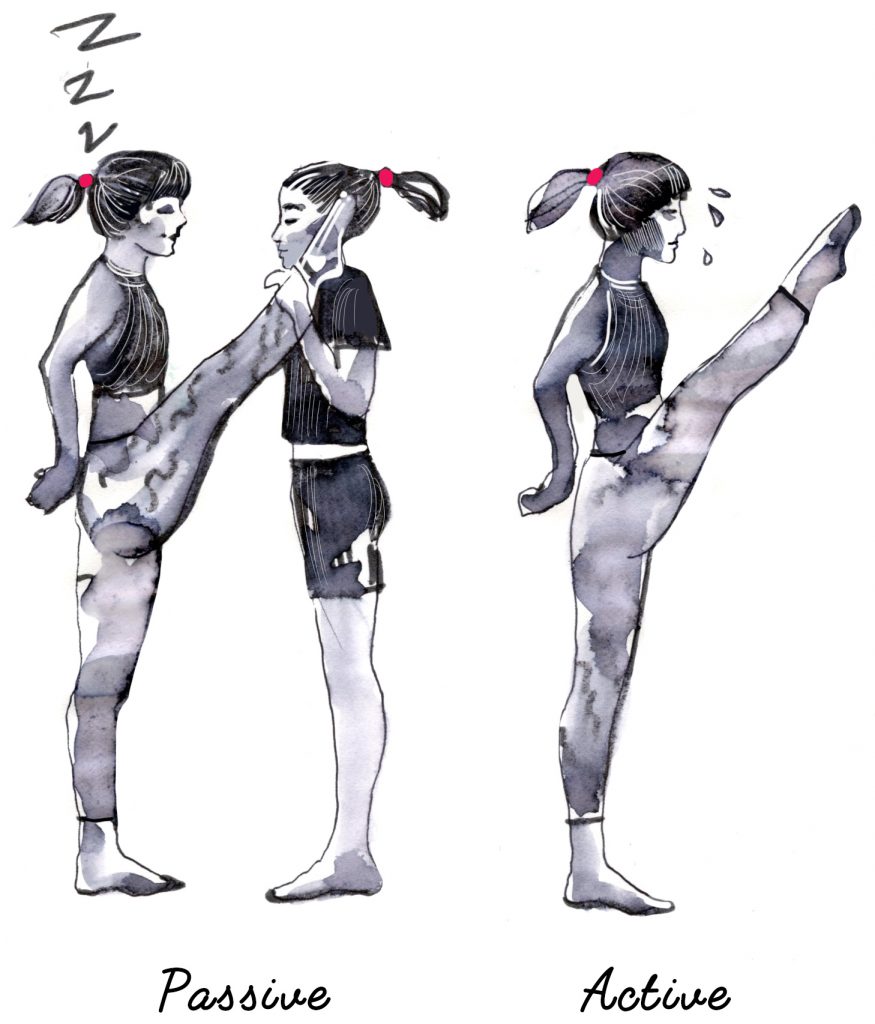

Active Range of Motion (AROM): How you move your body without any external aid

Passive Range of Motion (PROM): When an external force helps move your body

Our Active and Passive Range of Motion are often very different from each other. Here’s a quick example:

Lateral Neck Stretch:

- Active: Bring your ear towards your shoulder, try to keep your shoulder still

- Passive: Bring your opposite hand to your top ear and see if you can stretch your neck further by using your hand

You will always have more Passive Range of Motion compared to Active. By using the overpressure of your hand, you exerted an external force and were likely able to stretch your neck a little bit further.

Why?

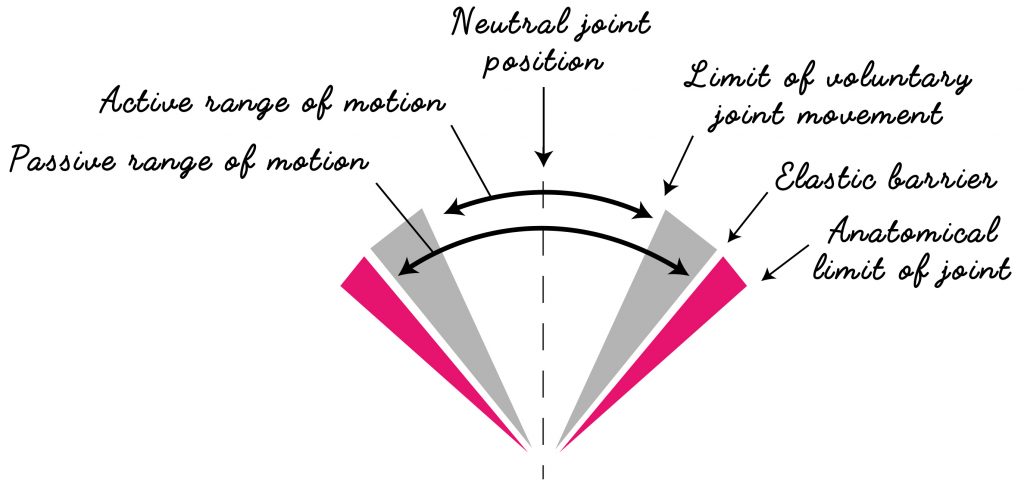

Each and every joint in our body has degrees of freedom (or range of motion). There are barriers built-in physically and by your nervous system to help them function optimally and safely.

Here are the three main barriers:

- Anatomical Limit – This is the very end of the range of motion and represents a physical barrier. You physically can not go further and if you do you risk breaking, fracturing, or soft tissue injuries.

- Elastic Barrier – The elastic barrier is also physical; it exists at the end of Passive Range of Motion. It’s the resistance that you felt at the end when you used your hand to stretch your neck. A little space exists between the Elastic Barrier and Anatomical Limit; it’s called the Paraphysiologic space and is only really used by manual therapists during joint manipulations and mobilizations.

- Limit of Voluntary (Active) Movement – This barrier is entirely neurologic. It means you moved the joint actively without external assistance and your nervous system stopped you at this limit. From neutral to the limit of active movement is your Physiologic joint space.

As yoga teachers and students, you don’t need to concern yourself with the Paraphysiologic space. That’s for manual therapists like Chiropractors and PTs when they properly assess and treat patients because joint manipulations and mobilizations can be effective modalities in pain reduction and improving biomechanics.

Research:

- Overview: Spinal Manipulation – Lower Back Pain

- Systematic Review: Manipulative Therapy for Shoulder Pain

Yogis *NEED* to understand AROM, the Active Limit, PROM, and the Elastic Barrier. It is essential information because it’s exactly what we’re influencing in yoga asana!

Why do we have an active limit? Why does our nervous system stop us at first, but allows us to go further (or “deeper”) if we receive some external pressure?

The answer is that your nervous system is restricting your ROM in order to protect and keep you safe. AROM represents the movement that you have control over. PROM represents the space you can still move in, but only with added help because you *DO NOT* own that movement.

For example: In America, our cars have a governor, or speed limiters, installed by the manufacturers. Its purpose is to limit the car’s engine so it can only reach a certain speed. It basically ensures that you uphold the speed limit and cannot outrun the police.

Your nervous system is like a car’s governor, but instead of speed, it limits range of motion. And instead of making it easy for the police to catch you, it’s doing it for the sole reason of protecting you!

What do most of us typically do in yoga instead of listening to our body and this neurologic barrier?

We stretch further and further, extending ourselves into our Passive ROM (The space your muscles don’t have efficient control over, in case you forgot).

Injuries with Range of Motion

Range of Motion is one of the most important neurologic and biomechanical principles a yoga teacher, and practitioner, can understand (hopefully I’ve repeated that enough to get you to pay close attention). Every yoga pose deals with some degree of ROM and every instruction, cue, and assist is likely influencing it in some way!

The difference between active and passive range of motion alone can change our physical yoga practice entirely.

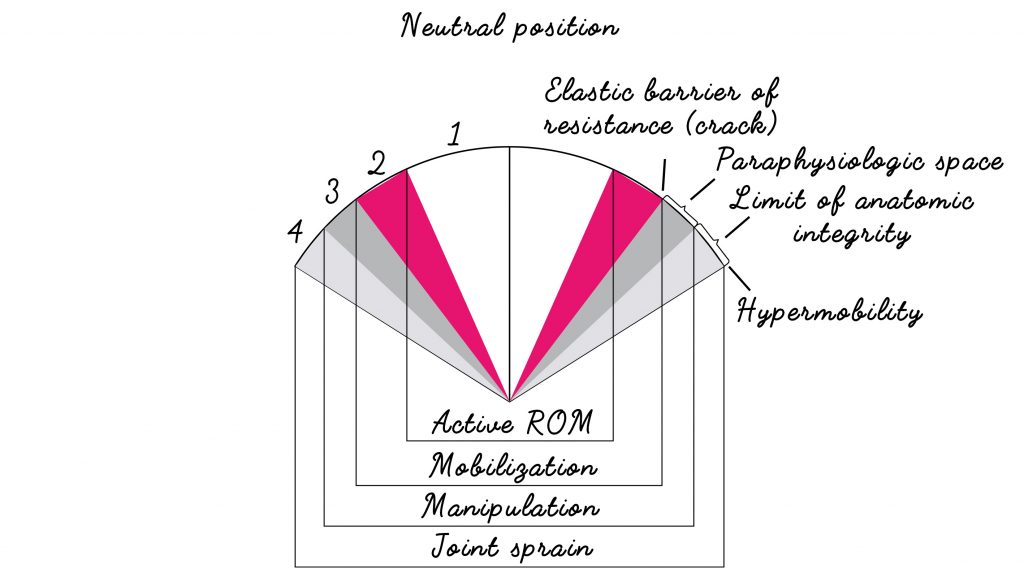

Training active range of motion is where we want to spend most of our time. Active Range of Motion represents the degrees of our movement that we have control over; our muscles are able to sustain tension, be efficient in generating power, and stabilize the surrounding joints.

Passive Range of Motion takes us to our end-ranges and the aforementioned elastic barrier. This represents the degrees of motion that we do not have control over. Your nervous system stopped you for a good reason when you were active: it doesn’t want you to compromise the integrity of your soft tissues and hurt yourself.

“Being active and physically practicing the movement is essential for neuromuscular adaptation. During active movement, the whole of the motor system is engaged. In contrast, during passive movement, there is no efferent activity or muscle recruitment… Interestingly, passive movement rarely occurs during normal activities. It can be inferred from this observation that the motor system is well accustomed to adapt to active rather than passive movement.”

-Dr. Eyal Lederman

Fancy anatomy talk summed up:

- Our classes and postures should be focused on the active components of the movement involved.

- Extending/deepening aesthetically further into a pose represents our movement potential.

- The active control we have over our motion is our movement reality.

- The gap between our movement potential (Passive Range of Motion) and our movement reality (Active Range of Motion) is the zone in which we are at a higher risk of injury. This is because we have gone beyond what we can control well.

- If our intention is to create fluid, smooth, and coordinated movement, we look at this whole system together and create Motor Control (Refer to the first part to this series!)

- Your ability to move mindfully and control your movement represents

“Having great flexibility without control is like you having a car that goes 100 mph, but brakes that only work to 60 mph. How safe is it driving that car at 100 mph?”

-Moses Bernard

Yeah. Heavy stuff. And we’ve still got more to discuss!

Tightness, Decreased Range of Motion, and Stability

Perhaps the thing we have most backwards in the way we approach the human body in yoga is the concept of “tightness.” Allow me to blow your mind and bust a few myths in this section 😉

Tightness is a perception. The peripheral nerves in your soft tissues and joints relay to your brain that an area/muscle “feels tight.”

But what is tightness really? Is the tight muscle over stretched? Or perhaps it is constricted and needs to be opened?

Most yoga teachers (and the average person on the street) would have you believe that tight muscle is constricted and the fix is to open or stretch it. This understanding is only half right…

I akin the perception of tightness to that of a rubber band. When you stretch out a rubber band, it becomes really tight, right?

The “tight” muscle is constricted, but often that’s because it’s already over stretched!

Let’s think critically about this for a moment:

- What areas/muscles are typically “tight?”

- Hamstrings, lower back, upper traps, etc

Makes a lot more sense now right?! Have you ever wondered why your perceived tightness comes back after you stretch it? You know the definition of insanity right…. Doing the same thing over and over again while expecting different results.

Stretching the tightness away isn’t the way to fix it. How do you remove the tightness of a rubber band? You allow it to return to its normal state. The proper fix (*Disclaimer* for most but not all people) is to strengthen the area that feels tight!

I hope you can use this shift in perspective of tightness to empower your practice. Approach the tight muscle from the realm of strength, rather than stretch, and your perceived tightness may fade away.

[Disclaimer: To avoid future confusion I’ll be using tightness and constriction together to describe decreased range of motion throughout the rest of this article. While technically different, the two terms do describe the perception of a decreased range of motion (tightness potentially representing over-stretched tissue vs constriction being more vague and representing “chunky,” “limited,” etc)]

Now that we’ve covered the logic of our approach to tightness, the larger question is still:

Why does our body perceive tightness and constriction?

Have you ever wondered why your body tightens and constricts to limit your range of motion?

The answer is quite simple: Safety first.

“A lack of mobility is a nervous system spot weld for stability”

-Dr. Perry Nickelston

Your nervous system hinders your movement potential in an effort to keep you safe. It tightens and constricts your soft tissue in an effort to create tension. Tension = stability.

Here’s a cool thought experiment: Is tightness and limited range of motion dysfunctional or functional?

The first time this question was presented to me I thought the same thing as you’re likely thinking right now: Limited ROM is dysfunctional. Turns out we are pretty wrong. It’s HIGHLY functional, in that our body and nervous system are doing one of their primary functions: avoiding pain and damage even if that means limiting our movement to accomplish it.

So what do we do in yoga about decreased ROM and tightness? Stretch and open the afflicted anatomy.

We think that limited ROM is a flexibility issue, and the common solution to increase flexibility is stretching. This is foolish because we’re taking away from what our nervous system did naturally and functionally, without ever addressing the real issue: what isn’t feeling safe/stable that resulted in that feeling of tightness/constriction in the first place.

“Muscle tightness is not caused only by biomechanical properties, but as a strategy or compensation to maintain equilibrium during movement”

“Calling all limited motion problems a flexibility issue is problematic in that it imparts the assumption that all can be helped with stretching”

-Gray Cook

[Extremely Important Disclaimer: Every body is different. What I mentioned above applies to many folks, but that still does not mean it accurately addresses what YOU feel. The best approach is to find a professional who can give you a proper assessment and diagnosis to address YOUR individual needs. However, if you’re a yoga teacher, remember that having this information does not mean you can give medical advice in regard to pain and tightness. Operate within your scope of practice, work with and refer to a professional; that’s seriously the best way to help your student (or your own body).]

Stability:

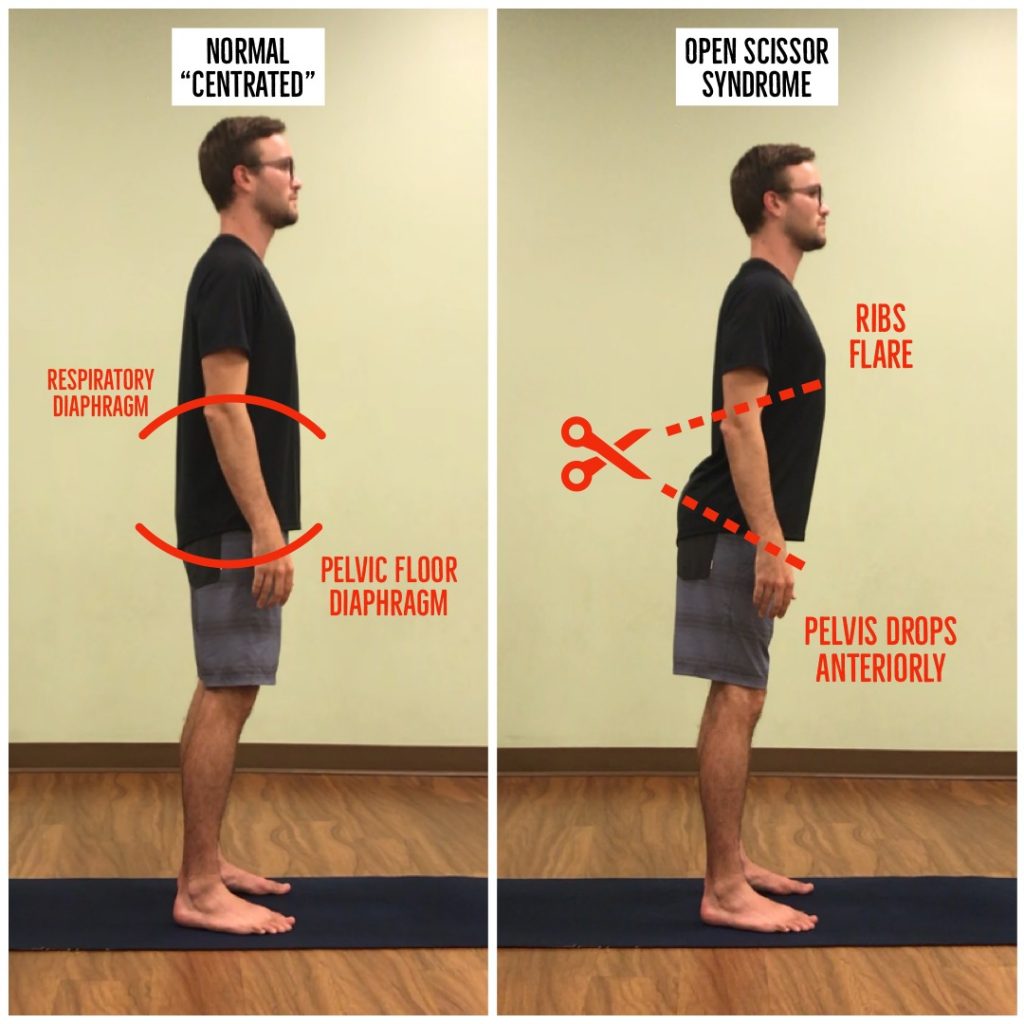

Stability is often defined as our ability to control our movement and prevent unwanted movement. Every joint has a property of being stable, while also maintaining a degree of mobility.

Note that every joint is mobi-stable (has a degree of stability and mobility). This chart represents the preferences of each joint based on their range of motion and morphology.

An easy way to think about stability is that in order for one part of your body to move, another part has to maintain a degree of not moving to allow the moving part to move.

Terminology for the body nerds:

- Support – Joint/area not moving

- Phasic – Joint/area moving

Reflection Moment: Under the lens of Support and Phasic, think about how you transition between yoga poses. With each transition, what body part is supporting you? What body part is moving? How might this influence the way you perceive your movement (or, for the teachers, how you cue the movement)?

In kinesiology, we have a saying: “Proximal stability creates distal mobility.” Translated into normal people speak: Creating spinal and core stability allows for better movement from your limbs.

Centrating and Positioning

Tension

Okay, back to limited ROM. There are a million ways to release tension and increase your ROM. For example, stretching, joint mobilization, breathing, massage, rolling on therapy balls, and so on. Which one is right? You tell me; what you like the most is often the best answer. (If you’re not sure, then definitely book an appointment with a manual therapist as they’ll likely be able to give you an assessment and guide you properly).

Once you release tension, you have a very important next step: put tension back in!

Tension = stability.

If you release tension in one spot you must increase tension in another.

Just like with releasing tension, there’s no one method to increase tension fits all to this approach. I hope I can supply you with the tools to think critically and employ this concept effectively.

The basis of increasing tension is strength. Applying a degree of integrity, control, and resistance (*cough* active range of motion *end cough*) is one of the easiest ways.

Here are some ways to increase tension in a region:

- Integrity and Control:

- Approach the movement at a slower pace (I like the cue: “move at 1 mph” or, for everyone not in the U.S., “move at 1 kilometer per hour”)

- Upholding good form and observing when your body tries to compensate

- Resistance

- Moving as if the air were thicker

- External resistance: weights, resistance bands, etc.

- Irradiating tension (see below).

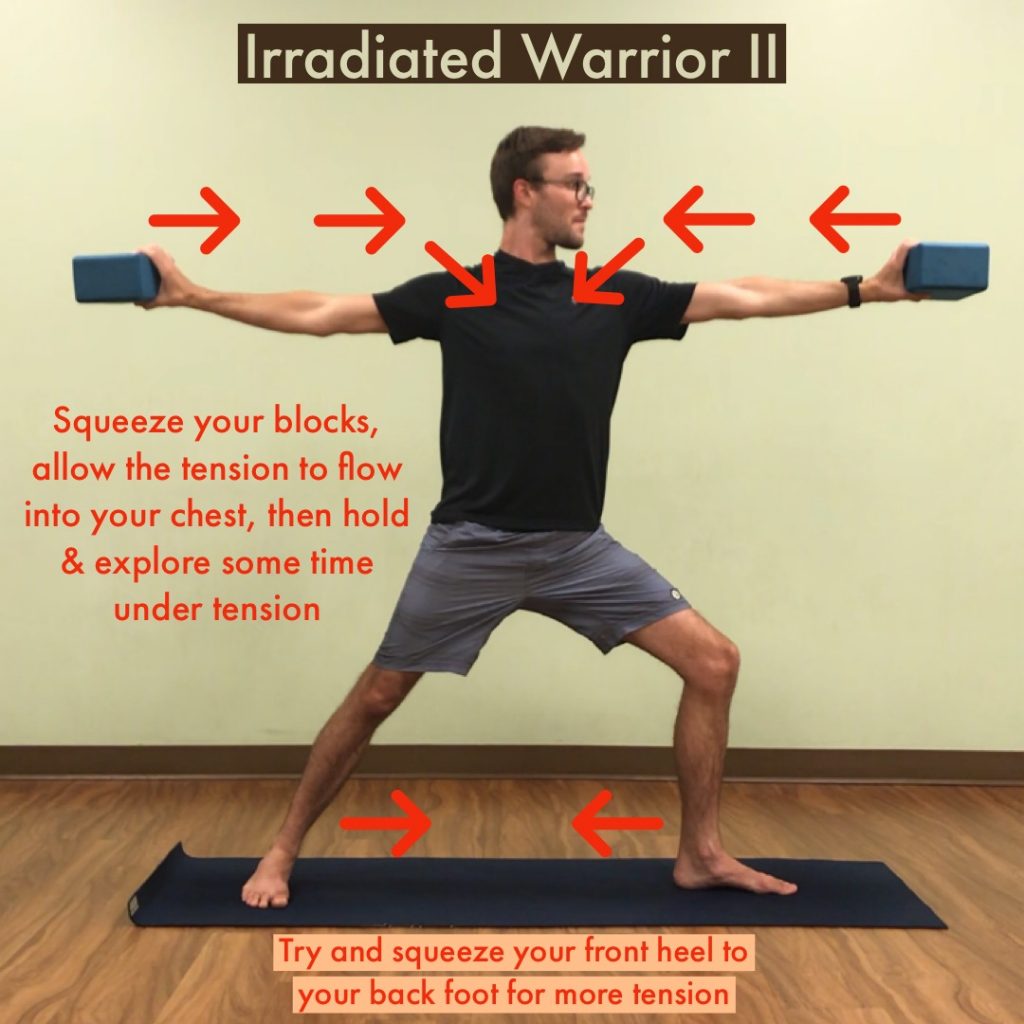

Sherrington’s Law of Irradiation:

This biomechanical principle refers to tensing up one area of your body intensely to irradiate that tension into other related areas

Example 1: Fists & Blocks

1) Squeeze your fist a little bit. Notice where you feel it (likely local to your fist)

2) Squeeze your fist more and notice as the tension begins to move up your arm through your biceps and triceps

3) Squeeze your fist as much as you can and now notice the tension flow into your chest

Example 3: Irradiated Warrior II

1)Squeeze your blocks as much as you can and feel the tension flow through the arms to your chest.

2) Connect that tension through your core with your legs by attempting to squeeze your legs together

3) Hold or explore slow movements (like rotating your arms or moving into other postures like Side Angle & Reverse Warrior)

Example 3: Corkscrew Feet & Hands

When you approach your asana with the active range of motion in mind, you’re practicing all of these. Operating within your movement reality creates the right systematic firing and impulses that uphold a level of mobility and stability.

Section Summary:

- Tightness is often a perception of over-stretched tissue

- Our nervous system limits our range of motion in a functional effort to keep us from harm

- Limited Range of Motion is an overabundance of stability

- Stability is our ability to prevent and control our movement

- If you release tension (using whatever method you please), you have a responsibility to put some tension back in.

Side note #1: What about Yin Yoga?

After reading all this, I’m sure some of my Yin yogis are wondering what does all this mean in regard to Yin. Honestly, take a look at Bernie Clark’s work. His blog and his books Your Body, Your Yoga and Your Spine, Your Yoga perfectly address this question. I don’t have a full understanding of Yin yoga or a full familiarity with its practice, but from my current understanding here’s *my opinion*: Remember to dial it back. Yin should happen right at the border of active and passive ROM, NOT at the elastic border. Support yourself properly and actively reverse out of each posture (rather than slump out of a passively held pose).

I’ll elaborate a little more on this topic in the next article when I talk about how our body remodels and biomechanical creep.

Side note #2: Hypermobility

Hypermobility is actually a bit of a misnomer. Based on what you just learned in this section think critically at what hypermobility suggests: An excess of mobility. That’s a pretty good thing! We want to be really mobile; it’s an excess of flexibility that makes things go awry.

Better deemed “Hyper-flexibility” is a massive topic on its own. When we flip the terms and look critically, hyper-flexibility suggests the individual has a larger degree of Passive Range of Motion. What this does not infer is a larger degree of Active Range of Motion.

There is a spectrum to Hyper-flexibility, and it can result from a variety of factors: genetics, SAID principle, athletic sports, conditioning during youth, puberty, pregnancy (yay elastin!), etc.

Regardless of the cause, what is often the case with hyper-flexible folks is a large PROM (movement potential) and an often terrible AROM (movement reality). What many hyper-flexible folks will attest to is the need for strength training and active control.

That’s the beauty of active range of motion in yoga. Every body benefits from it. Everyone can work on their AROM because it’s very individually based and therefore accessible to everyone. It’s also fun because it forces us to accept the limits of our control over our movement and stay humble on the path to body bliss.

Promoting Passive Range promotes ego. The inflexible folks look and compare themselves to the flexy-bendys and think that’s the goal of asana. Meanwhile, those flexy-bendys are over-stretching themselves into a potential life of chronic pain.

Don’t believe me? Need more? Take a look at any chronic hypermobility forum. They are filled with stories of “I wish I knew I needed to strengthen my body and not just lengthen it” stories.

Further Sources:

- Living with joint hypermobility syndrome: patient experiences of diagnosis, referral and self-care

- Fran’s story: Living with hypermobility syndrome: it might not kill you but it can take your life away

- Facebook Group: Yoga for those with Hypermobility & Ehlers-Danlos

My intention is to always promote movement positivity. If you like stretching, keep stretching. Just remember you need to strengthen, especially if you stretch regularly.

Mobility vs. Flexibility

I jokingly say, “Flexibility is the new F-word.” Mobility is the new flexibility in that increasing your mobility is a preferable objective to have with your body.

Let’s examine the parts of each.

Flexibility:

- The ability of a muscle or muscle group to lengthen passively

- Range of motion you may, or may not, have control over

- Flexibility does not carry over to general movements (walking, running, gardening, & other daily activities)

Mobility:

- The ability of a joint to move actively through a range of motion

- Range of motion you have active control over

- Mobility carries over to general movements

Flexibility is not worthless; it is the prerequisite for mobility. Another way to contextualize this relationship is Mobility = Usable Flexibility

Mobility is more holistic; it embodies strength, coordination, flexibility, core, and balance. It allows to perform a movement with a sense of ease and fluidity.

“A person with great flexibility may not have the core strength, balance, or coordination to perform the same functional movements as the person with great mobility.”

-Unknown

Active Tree Pose vs. Passive Tree Pose

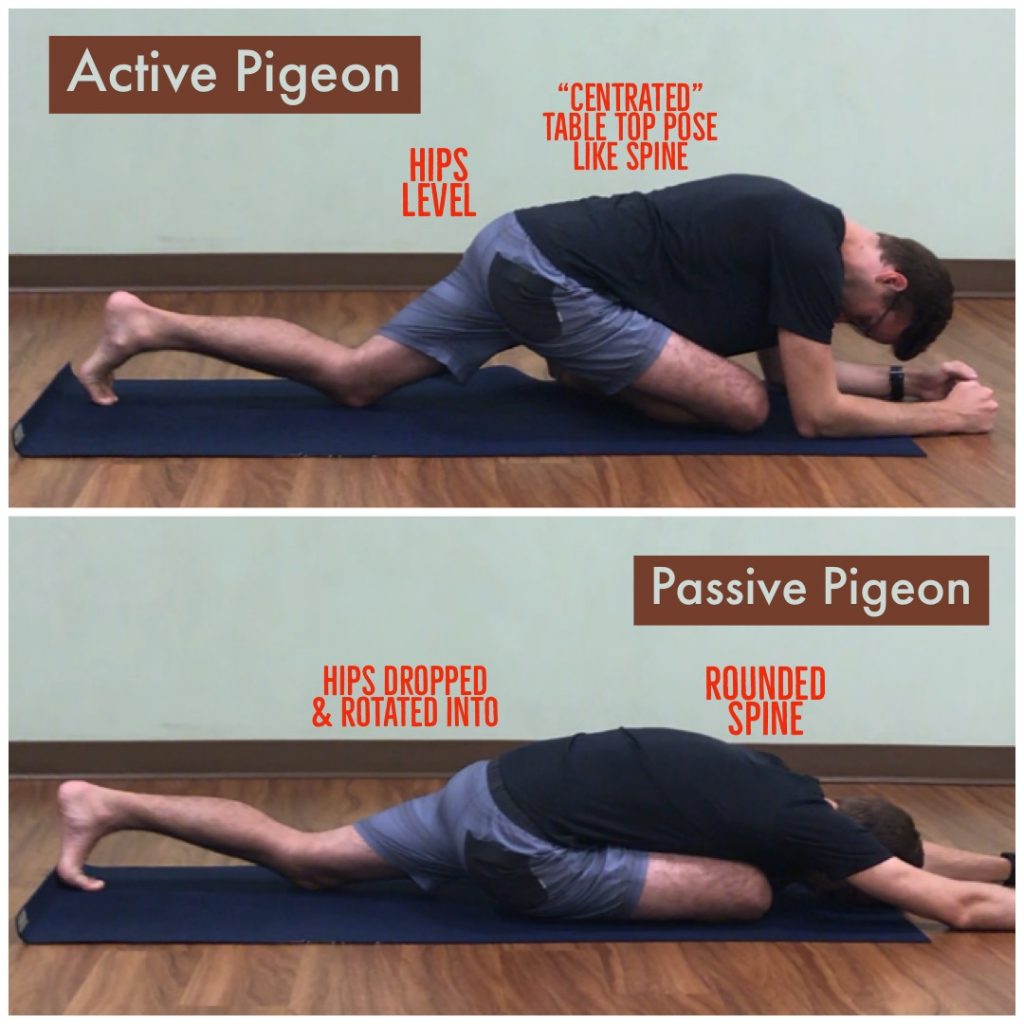

Active vs. Passive Pigeon Pose

Active vs. Passive Lunges

Conclusion:

We have now hit the end and stretched our noggins to a higher level. I believe the information presented here should be the standard taught to every yoga teacher. In asana, we deal with the Range of Motion on a daily basis, and yet what we’re traditionally taught does not match up with current views in the scientific world.

Many of us who are a part of the movement towards practicing safety & sustainability in yoga asana like to jokingly use the hashtag #passiveispassé. It represents how the aesthetic depth & ROM sought in older practices of yoga asana are out of date. My hope is that I’ve shown you the value to practice more active movement but also did not deter you from doing the things you like (including more passive & stretch based exercises). We want to do Yoga & move our entire lives right? My advice: explore active range of motion more than you explore passive range of motion. All movement is good movement.

Range of motion is a nervous system experience. It allows us to see our movement potential via our flexibility and yet gives us an approach to accept our current reality via our mobility. It can serve as an opportunity to embark on a moving meditation and another reminder on our yogic paths to remain humble and honest with ourselves as we continue to observe and accept our minds and bodies.

When you reflect and refer to what was presented here, look at the way you approach your yoga poses and daily movements. Explore each concept of mobility, stability, tension, and the like with the mind of a scientist: What happens when I do this? Observe your body’s reaction to each experiment and act accordingly: oh that didn’t feel good – I’m not going to do that again. Or, what can I change to make this feel better?

You just learned a few important concepts, and I hope this information empowers what you already know and fosters you into a new understanding of your own anatomy.

With this information, I implore you to go back to the previous installments of this Your Brain on Yoga series and see how each of these parts interplay with one another.

- Part I: Motor Control – How you cue (internal vs. external) can have a direct impact on the mobility expressed by your joints. Moving internally = less whereas moving externally (goal-oriented) can create a lot more active range of motion.

- Part II: Proprioception – Stimulation of your nervous system can help release and activate muscles & tissue. It can also directly impact your ROM and how you perceive your mobility. Creating a safe environment can also help people open up their ROM vs. their nervous system feeling threatened and restricting their ROM

The final installment of our neuroscience journey will be about how our body changes in relation to the feedback we give our nervous system. Our movements create physical changes in our body over time, and it’s incredibly valuable to understand how this interplays with the way we practice over time. Stay tuned for Part IV: Adaptation, Remodeling, and Sequencing.

-Dr. YG

Read Your Brain on Yoga. Part I: Motor Control

Read Your Brain on Yoga. Part II: Proprioception

Illustrations by Ksenia Sapunkova

Edited by Sarah Dittmore